In the brutal calculation of Middle East politics, the baseline for friendship has always been simple: The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

In the brutal calculation of Middle East politics, the baseline for friendship has always been simple: The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

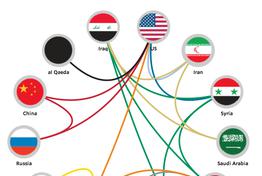

By that standard, the Islamic State extremist group is creating friendships aplenty. An odd set of bedfellows or potential bedfellows, transcending geographical, ideological and alliance bounds, is emerging from the ranks of those threatened by what many see as the most dangerous militant movement in a generation.

Shiite Muslim Iran and Sunni Muslim Saudi Arabia, for instance, have been bitter foes since at least 1979, when the Iranian revolutionary government of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini hoped to inspire similar revolutions in the Sunni world. But both countries now fear Islamic State’s armed radical Islamist movement, which seeks to usurp their own claimed leadership of the Muslim world.

That led Iran and Saudi Arabia to independently back the same candidate to lead Iraq, in a push for a new government that might unite Sunnis and Shiites to battle Islamic State. This week, Iranian and Saudi diplomats held a rare meeting to consult.

Turkey has long distrusted and worked against ethnic Kurds, especially a violent splinter group known as the PKK that operates out of the mountainous environs of northern Iraq. But the Turks looked the other way when Syrian Kurdish militias affiliated with the PKK played a starring role in the rescue from Islamic State fighters of thousands of Yazidis stranded on a mountainside.

Russia and the U.S. are at loggerheads in Ukraine and elsewhere, including the Middle East. But they agree that the sort of violent Islam practiced by Islamic State, which now controls large swaths of Iraq and Syria, endangers the global order in which both countries compete for influence.

Islamic State even has had a falling out with al Qaeda, the group that spawned it. Al Qaeda’s official Syrian branch, known as the Nusra Front, is outflanked and mocked by Islamic State. So Nusra has joined the fight against Islamic State, clashing violently on the battlefields of Syria.

These countries and movements may be at odds over nearly everything else, but nothing focuses the mind like a mortal threat, say some analysts and former top security officials. Given not only Islamic State’s savagery but its potential to overthrow regimes and spill over borders, they all seem to agree on only one thing: It needs to be stopped.

Lacking a coalition of the willing, the Obama administration should muster up a sort of alliance of the unwilling, these analysts argue. Whether that is possible, and whether the U.S. has the guile and clout to unite such disparate forces—either formally, or more likely in a combination of overt, covert and arm’s-length arrangements—is an open question.

“It has to be patched together, somewhat ad hoc, with maybe some sort of informal and even clandestine agreements on who does what,” says Zbigniew Brzezinski, a former U.S. national-security adviser.

In a region where states such as Iraq and Syria are literally fragmenting, Mr. Brzezinski urges an approach focused on the handful of what he categorizes as truly “viable” states—Turkey, Iran, Egypt, Israel and Saudi Arabia—to confront Islamic State, which also is known by the acronyms ISIS and ISIL.

U.S. officials, who privately concede they have no great options for bringing Islamic State to heel, recognize the allure of such a new alignment. President Barack Obamahas referred obliquely to the possibility in several public comments in the past week or so, and officials say privately they are exploring ways to form a working coalition.

Fear over the spread of Islamic State means parties often at odds now share a common enemy.

But U.S. officials agree that matchmaking such often bitterly antagonistic bedfellows is no simple task. When asked about the possibility that U.S. warplanes might be attacking Islamic State alongside the army of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad—whose overthrow is an explicit goal of American policy—State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki this week cautioned: “Just because the Syrian regime may be taking on ISIL or speaking publicly about that, and certainly the United States is, that certainly doesn’t mean we’re on the same side of the coin here.”

The challenges go well beyond simply getting mortal enemies to work together. Even when such arrangements can be forged, they are by nature fraught, filled with internal contradictions and practical pitfalls.

Because the deals are often secret, all sides tend to freeload, collecting the benefits from the other side while not really cooperating themselves. For example, the Obama administration worries that the Assad regime could take advantage of U.S. airstrikes against Islamic State fighters to keep its own ground troops focused on fighting U.S.-backed Syrian rebel groups.

And the closer the U.S. moves toward an enemy, the more likely it is that longtime friends get upset. For example, edging too close to Iran could spike efforts to keep Israel and Saudi Arabia on board, and vice versa.

“If you cooperate with one group, you lose another,” says Emile Hokayem, a Middle East security analyst with the International Institute for Strategic Studies. “It looks good on paper, but it’s impossible to implement.”

Still, recent events in the region have shown how nations normally or publicly at odds can work together behind the scenes when their separate interests converge. Relations between Egypt and Israel have grown increasingly strained. But the two have worked in lock-step recently to squeeze the Palestinian Hamas organization, which both see as a threat.

And even as the U.S. and Iran have vied for power and influence in Iraq they have learned to coordinate when they perceive common interests.

Beyond videos of executions, the extremist group known as the Islamic State, or ISIS, also apparently posts footage of members burning marijuana plants and smashing liquor bottles — drugs and drinking are banned under its version of Islamic law.

“We are watching you, and you are watching us. If you look for cooperation in the field, you can find it. And when you find it, it will be with the permission of the leaderships,” says Hossein Sheikholeslam, a former Iranian parliamentarian and now a foreign-policy adviser to Iran’s hard-line speaker in parliament.

