The last known man to see Robert Levinson alive in Iran now says that the CIA contractor who disappeared in 2007 was definitely detained by Iranian authorities and is almost certainly still in Iranian custody if he remains alive.

The last known man to see Robert Levinson alive in Iran now says that the CIA contractor who disappeared in 2007 was definitely detained by Iranian authorities and is almost certainly still in Iranian custody if he remains alive.

Dawud Salahuddin, an African-American convert to Islam who met with Mr. Levinson on Iran’s resort island of Kish in 2007, told the Monitor in Tehran that they were detained at the Maryam Hotel on March 9, 2007, by six plainclothes policemen and then separated.

“They took me away, and when I left – we were down in the lobby – Levinson was surrounded by four Iranian police,” says Salahuddin, who spent the night in jail.

When he returned the next day, Salahuddin spoke to the Indian manager of the hotel, who told him Levinson was gone: “He told me that, and without saying a word let me know that the guy did not leave on his own accord, that he was in custody. But he didn’t have to say it out loud for me to know that. And he wouldn’t have said it…. I understood that something was wrong.”

Rogue operation

Salahuddin, a fugitive who has lived in Iran since carrying out a 1980 murder in Maryland on behalf of Iran’s revolutionary regime, says the flurry of publicity and revelations about Levinson’s CIA connections could be a sign of an impending release, though Levinson’s family has more than once been given false hope by the US government.

The retired FBI agent disappeared from view. For years, the US government insisted that Levinson was only a private citizen working for a private client. Last week, the Associated Press revealed that Levinson was in fact part of a rogue CIA operation seeking to collect intelligence on Iran’s financial dealings and nuclear program. He had told his CIA handlers that he was trying to cultivate Salahuddin as a source who had deep contacts in Iran.

It appears that Iran has also been playing with the truth. Yesterday, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif restated Iran’s official position, telling CBS News that Iran has “no trace” of Levinson, and if he were still in Iran, he was not under government custody.

Hope?

Salahuddin told the Monitor in an exclusive face-to-face interview in Tehran and by telephone that he believes an arrangement may have been reached with Iran to secure Levinson’s release. When the US was insisting Levinson wasn’t a spy, it was hard for Iran to admit it had detained him. But with the evidence of US deceit on the CIA link, “it allows the Iranians to justify all their lies for all these years because they had an actual intelligence operative, which is quite valid,” he says.

“So if he shows up in a three-piece suit, clean shaven, and brand new shoes in Muscat [Oman] in the next couple of days, I won’t be the least bit surprised,” says Salahuddin. Oman is one venue where secret talks were held between the US and Iran ahead of the deal to temporarily suspend the progress of the country’s nuclear program.

Salahuddin revealed fresh details of his fateful meeting with Levinson in his Monitor interview. The soft-spoken Salahuddin – who was born David Theodore Belfield – wore his trademark black woolen beret that was his signal to Levinson the day they met.

Speaking with an American accent that has not faded after more than three decades in Iran, where he has been forced to live since impersonating a postman and assassinating a critic of Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution in Bethesda, Md., Salahuddin says he has paid a “high price” for challenging the official Iran line that it has no knowledge of Levinson’s whereabouts.

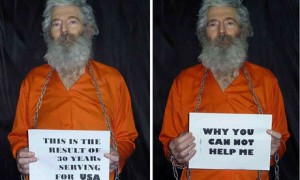

Since proof-of-life video and photographs of Levinson last emerged in 2010 and 2011 – showing a man with a thick white beard, dressed in an orange Guantanamo-style suit and holding pleading messages – there has been no sign of life of the father of seven.

As Salahuddin tells the story, Iranian intelligence caught Levinson – whose specialty was following the financial trails of crime and mafia figures from Latin America to Russia – by “dumb luck.” Levinson, he says, made the “huge mistake” of booking them into the same room in Kish, which set off alarm bells for Iranian authorities.

“This was 2007, and I hadn’t been involved in anything [clandestine] like that since about 1995, so my instincts were very rusty. Because had I been thinking, I just would have gone to another hotel, because I know that every night the Iranians come by and check the passports.”

Salahuddin had an expired Iranian passport, “but they knew full well that I was not an Iranian,” he says. And Levinson’s American passport booked to the same room resulted in the arrests of the two men.

According to Salahuddin, Levinson had presented himself as an investigator looking into cigarette smuggling on behalf of British American Tobacco PLC.

