Recep Tayyip Erdogan was no ordinary prime minister and he will certainly not be an ordinary president when he takes on the role on Thursday.

Since the 1950s, the Turkish president has been mainly restricted to performing ceremonial duties.

But for Mr Erdogan, this is a step up, not down.

Campaigning ahead of Turkey’s first direct presidential election on 10 August, he made clear he would play an active part and not follow the example of his predecessors.

“Erdogan was elected directly by the people in a highly politicised campaign, rather than being voted by the Parliament. It is unimaginable that this major change won’t make any difference to his authority as a president,” says pro-government journalist Yunus Goksu.

But the road to an executive presidency is full of challenges. His most important task will be to amend the constitution and change the nature of the post.

Previous ambitious presidents, among them charismatic politician Turgut Ozal (1989-93), all failed to break the boundaries of the role.

Their power was curtailed by the informal influence of the Turkish military-bureaucratic establishment, which has staged four coups since the 1960s.

In contrast, Mr Erdogan has successfully eliminated the influence of the military.

The country’s most effective security apparatus, the intelligence service MIT – which is headed by a former adviser – is also firmly under his control.

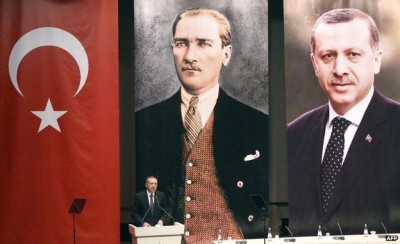

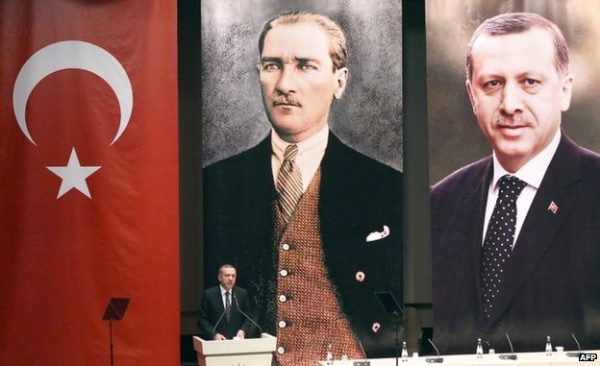

Mr Erdogan is seen as the most influential Turkish leader since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the Turkish republic.

And by becoming president, he will fill the post occupied by Ataturk himself from 1923-38.

Reviving the past

Under Ataturk, the presidential palace in Ankara was at the centre of Turkish politics.

He had almost absolute control over the military along with all the institutions in the country. His successor Ismet Inonu was also very influential.

In a way, the presidency is returning to what it was at its inception.

Mr Erdogan will initially revive dormant powers of the post, such as calling and presiding over cabinet meetings. He already has a strong influence over ministers.

He will also try to push the boundaries of his powers by overseeing the decisions made by the prime minister.

He will be influential in choosing ministers or preparing lists of candidates for the 2015 parliamentary election.

As prime minister, he intervened in ministerial or local decisions that would normally have fallen beyond his remit.

There is no reason to believe that he will not use his influence in a similar way as president.

His strong grip on the ruling AK party means that his candidate to succeed him as prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, will help him direct the government.

And as the only Turkish politician who can attract the support of Turkish nationalists as well as the Kurds, he will maintain a pivotal role in negotiations with the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) as well.

But to change the constitution to give himself more executive powers he will need to have a two-thirds majority at the parliament.

His AK party does not have that majority at the moment. The 52% of votes he polled as a presidential candidate was higher than his party ever gained in its previous eight victories.

And with less than a year before the polls, getting a majority will depend on Mr Davutoglu’s success.

Mr Erdogan secured his presidential poll victory by turning the polarisation in Turkish society surrounding his rule to his advantage.

Turks are divided between those who are devoted to him and those who have contempt for him. And he succeeded in maintaining his support despite a series of crises

Mr Erdogan has discovered that this polarisation works to his benefit, especially when fomented by a fragmented and feeble opposition.

Those who are devoted to him stay united and organised. However, there is hardly anything that unites his opponents other than their opposition to him.

Such a strategy may help win elections but it makes his rule look increasingly vulnerable. He struck a conciliatory tone after his presidential poll success that was different from his victory speech after local elections in March.

One main group he will have to win over is the 13 million-strong Alevi minority.

A significant part of the main opposition party CHP, the Alevis were also the main force behind the 2013 Gezi park protests.

Given their long-standing mistrust of the former prime minister, securing their support presents him with a major challenge.

But he will need to do so if he is to have room to manoeuvre in the increasingly volatile and sectarian Middle East.

BBC

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.