At first glance, Iraq’s second city of Mosul looks like a model of success for its new rulers from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Isis), the world’s most feared jihadi group. Well-swept thoroughfares bustle with cars, the electricity hums and the cafés are crowded.

But in the back alleys, litter fills the streets. The lights stay on, but only because locals rigged up generators themselves. And under the blare of café televisions, old men grumble about life under Isis’s self-proclaimed caliphate.

“When I was seven years old the war against Iran started. Since then, we’ve been at war,” says Abu Ahmed, a quiet 40-year-old with a long grey moustache. “We’ve endured international sanctions, poverty, injustice. But it was never worse than it is now.”

Like those of others interviewed for this article, the name of Abu Ahmed, an honorific, was changed for his safety.

Abu Ahmed at first welcomed the takeover by Isis, which seized more than a quarter of Iraq and Syria this summer. He was not alone: Sunni Muslims in both countries have long felt discriminated against by regimes dominated by rival sects — in Baghdad, Iraq’s Shia majority; in Damascus, the minority Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shia Islam.

Isis supporters have tolerated everything from public stonings and beheadings to daily air strikes by the US-led coalition. But without an economy that gives people a chance to make a living, many say Isis has little more to offer than the authorities they replaced.

“Compared to past rulers, Isis is a lot easier to deal with. Just don’t piss them off and they leave you alone,” says Mohammed, a trader from Mosul. “If they could only maintain services — then people would support them until the last second.”

On that critical measure, locals say, Isis is losing its lustre: to traverse the ostensibly unified “caliphate,” a traveller needs three different currencies; aid groups provide medicine to much of the area; and salaries are often actually paid by Iraq and Syria — governments with which Isis is at war.

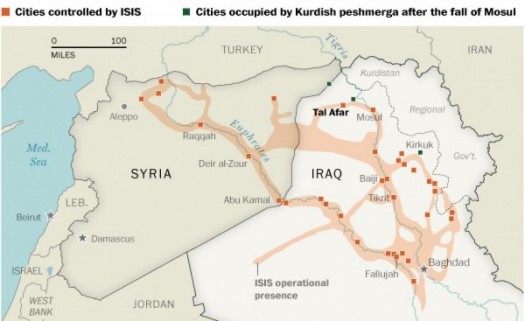

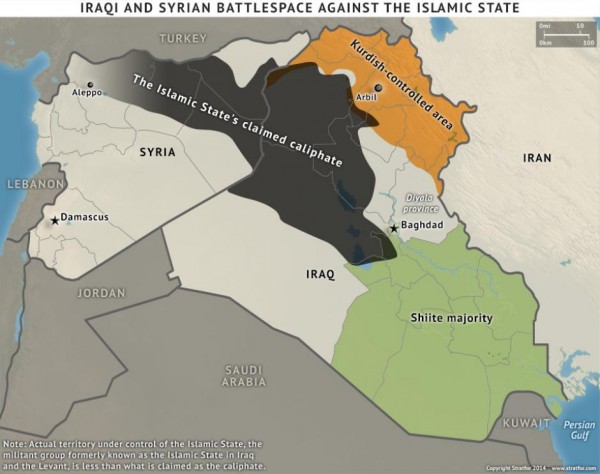

Chart the progress of the jihadi militants as they attempt to gain more ground

Rather than take over the reins of state, Isis is often contributing to its dysfunction by engaging in extortion rackets.

“In the Syrian cities of Raqqa and Deir Ezzor they may be functioning something like a state, but there’s nowhere in Iraq where they’re operating anything like a state,” says Kirk Sowell, president of Uticensis Risk Services. “They’re operating like something between a mafia, an insurgency and a terror group. Maybe they thought six months ago they were going to function as a state. But they don’t have the personnel or manpower.”

Isis’s repression and restrictions on media make it difficult to fully portray the group’s administration system, but through a series of more than a dozen interviews with residents, and visits to Isis-ruled areas by a local journalist, the FT found its attempt at state-building has so far failed to win over locals.

In some cases they say Isis takes credit for systems in place before it seized power. In others, locals say it is stealing the resources of the region it seeks to rule.

Last June, Isis fighters bulldozed Syrian-Iraqi border posts and declared “the end of Sykes-Picot”, the agreement that divided the Middle East between French and British control. The group posted videos of volunteers handing out sacks of wheat stamped with their black and white seal. They even announced plans to issue a currency, posting a design for a new gold dinar on Mosul’s streets and handing out pamphlets in Raqqa, in Syria’s north.

From the outside, these projects look impressive — especially to people living in chaos in northern Syria, where rival rebel groups trying to topple President Bashar al-Assad’s government have been at war and unable to impose order.

Yet for those travelling the bumpy dirt road between Mosul and Raqqa, the borders have not changed, even if Isis reduced the crossings to rubble. Travellers must stock up on Iraqi dinars to use in Iraq, US dollars for the road and Syrian pounds once they arrive.

It is as if Isis is financing itself partly through a pyramid scheme, and this has begun to falter

Tweet this quote

If Isis’s “caliphate” were a state, it would be a country of the poor. Most Syrians in the territory are struggling to get by on about $115 a month. Isis’s foreign fighters make as much as five times that. In Syria, the price of bread has nearly doubled to almost a dollar — about a third of the daily income for Syrian civilians. Even though Mosul was cut off from Iraq’s power grid when Isis took the city this summer, the electricity stayed on. But this is mostly thanks to the efforts of locals, who bought and set up generators to keep the power running in their neighbourhoods.

