Chinese President Xi Jinping is set to unveil a $46 billion infrastructure spending plan in Pakistan that is a centerpiece of Beijing’s ambitions to open new trade and transport routes across Asia and challenge the U.S. as the dominant regional power.

Chinese President Xi Jinping is set to unveil a $46 billion infrastructure spending plan in Pakistan that is a centerpiece of Beijing’s ambitions to open new trade and transport routes across Asia and challenge the U.S. as the dominant regional power.

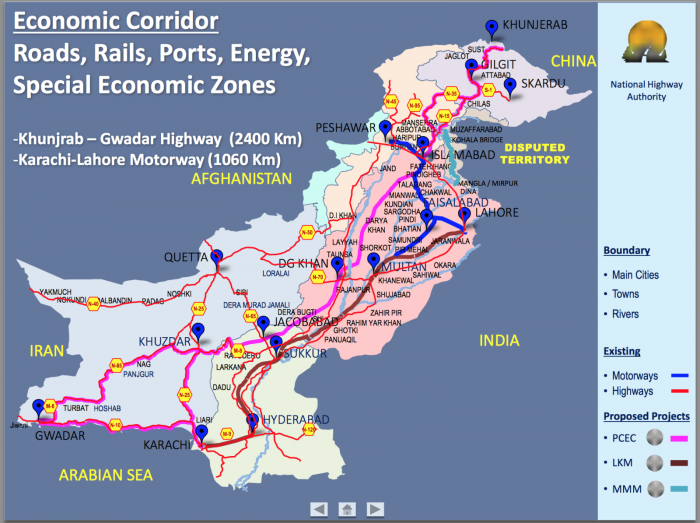

The plan, known as the China Pakistan Economic Corridor, draws on a newly expansive Chinese foreign policy and pressing economic and security concerns at home for Mr. Xi, who is expected to arrive in Pakistan on Monday. Many details had yet to be announced publicly.

“This is going to be a game-changer for Pakistan,” said Ahsan Iqbal, Pakistan’s planning minister, who said his country could link China with markets in Central Asia and South Asia.

“If we become the bridge between these three engines of growth, we will be able to carve out a large economic bloc of about 3 billion living in this part of the world…nearly half the planet.”

Beijing’s primary concern is that instability in neighboring Pakistan and Afghanistan is spilling into China’s predominantly Muslim northwest, and could grow worse with the withdrawal of U.S. troops from the region.

China sees a historic opportunity to redraw the geopolitical map by succeeding where the U.S. has largely failed, building critical infrastructure that could kick-start economic growth and open new trade routes between China and Central and South Asia. A cornerstone of the project will be to develop the Pakistani port of Gwadar, a warm-water port run by the Chinese on the doorstep of the Middle East.

If realized, the plan would be China’s biggest splurge on economic development in another country to date. It aims over 15 years to create a 2,000-mile economic corridor between Gwadar and northwest China, with roads, rail links and pipelines crossing Pakistan.

The network ultimately will link to other countries as well, potentially creating a regional trading boom, Pakistani and Chinese officials say.

The Pakistan program has been described by Chinese officials as the “flagship project” of a broader policy, “One Belt, One Road,” which seeks to physically connect China to its markets in Asia, Europe and beyond.

“If ‘One Belt, One Road’ is like a symphony involving and benefiting every country, then construction of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor is the sweet melody of the symphony’s first movement,” Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister said during a visit to Pakistan in February.

Terrorism-plagued Pakistan is a risky bet for Beijing, however. During the Chinese president’s coming visit, Islamabad is set to announce that it will raise a special security force of thousands to protect the Chinese workers and engineers who will flood into Pakistan to carry out the work alongside locals, Pakistani officials said.

The largest part of the project would provide electricity to energy-starved Pakistan, based mostly on building new coal-fired power plants. The country is beset by hours of daily scheduled power cuts because of a lack of supply, shutting down industry and making life miserable in homes—a major reason for the election in 2013 of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, who promised to solve the electricity crisis.