Indeed, the most intriguing reality emerging in the struggle against Islamic State is how the U.S. finds itself pulling in the same direction as Iran, the main regional supporter of Mr. Assad’s Syrian regime. Islamic State’s hyper-sectarian Sunni fighters already have taken over a big chunk of Syria, and have gone on the offensive against Shiite militias and the Shiite-led Iraqi government Iran supports.

Both the U.S. and Iran deny overt or covert coordination. Yet Iran joined the U.S. in pressuring Iraq’s polarizing leader Nouri al-Maliki to step down. And both the U.S. and Iran are lending direct military aid to Kurdish fighters in Iraq to counter Islamic State.

Both sides are quick to point out their many disagreements, and are careful to fence off other issues from negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program. At the same time, some observers on both sides believe that a nuclear deal could improve U.S.-Iranian cooperation in other areas, such as fighting Islamic State.

“I am cautiously optimistic about what we might be able to do with Iran,” says Brent Scowcroft, another former national-security adviser. “If in fact we can make any kind of breakthrough on the nuclear issue, I think that opens the possibility that we may be able to treat Iran very differently, and their attitude may be very different.”

Mr. Scowcroft, who advised Presidents Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush, cautions that he “wouldn’t try to oversell” the possibilities with Iran. In an indication of the obstacles, the Obama administration on Friday announced some additional economic sanctions against Iran because of its nuclear program.

Others are more skeptical of a working U.S. relationship with Iran or, especially, Syria. That is partly because of a problem in trying to exercise influence through intermediaries: It is never clear how much influence the intermediaries actually have.

While Iran has been a major backer of Mr. Assad, that doesn’t mean his regime follows every Iranian order, according to Iranian and many U.S. analysts. The Assad regime has resisted or undermined several Iranian initiatives to broker deals to tamp down violence in Syria, say people familiar with these situations.

“I can tell you who are not bedfellows: Iran and the Assad regime,” says Ryan Crocker, former U.S. ambassador to both Iraq and Syria. Mr. Crocker, however, suggests an even more provocative possibility: a de facto alliance with the Nusra Front—the al Qaeda offshoot in Syria (and U.S.-designated terrorist outfit) that is one of the few groups directly battling Islamic State.

Nusra already works openly with U.S.-backed rebel groups in Syria, and it maintains communication with U.S.-ally Qatar, which this week helped engineer the release of an American journalist being held by Nusra. Many took this as a signal that Nusra wants to work through the Qataris to be seen as player in any anti-Islamic State configuration.

If the U.S. chooses to launch airstrikes Mr. Obama is considering against Islamic State inside Syria, and Nusra fighters then make inroads battling them, the U.S. would confront “a very interesting decision” on whether to openly include Nusra as part of a larger group willing to help take on Islamic State, Mr. Crocker says.

Another U.S. ally critical to winning the battle is Turkey, a Muslim country whose long border with Syria includes areas Islamic State controls. The U.S. and other countries have been concerned about Turkey’s support for some hard-line Islamist groups, though not Islamic State, and hope it now will work harder to prevent Islamic State’s growing body of foreign recruits from moving across the Turkish border to reach Syria.

Turkey already is averting its eyes to the arming of Iraqi Kurdish groups by both the U.S. and Iran as Kurdish militias battle Islamic State. The Iraqi Kurdish groups have forged close ties with the Turks in recent years, after decades of enmity. Some analysts say Turkey, as well as the U.S., also may eventually have to accept a more active role for Syrian Kurdish militias who are facing down Islamic State directly, despite those militias’ links with Kurdish militants who have attacked Turkey in the past.

Mr. Crocker suggests that, in a cooperative international effort, a wealthy country such as Saudi Arabia might be persuaded to give preferential loans to financially strapped Turkey in return for helping more in the struggle against Islamic State.

The Saudis, for their part, have already had to swallow hard and accept for the first time a Shiite-led government in Iraq. They will now have to swallow harder, many analysts say, and encourage Sunni tribes within Iraq to follow that government’s lead against Islamic State if it is to be defeated.

But the Saudis also are deeply suspicious of other players in a potential coalition, not least the U.S. They mistrust the Obama administration because it didn’t robustly support less-extreme Syrian opposition groups when Islamic State was just emerging. They are angry at Turkey and Qatar for supporting Islamic groups the Saudis consider too radical. And they consider Iran a threat to their interests at least as large as Islamic State.

Still, in a sign that a common enemy may be pulling even the Iranians and Saudis a bit closer, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister this week met with an Iranian deputy foreign minister, the highest-level encounter since the election of Iranian President Hasan Rouhani last year.

The Islamic State threat also is providing at least some common ground among the U.S. and its colleagues in the big-powers club, Russia and China.

The U.S. sees Islamic State as not only a threat to its interests in the Middle East but also a potential source of terrorist attacks. Russia sees a force that threatens to build ties and stir up more activism among the Chechen Islamists with whom PresidentVladimir Putin has waged a bloody struggle. China sees a group that threatens to inspire more activity among already-restive Islamists in its northwestern Xinjiang province.

Still, Washington’s tensions with both China and Russia on other fronts are getting in the way of cooperation these days, especially since Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its intervention in eastern Ukraine.

Whatever the level of international cooperation against Islamic State, one question is what form it might take. There is little communication between some of the odd-bedfellows candidates, and few existing alliances that would kick in elsewhere in the world under such conditions.

This means that cooperation likely would be ad hoc or secret, or that some new structure would be improvised. Zalmay Khalilzad, who served as ambassador to both Iraq and the United Nations, has suggested establishing a “contact group” in which regional players could coordinate strategy, and a presidential envoy to oversee execution of joint efforts on the ground.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.