According to Salahuddin, Levinson had presented himself as an investigator looking into cigarette smuggling on behalf of British American Tobacco PLC.

“He came to me under false pretenses … he was lying to me,” says Salahuddin. He says he told Levinson and Ira Silverman, the mutual acquaintance who put them together, that cigarette smuggling in Iran was a “state monopoly,” and so efforts to meet Iranian officials to curb it would not bear fruit.

Salahuddin says he also warned Levinson and Silverman that it might not be a good time for an American to come to Iran, just weeks after US forces in northern Iraq landed helicopters on an Iranian liaison office captured five mid-level Iranians in Erbil. “But they didn’t listen to me, and I assumed they knew something that I didn’t know. But they didn’t.”

So Levinson came to Kish, and Salahuddin flew there from Tehran.

“We had a nice, long six-hour conversation that afternoon and that evening,” says Salahuddin. They talked about Levinson’s career in the FBI, the money trails he had followed, and his role in bringing down John Gotti.

To Salahuddin, Levinson’s decades of experience as an investigator had yielded an obvious professionalism – at least in some aspects of tradecraft.

“He never says a word that he’s not fully in control of. He doesn’t speak loosely,” says Salahuddin. “And very personable, a very likable person. You wouldn’t at all mind sitting down and spending a day talking to him. Extremely bright, a very intelligent man, good knowledge of a lot of different things.”

Salahuddin was struck by Levinson’s devotion to his family. “His family was his life, a straight arrow, no messing around, nothing on the side, that kind of guy,” says Salahuddin.

After his own brief detention and Levinson’s disappearance, Salahuddin returned to Tehran, and called Levinson’s mobile phone and his Dubai hotel every four hours for two days.

“Then I understood that he never got back to Dubai,” says Salahuddin. “And the notion that somebody got this guy out of Iranian police custody, and kidnapped him or whatever, I realized that was simply not true. I understood when I left the lobby of the hotel, he’s going to be in Iranian police custody for some days, because that’s how they do things.”

Back in Tehran, Salahuddin inquired with someone he knew in Iranian intelligence, “because I was still buying into the story that [Levinson] was there to look into this cigarette smuggling thing,” he says. “I had no clue that I was supposed to be in the process of being massaged as a possible asset, or source. Hey, that was the last thing on my mind. I had never entertained any notions like that…. And frankly, I don’t feel so patriotic, OK? I’m not the guy to come to for that.”

In custody

Salahuddin’s acquaintance called an Iranian official, who he says was then-Interior Minister Mostafa Pour-Mohammadi, who today is minister of Justice. He overheard one side of the phone call.

“The question was not whether or not this guy had been disappeared. It was clear that they had him in custody, from the conversation,” recalls Salahuddin. “What I was telling him was, ‘You don’t really have anything here. You let the guy go, and you’ll save yourselves a lot of problems down the road.’ But I was going on the basis of this cigarette thing.”

“I got the impression that after a few days, he would be released. Of course, that didn’t happen, and then the Iranians began this seven-year-long story that they have no idea where he is,” says Salahuddin. “But hey, governments, all governments, are liars. So for anybody to say that the Iranians are so devious or whatever, all they need to do is look in the mirror, because they do exactly the same thing.”

News that Levinson was a CIA contractor “made a lot of sense to me, but to tell you the truth from the beginning until now, I never even thought about that,” says Salahuddin. “It did make me feel differently about him…. Nobody likes to be played for a fool, and that’s basically what they were doing with me.”

Salahuddin says he had nothing to do with Levinson’s disappearance: “It’s like this … I know what I did, and I know what I didn’t do. I know what my intentions were, and I don’t have any conscience problem whatsoever about any of that,” he says. “I was not involved in the guy being taken. In fact, I’m the only one who protested. I’m the only person here who’s on record saying that the guy has never left Iran.”

Since Salahuddin first publicly stated in 2007 that Levinson had been taken into Iranian custody, he says, he has not been provided a new passport or travel documents, which had until that point been “automatic” for him. He considers himself to be the “last American hostage in Iran.”

“I’ve seen all those things, that I set the guy up and all that,” says Salahuddin. “Listen, I don’t do things like that, that’s not a part of my makeup. I can hurt people, but I wouldn’t hurt anybody like that – that’s cheap stuff, man. That’s real cheap stuff, and I never, ever got involved with stuff like that.”

CSM

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.