The Islamic State, which now controls an area of Iraq and Syria larger than Britain, may be raising more than $2 million dollars a day in revenue from oil sales, extortion, taxes and smuggling, according to U.S. intelligence officials and anti- terrorism finance experts.

Unlike other extremist groups’ reliance on foreign donations that can be squeezed by sanctions, diplomacy and law enforcement, the Islamic State’s predominantly local revenue stream poses a unique challenge to governments seeking to halt its advance and undermine its ability to launch terrorist attacks that in time might be aimed at the United States and Europe.

“The Islamic State is probably the wealthiest terrorist group we’ve ever known,” said Matthew Levitt, a former U.S. Treasury terrorism and financial intelligence official who now is director of the counterterrorism and intelligence program at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “They’re not as integrated with the international financial system, and therefore not as vulnerable” to sanctions, anti-money laundering laws and banking regulations.

In contrast, the late al-Qaida chief Osama bin Laden was from a wealthy family and enjoyed a network of foreign patrons, and his funding sources were squeezed by financial intelligence officers. The Islamic State “makes their money primarily — if not entirely — locally,” said Patrick Johnston, a counterterrorism specialist at the Santa Monica, Calif.- based RAND Corp.’s Pittsburgh office and co-author of a forthcoming analysis of declassified documents on the Islamic State’s finances.

The money that the Islamic State group receives from outside donors pales in comparison to its income from extortion, kidnapping, robbery, oil smuggling and the like, said a U.S. intelligence official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss classified information.

While al-Qaida and other groups which the U.S. designates as terrorists, such as Hezbollah, Hamas and various Palestinian and other groups, have long depended largely on the kindness of sympathizers and state sponsors such as Libya and Iran, some self-financing by militant groups isn’t new.

The Afghan Taliban smuggle opium, minerals and timber; Colombia’s Marxist FARC rebels export cocaine; and Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines, as well as the al-Qaida offshoots in Yemen and North Africa, have raised millions by taking hostages for ransom.

There are few reliable financial figures for the groups. A U.N. report estimated the Taliban raised about $400 million in 2011 through local taxes, donations, and extortion directed at drug smugglers, mobile phone operators and aid projects.

The revenue streams available to the Islamic State through its control of a vast oil-rich territory and access to local taxes dwarfs the income of other groups.

SELLING CRUDE OIL

With its control of seven oil fields and two refineries in northern Iraq, and six out of 10 oil fields in eastern Syria, the terror group is selling crude at between $25 and $60 a barrel, Luay al-Khatteeb, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Doha Center in Qatar, said in a telephone interview. That reflects a discount from world market prices due to the risk faced by middlemen smuggling and brokering the oil. By comparison, Brent crude for October settlement fell 1 cent today to $102.28 a barrel on the London-based ICE Futures Europe exchange.

Based on al-Khatteeb’s interviews with contacts in Iraq, the extremist group controls Iraqi fields with a production capacity of 80,000 barrels a day and now is extracting about half that amount. The Islamic State, he said, is likely earning some $2 million a day from crude sales, paid in cash or bartered goods as the oil crosses into the Kurdistan region of Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Jordan.

One important financial battlefield for the Islamic State, said the U.S. intelligence official, is the Baiji refinery in northern Iraq, which produces roughly a third of the country’s total oil output. It’s been shut down since an attack by extremists in June, and remains the scene of heavy fighting between extremists and government forces.

The extremists’ oil income is going to “keep the war machine running, to maintain institutions” in the territory the Islamic State has seized from the Iraqi and Syrian governments, and “the rest of the cash is going to recruiting,” al-Khatteeb said.

Robin Mills of Dubai-based Manaar Energy Consulting and Project Management, said in a telephone interview that authorities have begun cracking down on oil smuggling into the Kurdish region, meaning more of the crude will be used locally by the Islamic State and oil revenues will start to shrink.

A second source of revenue for the Islamic State is taxing residents of the densely-populated cities such as Mosul in the territory it controls, which is roughly the size of Wyoming, and controlling granaries and other critical resources. Criminal activity from bank and jewelry store robberies, extortion, smuggling and kidnapping for ransom is also an important source of revenue.

The group may have raised $10 million or more in recent years from ransom payments alone, said one U.S. official.

SUBHEAD

Still, Brian Fishman, a research fellow with the Washington-based New America Foundation, a policy research organization, and many U.S. intelligence analysts, are skeptical of the oft-quoted figure of $2 billion controlled by the Islamic State.

