The Dead Sea has been rapidly disappearing for 50 years, one of the world’s natural wonders careening toward ecological collapse in a region more often focused on political conflict.

The Dead Sea has been rapidly disappearing for 50 years, one of the world’s natural wonders careening toward ecological collapse in a region more often focused on political conflict.

On Monday, Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority agreed on an ambitious plan to begin refilling the ancient salt lake with briny water pumped from the Red Sea — and relieve local shortages of fresh water at the same time.

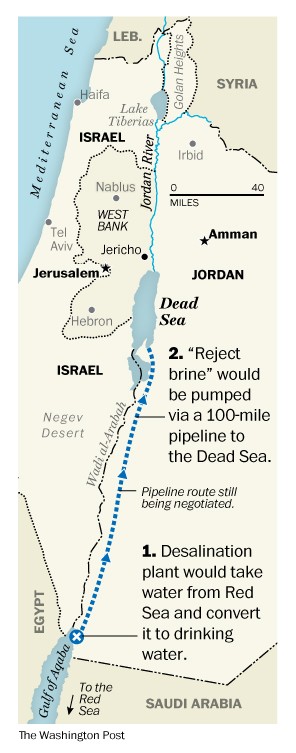

In the first stage of what could become a massive joint initiative, private investors will be asked to finance construction of a large desalination plant in Jordan, on the Gulf of Aqaba. The plant would suck billions of gallons from the Red Sea and convert it to drinking water that would be shared by Israel and Jordan. Israel, in turn, would increase the amount of water it sells to the Palestinian Authority by as much as 30 million cubic meters a year.

Billions of gallons of “reject brine” — essentially, super-salty water created by the desalination process — would be pumped via a new, 100-mile pipeline and discharged into the Dead Sea, in quantities hoped to be large enough to buy some time and slow the lake’s disappearance.

The initiative was announced two days before Secretary of State John F. Kerry makes his latest trip to Jerusalem to nudge forward peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. Although the Dead Sea project is not directly linked to those talks, Kerry has said that increasing the supply of water in the West Bank is a key part of economic development there, which the United States sees as a vital stepping stone to peace.

The initiative was announced two days before Secretary of State John F. Kerry makes his latest trip to Jerusalem to nudge forward peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. Although the Dead Sea project is not directly linked to those talks, Kerry has said that increasing the supply of water in the West Bank is a key part of economic development there, which the United States sees as a vital stepping stone to peace.

The project has been under study for years. Negotiators for the three sides had to navigate the cost of rehabilitating a natural heritage site they all border and address the region’s pressing water problems. Jordan and the Palestinian Authority are chronically short of fresh water, and although Israel has a surplus — it has invested heavily in desalination and enjoyed a recent spate of good rainfall — that could quickly change in a drought.

At a signing ceremony in Washington — witnessed by representatives of the U.S. State Department and the World Bank — Israeli, Jordanian and Palestinian officials said the agreement was proof that they could come to terms on a life-and-death issue.

“It is no joke when people are looking for a liter of water to drink,” said Hazem Nasser, Jordan’s water minister. “The role of water in our region is completely different from anywhere in the world.”

Much about the project remains to be worked out. Bids from private investors will be solicited next year, with estimated construction costs for the plant and pipeline running anywhere from $500 million to about $1 billion. The sensitive issue of fees for the water and the exact routing of the pipeline remain to be negotiated.

The first drop of brine would probably not be deposited into the Dead Sea before 2017.

But if it works out, the agreement could pave the way for even more “Dead to Red” investment. The World Bank has conceptualized a $10 billion program — once envisioned as a canal between the two bodies of water but now possibly involving a series of pipelines and desalination plants.

“This is a historic agreement that realizes a dream of many years,” said Silvan Shalom, Israel’s water and energy minister. “The agreement is of the highest diplomatic, economic, environmental and strategic importance.”

And, hopefully, not too late.

The Dead Sea is the lowest spot on Earth, a vast, sulfurous and strange body of water landlocked in a great rift valley, a cradle of civilizations and religions. It gets its name from the fact that no plants or animals can live in its mineral-saturated waters. The sea is mentioned a few times in the Bible and is located just south of Jericho, near the sites of the ancient cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. The Crusaders called it the Devil’s Sea.

Today, it is a popular destination for tourists, who pack themselves in mud from its shores and float in water that is about 10 times as salty as the ocean. There are salt ponds, potash mining and a mystical vibe — with lots of quicksand and sinkholes.

Thanks to humans, the sea has been dying for years — its spa resorts, once seaside, now so far from the shore that visitors have to hop a trolley or hoof it to reach their salty baths.

The water level has dropped more than 80 feet in the past half-century as Israeli and Jordanian agricultural projects reduced the flow of the Jordan River to a trickle. The decrease in inflow from the river and the desiccation of local natural springs have shrunk the surface area of the lake by one-third.

Government scientists and World Bank officials said the desalination deal would be only a small step on the long and uncertain path to stabilizing the Dead Sea. The 26 billion gallons of brine that would be added each year is a fraction of what is needed to maintain the sea’s current water level.

Some environmental groups, such as Friends of the Earth Middle East, say the transfer of brine into the sea could have “detrimental impacts.”

Scientists say they will monitor the sea for any negative effects. A mixing pool will be created at the southern end, where the brine will be added, and dammed off from the rest of the sea, so they can study the interaction of water from the two places.

Washington Post

Photo: From left: Sylvan Shalom, Israeli regional development minister; Hazem Nasser, Jordanian water and agriculture minister; and Shaddad Attili, head of the Palestinian Water Authority, shake hands after signing the deal.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.