The plans envisage adding 10,400 megawatts of electricity at a cost of $15.5 billion by 2018. If those projects deliver, plugging the electricity deficit, Mr. Sharif would be able to go into the 2018 election saying he has lived up to his pledge.

After 2018, adding a further 6,600 megawatts is outlined—at a cost of an additional $18.3 billion—that in cumulative total would double Pakistan’s current electricity output.

The plan has gained political momentum—and new funding sources—since Mr. Xi outlined his vision to build modern-day equivalents of the ancient Silk Road between East and West.

Despite the more-muscular Chinese ambitions, U.S. officials say the new economic strategy complements Washington’s vision for the region.

“We think there’s a great amount of potential complementarity between a China-Pakistan infrastructure corridor and the interests we’ve talked about in South and Central Asia for some time,” said a State Department official. The U.S. and China “have coincident interests in seeing a stable, peaceful and prosperous Pakistan.”

Still, Beijing’s plan would dwarf the multibillion-dollar U.S. assistance program in recent years for Pakistan. Under the 2009 Kerry-Lugar-Berman Act, the U.S. poured more than $5 billion in aid to Pakistan between 2010 and 2014, including $2 billion on infrastructure, some of which is still being spent. In the energy sector, the U.S. program is adding some 1,500 megawatts of generating capacity.

Unlike the U.S. approach of giving traditional development aid, which some say has yielded only incremental improvements to Pakistani infrastructure, most of the Chinese money would be spent on a commercial basis, through investments or loans.

Andrew Small, author of “The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics,” said China was reacting to the perceived failure of Western aid to make a significant difference to Pakistan. “The Chinese response is that you haven’t done it on a large enough scale,” Mr. Small said. “They’re saying that it is only by doing it on this kind of big-bang scale that you’re going to have the transformative economic effect that Pakistan needs.”

Gwadar, operated by a state-run Chinese firm, is set to begin commercial operations this year, and one of the deals to be signed by the Chinese president while in Pakistan is a final agreement on building a new international airport there, Pakistani officials said.

Mr. Small said propping up Pakistan economically furthers China’s regional competition with India. China sees Pakistan as a strategic counterweight to India. Conversely, the U.S. is backing India, which President Barack Obama visited in January, as a counterweight to China, despite Washington’s long relationship with Islamabad.

The U.S. aid program in Pakistan is winding down, while American forces have largely pulled out of Afghanistan, where China is trying to initiate peace talks between Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s government in Kabul and the Taliban insurgents.

Beijing fears that without its intervention, chaos, extremism and economic stagnation in Pakistan and Afghanistan will blow across into its bordering northwestern region of Xinjiang, which has a large Muslim population. China has grown increasingly concerned in the past two years about an surge in jihadist and separatist violence in Xinjiang.

Northwest China is far from the Chinese coast, and shipping goods to and from there through Pakistan would potentially be quicker and cheaper than using any Chinese port, cutting costs and time in half, according to Pakistani calculations.

Beyond the economics of the Pakistan corridor are strategic advantages: China is concerned that too much of its trade depends on the narrow sea channel of the Strait of Malacca, analysts said. In the event of a future war in Asia, the Strait of Malacca could be blockaded by the U.S. Navy or another competing power. Pakistan would provide an alternative land route for Chinese trade.

During his visit, Mr. Xi will sign off on billions of dollars worth of the more-advanced projects in the corridor project, allowing the start of groundwork, Pakistani officials said. In addition the economic corridor framework, more than $10 billion in other new Chinese infrastructure projects for Pakistan are in the works.

Frederick Starr, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and an expert on Central Asia, said the new corridor has potential to link Europe to China through Central Asia and the Caucasus, and reach onward through Pakistan and India to Southeast Asia, a route that he said “will in 30 years be more important even than China’s [current] route to the West.”

WSJ

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.