In Isis-controlled Syria, electricity still functions a few hours a day — courtesy of Mr Assad’s regime. Mahmoud, an engineer, and his colleagues still file into the same power plants where they worked for years before Isis took over. But while the militant group’s oil and gas authority now oversees them, the Damascus government still pays their wages. Thousands of civil servants have similar arrangements in Isis-controlled Syria and Iraq, where locals risk long and dangerous drives to pick up their pay in Baghdad.

Isis seized control of three dams and at least two gas plants in Syria used to run state electricity. Rather than risk blowing out swaths of the power grid, Damascus appears to have struck a deal.

“Isis guards their factories and lets state employees come to work,” Mahmoud says. “It gets to take all the gas produced for cooking and petrol and sell it. The regime gets the gas needed to power the electrical system, and also sends some electricity to Isis areas.”

Not only does the Assad government pay the gas plant staff, but workers say it sends in spare parts from abroad and dispatches its own specialists to the area for repairs. “I’m against Isis with all my heart,” Mahmoud says. “But I can’t help but admire their cleverness.”

Sajad Jiyad, an independent researcher in Iraq, says that Isis struggles to balance its books, but services continue to function because of the money Baghdad still pays to former civil servants in Mosul. Isis taxes those employees at up to 50 per cent of their salaries.

“Isis is dependent on its ability to seize territory and resources to continue funding its existing areas,” he says. “Its expansion is sometimes operated through affiliates who use the Isis brand but are in effect local mercenaries. It is as if Isis is financing itself partly through a pyramid scheme, and this has begun to falter.”

Basic services function poorly, but fear prevents anyone from speaking out. “Electricity, fuel, medicine, water are in low supply but people are surviving,” he says.

When they (Isis) are not there, we charge a higher price. Locals understand. The prices can’t always be what Isis says

Though many now question Isis’s economic management, its military prowess and organisational skills are clear. Despite the coalition’s strikes, which have stalled its advances, Isis holds huge stretches of territory that encompass up to a third of Iraq and a quarter of Syria.

Some of the group’s policies are seen as better than the previous regimes. Isis allows easy movement through its territories to facilitate trade. Trucks passing through are taxed about 10 per cent of the value of their cargo. Some businessmen in Iraq’s northern Kurdistan region, who drive shipments through the group’s territory, see the scheme as “Isis’s business-friendly face”.

It is also relatively easy to start a business — there are no start-up fees for those who want to open a store, though they have to pay a 2.5 per cent tax on their revenue after each year.

But to locals, these policies produce little benefit. There are few business opportunities in a conflict zone where people are scraping by, usually with help from relatives who fled abroad.

In Syria’s eastern Deir Ezzor province, home to most of Syria’s oil wells, locals also complain about Isis commandeering their resources. “If they don’t take it, they tax you for it,” jokes the gas engineer Mahmoud. Isis, which he estimates controls nearly 40,000 barrels a day of oil production in eastern Syria, is believed to be the richest militant group in history, making perhaps $1m a day on oil and extortion rackets.

The coalition has been trying to bomb makeshift oil refineries to hurt Isis’s finances, but locals say that has little impact. Isis makes the bulk of its money from selling crude from the oil wells to Turkish, Iraqi and Syrian middlemen. Local partners refine the oil and sell it.

But other than these traders, most residents say they see little of that oil wealth.

Bassem, a hospital worker in Deir Ezzor, says when civil war first spread to eastern Syria two years ago, the region went from an impoverished backwater to a boomtown as rebels and tribes took control of oil wealth previously extracted and used by the regime. “You saw fancy cars, new stores. People were doing really well,” he says, speaking to the FT via Skype.

But under Isis, economic conditions steadily worsened, he says: “There’s no ‘economic administration’ with Isis — there is only people who take oil, divide it between the emirs and send it out. Where? We don’t know. Only a very tiny portion comes back to the people.”

Isis has tried to shape itself as a just ruler by setting prices on everything from bread to caesarean sections, which go for about $84. But locals routinely ignore the caps, Bassem says, because such prices are impossible to maintain given the skyrocketing costs of fuel and transportation. “Isis doesn’t study the market, it doesn’t calculate costs . . . these price caps are just comical.”

As a conservative Salafi Muslim, he was sympathetic to Isis’s ideology when they first took over, but was quickly disillusioned as economic conditions worsened. “I may be a Salafi, but I’m not an idiot,” he jokes.

Bassem’s hospital works round the price caps by charging patients for everything from the electricity to drugs. “When they [Isis] are not there, we charge a higher price,” he says. “Locals understand. The prices are not always what Isis says, because they can’t be.”

International aid groups often send in medicines and supplies, which Isis tolerates out of necessity. Iraqis see the practice in Mosul hospitals, too.

While it is impossible to know how deeply the frustration with Isis policies runs — as some are undoubtedly benefiting from them — all those interviewed say signs of discontent were rising.

When Isis members recently came to collect taxes for electricity in Raqqa, a car mechanic became so enraged he shouted as they approached his garage: “How can you ask for fees on a service only available a few hours a day?”

Further east, at a mosque in Syria’s city of Meyadeen, a former activist who once organised anti-Assad protests says he witnessed an eerily familiar scene. After Friday prayers, an imam mimicked a practice common in the era of Assad control, when congregants were made to pray for their president. This time, they were told to pray for Isis’s leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

From the back of the room came faint but audible whispers: “Screw him.”

Financial Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.