Similarly, initial estimates immediately after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks putting al-Qaida’s wealth in the hundreds of millions of dollars greatly exaggerated the amount of money bin Laden had at his disposal, according to later reports by the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, also known as the 9/11 Commission. The CIA estimates that it cost al-Qaida about $30 million per year to sustain its activities before 9/11, an amount raised almost entirely through donations, according to a commission staff report.

The 9/11 attacks cost only $1 million, so even if the Islamic State has a fraction of the purported $2 billion — and if it can continue to earn $1 million to $2 million a day from black market oil sales — that’s still a lot of money.

The Islamic State’s “power is tied to the territories and resources they control and the population they extort money from,” Fishman said in an interview. “That suggests this organization is going to be very resilient and it’s going to take a long time to crunch them.”

Johnston said that a 2010 RAND Corp. analysis of financial records seized by the U.S. military from al-Qaida in Iraq, the precursor to the Islamic State, found a direct correlation between funding and terrorist operations.

“Cutting off financing makes them think about which attacks to do, what risks to take, and can we really afford to administer all of this territory as the Islamic State?” Johnston said.

The resources flowing into the group’s coffers now tend to move out the door in the form of payments fairly quickly, agreed the U.S. intelligence official. Still, while IS may now be the wealthiest terrorist group on the planet, war-fighting and administering territory is expensive, the official said, and although the Islamic State is flush with cash now, a key question is how sustainable its self-financing will be.

Indeed, the flip side of controlling territory that isn’t self-sufficient is that the group will be expected to pay for food, salaries, infrastructure and other services.

“That’s the tension here,” Fishman said. “Presumably, the Islamic State has an obligation to use that money for governing, for paying people to clean the streets,” and that adds to the burden of paying for recruits and terrorist operations.

Although alarm bells have been rung about private Persian Gulf funding for the Islamic State, the money from foreign donors is modest in comparison to self-funding, according to several U.S. officials who spoke on condition of anonymity.

SUBHEAD

After Germany’s Economic Development Minister Gerd Mueller last week accused Qatar of funding the Islamic State, U.S. officials said they have no evidence of any government funding the group.

Qatar was credited with helping negotiate Monday’s release of American journalist Theo Curtis, held for two years by the al-Nusrah Front, a rival Islamic militant group in Syria. Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey have aided the armed elements of the opposition to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, but deny funneling money to the Islamic State.

Private donations from states that have weak intelligence or enforcement mechanisms are another matter. The Obama administration says it’s closely tracking private funds collected in Persian Gulf states through mosques or via social media, destined for extremist groups in Syria and Iraq.

Several terrorist leaders and fund raisers have been sanctioned since May, and State Department and Treasury officials say they’re working with their counterparts in the Gulf region to ensure that any private donations are intercepted.

Charitable fundraising networks have raised hundreds of millions of dollars intended to benefit the Syrian people since the armed uprising against Assad began three years ago. Some fund raisers, especially in places such as Kuwait that don’t monitor money flows as carefully, have used the humanitarian crisis as a cover for soliciting donations for extremists, according to State Department and Treasury officials who were not authorized to be quoted.

That makes finding choke points to cut off the funding a challenge.

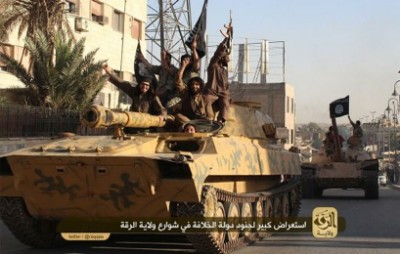

While the U.S. military launches airstrikes in Iraq against militants and their weaponry — much of it American hardware abandoned by Iraqi forces — other agencies are seeking ways to deplete the Islamic State’s coffers.

Those efforts include targeting distribution networks for middlemen selling oil from the Islamic State, strengthening anti-money laundering laws, improving financial intelligence and working with other governments to find chinks in the group’s financial armor.

“This new model is very different, but there are some pressure points we could apply,” said Fishman, former director of the Combating Terrorism Center at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. Aside from targeting illicit oil brokers, authorities can go after the bulk of the group’s reserves.

“It’s not totally clear where they’re storing all this money, but there may be ways to actually go after it,” he said. Whether or not it’s in a bank account, “you’ve got to put it somewhere.”

Florida Times Union

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.