The Syrian refugee woman pushed through the crowd into the dusty grocery, where she was told she could register to receive donated blankets from an international aid agency. She didn’t stay long. The shopkeeper demanded a $13 bribe to put her name on the list.

The Syrian refugee woman pushed through the crowd into the dusty grocery, where she was told she could register to receive donated blankets from an international aid agency. She didn’t stay long. The shopkeeper demanded a $13 bribe to put her name on the list.

It would take her five days to earn that, laboring in the nearby bean fields.

“They won’t give me anything if I don’t pay,” said Zein, a 36-year-old widow with six children, leaving the shop empty-handed.

As a host of aid agencies struggle to provide help to the flood of Syrian refugees into Lebanon — so far numbering more than a million and counting — middlemen have worked their way into the cracks of the distribution system, demanding bribes and adding another layer of suffering for those fleeing the war.

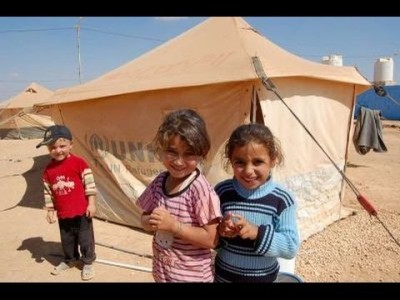

The most affected appear to be the poorest of the refugees — the around 160,000 who are unable to afford housing in Lebanon and end up in unofficial, ramshackle tent camps. In a series of interviews with The Associated Press, refugees in one such camp near the eastern town of Kab Elias said they often must pay anywhere from $3 to $100 in bribes to shopkeepers, local strongmen or municipal officials for a variety of tasks, particularly to get some consignments of aid or speed their registration.

“They are hungry dogs at the door,” said Sabha, a friend of Zein who also went with her to the grocery to seek blankets. “I don’t have money to pay for bribes. Where am I going to get it from?” The two women, like others in the camp, spoke on condition they be identified only by their first names, fearing for their security.

The U.N. refugee agency, UNHCR, oversees the bulk of aid distribution in Lebanon, working with 60 partner organizations. Most refugees who register with the UNHCR receive an ATM-like card which they can directly purchase $30 worth of food each month — eliminating any bribe-seeking middleman.

But the $30 runs out quickly, forcing those in the camps to turn to other charities. The smaller groups, in particular, often lack manpower to distribute aid themselves and so turn to local middlemen to register refugees to receive their shipments of food, medicine, blankets and other supplies — opening the door for abuses.

“It’s a common issue across all operations and we are well aware of it,” said Ninette Kelley, UNHCR’s representative in Lebanon. “There will always be people who try exploit refugees … It’s really so sad, because refugees are the most vulnerable in a community.”

She said it was unlikely to be widespread because of extensive checks. The UNHCR also conducts outreach to refugees, informing them its services are free and that they can report incidents of corruption.

But oversight is difficult amid the chaos of one of the world’s worst refugee crisis. Syria’s civil war has driven more than 2.6 million people into neighboring nations.

The governments of Turkey and Jordan have set up large, organized camps to take in many of the refugees. Lebanon, in contrast, has not allowed official camps, leaving almost no supervision over the dozens of small, informal encampments that have cropped up, particularly in the agricultural fields of the eastern Bekaa Valley.

Each camp is typically controlled by a strongman, known colloquially as the “shawish” — usually a refugee who has built up connections with local Lebanese officials or has prominent family connections among the refugees. The shawish often oversees the building of tents, sometimes demanding rent, and provides services for the refugees like securing lines of credit with local shopkeepers, finding them work or dealing with Lebanese officials — all for a fee.

For example, Zein and Sabha, a 32-year-old mother of five, each earn $4 a day each picking beans, but they have to give $1.65 a day to their camp’s shawish, who got them the job.

One recent day after work — their hands still stained with dirt — the two went to the grocery near their camp after hearing they could register there for blankets from the charity Caritas.

Inside the store, the shopkeeper stood before a large ledger.

“Is there aid coming?” asked Zein. “How much is it?”

Five thousand lira up front, then another 15,000 lira after receiving the aid, he said — altogether, about $13.30. The two women walked out.

Asked about the incident, Caritas spokeswoman Joelle El Dib said the organization’s policy is not to use middlemen and that the group was not aware of demands of bribes for its aid. She said the group would investigate the incident.

Seven aid workers with various organizations said relief groups are sometimes forced to use local shopkeepers or the shawish to register refugees. “The shawish is usually known as being corrupt. They can block access, and (charities) aren’t allowed to see the people, unless it’s with his permission,” said one aid worker.

“It’s almost impossible to check on whether aid is being properly delivered for a village. Now imagine for a million people,” another aid worker said.

The aid workers spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the problems.

The shawish in Sabha and Zein’s camp acknowledged that he takes money and argued that it was justified because he helps fellow refugees. His tent showed the benefits. It had electricity for a fan, while others go without power. There was a stack of extra blankets and a double bed — a contrast to the thin mattresses on the ground that most camp residents sleep on.

The camp is a collection of about a dozen tents thrown together from pieces of burlap and plastic and wood planks amid the bean fields, home to about 20 families. Sabha and Zein sat with other women in one tent, smoking cheap cigarettes as they spoke about the bribes.

“They control us,” Zein said of the shawishes and other middlemen.

One woman, Umm Ahmed, told how a driver for one charity demanded $7 to take refugees’ names to receive boxes of food and soap distributed by a nearby mosque.

Umm Nader, a mother of seven, said the shawish told her to pay a $30 bribe to speed up registration with the UNHCR, a service that is supposed to be free.

“The land, we pay for. The tent, we pay for. We pay for everything,” said another woman, Umm Hamid, mother of 10. “We’ve been hungry for a week.”

AP

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.