Waving the Russian flag and chanting “Russia! Russia!”, protesters in Crimea have become the last major bastion of resistance to Ukraine’s new rulers.

Waving the Russian flag and chanting “Russia! Russia!”, protesters in Crimea have become the last major bastion of resistance to Ukraine’s new rulers.

In the region’s capital, dozens of armed men seized the parliament building and raised the same flag.

President Viktor Yanukovich’s overthrow on Saturday has been accepted across the vast country, even in his power base in the Russian-speaking regions of eastern Ukraine.

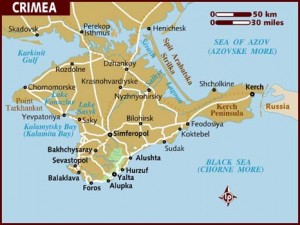

But Crimea, a Black Sea peninsula attached to the rest of Ukraine by just a narrow strip of land, is alone so far in challenging the new order.

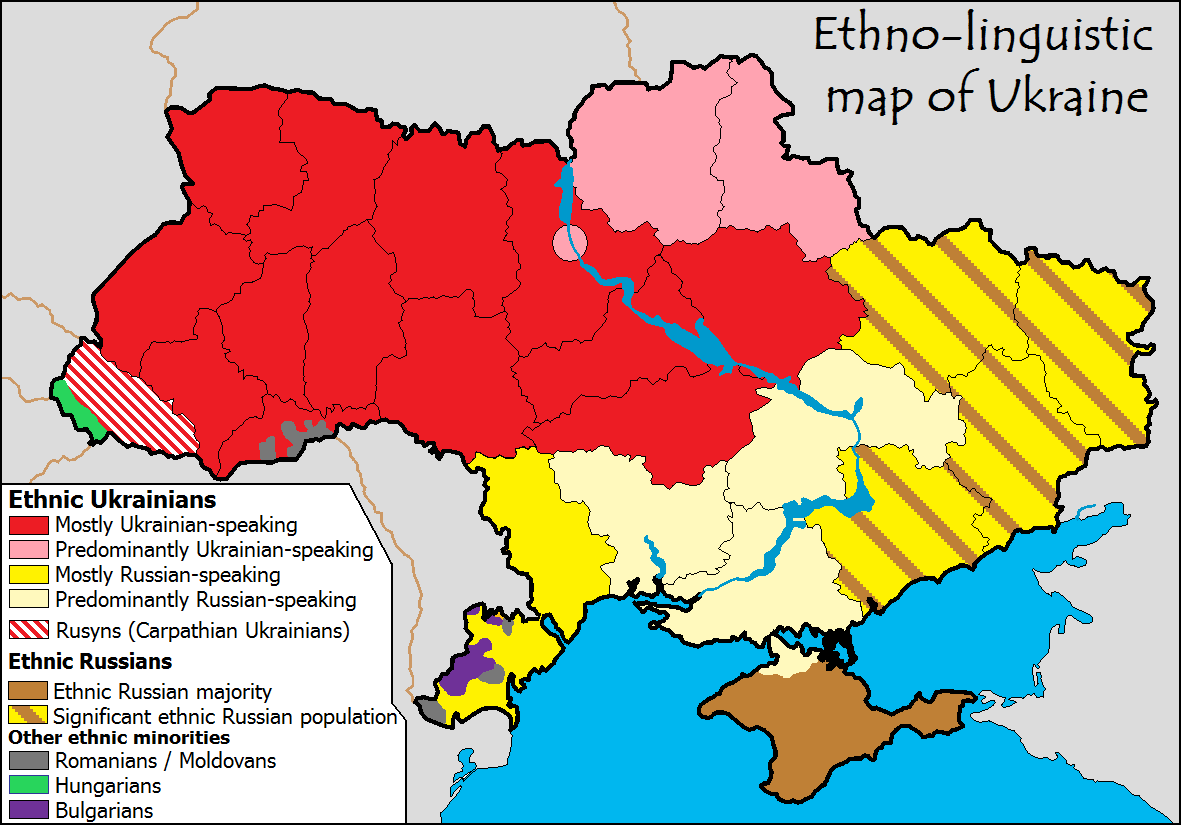

As the only Ukrainian region with an ethnic Russian majority, and a home to Russia’s Black Sea fleet, the strategically important territory is also now the focus of a battle between Russia and the West over the future of Ukraine.

Tensions are mounting in the Crimean capital Simferopol as separatists try to exploit the chaos after the changes in Kiev to press demands for Russia to reclaim the territory which Communist leader Nikita Khrushchev gifted in 1954 to the Soviet Ukraine.

Amid some shooting, 50 gunmen entered the parliament under cover of darkness. The regional prime minister spoke to them by telephone, but they had not made any demands or said why they were there. They had promised to call back but had not done so.

About 100 police gathered in front of the building, and a similar number of people carrying Russian flags marched up chanting “Russia, Russia” and calling for a Crimean referendum.

One of them, Alexei, 30, said: “We have our own constitution, Crimea is autonomous. The government in Kiev are fascists, and what they’re doing is illegal.”

Washington has warned Moscow not to send in tanks, an action that could result in yet another war in a region that has been fought over – and changed hands – many times in history.

But President Vladimir Putin flexed his muscles on Wednesday, putting military forces in western Russia on alert and saying Russia was acting to ensure the security of its facilities in the Crimean port of Sevastopol. On Thursday he put war planes on alert too.

The view from separatists in Crimea is that there has never been a better time to appeal to Moscow for help than now.

“I crossed two oceans and four seas with the Russian navy, and now I have fascists telling me what to do?” said Daniyel Romanenko, a 73-year-old retired officer, portraying the new Ukrainian leadership in the worst possible terms in a country that was overrun by Nazi Germany in World War Two.

“We should be given the choice to unite at last with Russia,” he said at a rally in Sevastopol, wearing his uniform.

MOB RULE

Crimea’s balmy climate once made it a favoured holiday destination for Russian tsars and Soviet leaders. Vineyards, orchards and the “green riviera” along its southern coast make for some stunning scenery.

But even before the national parliament in Kiev stripped Yanukovich of his powers on Saturday, after three months of protests by largely pro-Europe demonstrators, there were rallies in Crimea by worried ethnic Russians.

Although he was little loved in Moscow, Russia had backed Yanukovich and his departure reduces the Kremlin’s ability to influence Ukraine.

For the more than 1 million ethnic Russians in Crimea, it increases uncertainty, and many want protection by Mother Russia, with whom cultural and religious ties are strong.

“We don’t have a legitimate government so we have to look out for ourselves,” said Vladimir, a 37-year-old businessman.

Taking matters into their own hands, separatist-minded protesters at a rally on Sunday voted to appoint Alexei Chaly, a Russian businessman, as the de facto mayor of Sevastopol in a show of hands.

The next day the presence of a large crowd on the streets outside a meeting of the city administration ensured his appointment could not be blocked.

The chaotic events, followed by more protests on this week, and more calls for secession, underline how difficult the transition of power may be in Ukraine, especially in Crimea.

“BANANA REPUBLIC”

Rumours that protesters from Kiev’s barricades might be on their way from the capital to put down separatist moves have prompted some Crimeans to create informal self-defence units.

Rumours that protesters from Kiev’s barricades might be on their way from the capital to put down separatist moves have prompted some Crimeans to create informal self-defence units.

Around 3,000 men have signed up in Sevastopol alone, with military veterans and former members of the Berkut riot police training the younger recruits, the organisers say.

In other parts of Ukraine, particularly Kiev, the Berkut is despised as the force which fired on protesters.

“We need to protect ourselves from the armed criminals coming to Crimea in masks to cause unrest. They’ve turned Ukraine into a banana republic,” said Gennady Basov, the leader of the Russian Bloc party that represents ethnic Russians.

Unification with Russia is not the party’s main aim, but it believes that splitting Ukraine down the middle – between Russian-speaking areas in the east and regions where Ukrainian is predominant in the west – makes economic and cultural sense.

“Most of the economic strength of Ukraine is in the east – that’s where people actually work. In the west they just go to Kiev to protest,” Basov said, underlining ethnic Russians’ contempt for the protesters in Kiev, many of whom are from the west of the country.

Such remarks show how the protests in Kiev, triggered by Yanukovich’s decision in November to spurn trade and political deals with the European Union and rebuild ties with former Soviet overlord Moscow, have widened divisions in Ukraine.

For some ethnic Russians in Crimea, it was the last straw. Already connected to southern Ukraine by land that is only five km (three miles) wide at some points, the region seems to them to have less in common with the rest of the country than ever.

“The people don’t understand this was a revolution against a criminal government, they think it’s all Western influence. To them the people on the barricades are now greater enemies than the corrupt government they overthrew,” said Leonid Pylunskyy, a regional deputy for the conservative Kurultai Rukh party.

Pylunskyy is the fourth generation of his family to call Crimea home, but both his children participated in the Kiev protests – his son on the barricades, his daughter providing demonstrators with hot tea and sandwiches.

RUMOURS, RUMOURS

Barely an hour goes by without a new rumour of troops massing or protesters on their way from Kiev to “restore order”.

Putin himself stirred the pot by suddenly announcing a drill that involved putting forces in the west and centre of Russia on the alert. He may be sabre-rattling but is unpredictable and brooding after apparently losing a geopolitical tussle with the West over Ukraine which brought back memories of the Cold War.

Opinion polls suggest a majority of Russians still view Crimea, annexed by Russia in 1783, as a Russian territory.

But not all the peninsula’s residents are pro-Russia or against the new political situation, as was witnessed by confrontations between rival protesters outside the regional parliament in Simferopol on Wednesday.

The region is a patchwork of ethnic groups and the Tatars, now back in numbers after their ancestors were deported to Central Asia or Russia’s Urals region by Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, dread the idea of integration with Russian.

“In 1783 we fell under the power of the Russian empire and that’s when all our sorrows began. The (Crimean ethnic) Russians can look to Putin. We’re sticking with Ukraine,” Crimean Tatar leader Refat Chubarov said in an interview.

Chubarov outlined what he saw as deliberate moves by the ethnic Russians to fuel tension. “This is their plan: they’ve stoked the fires in Sevastopol, now they want to light the fires in Simferopol, so all Crimea burns,” he said.

“I hope I’m wrong but Russia could well decide to deploy its forces in Crimea,” Chubarov said.

BATTLE LINES DRAWN

Ethnic Tatars and ethnic Russians faced off outside the parliament on Wednesday but dispersed after scuffles.

Conflict is hardly unusual for the people of Crimea.

It was inhabited or invaded by Scythians, Greeks, Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Kazhars, Kipchaks, Turks and Mongols, and was part of the Roman and Byzantine empires before it became part of the Russian empire.

There were fierce battles on Crimea during World War Two, when it was occupied by the Nazis, and during the Crimean War which Russia lost to an alliance of France, Britain, the Ottoman empire and Sardinia.

“We’re used to being fought over. We’ve had the Turks, British, Germans and now this,” said Igor, a 26-year-old businessman from Simferopol.

Reuters

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.