Despite a week of daily negotiations between the United States and Russia over the planned destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons, the two sides were still deeply split on a fundamental point when Secretary of State John F. Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov met last Tuesday.

Despite a week of daily negotiations between the United States and Russia over the planned destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons, the two sides were still deeply split on a fundamental point when Secretary of State John F. Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov met last Tuesday.

The scheduled 45-minute session Tuesday on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly took place in a tiny Russian meeting room at the United Nations, with an enormous portrait of President Vladimir Putin on the wall. It ran for about 90 minutes, with Kerry and Lavrov, flanked by their U.N. ambassadors and other aides, making pencil edits to a four-page draft that represents a major departure in each country’s approach to the Syrian civil war.

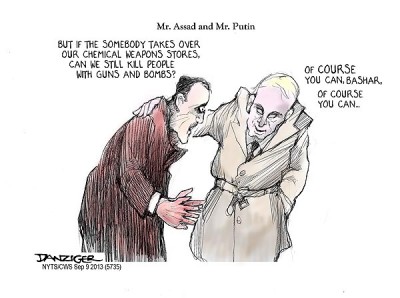

Russia wanted more lax ways to make sure that ally and arms client Syria complied with the agreement to give up its toxic stores; the United States wanted a toughly-worded U.N. Security Council resolution that spelled out what Syria had to do and the consequences Damascus would face for reneging.

The resolution approved unanimously by the 15-member Security Council three days later split the difference, but not before some drama that included a tense, 11 p.m. telephone call between Kerry and Lavrov.

“That was a tough conversation,” a senior State Department official said Saturday, with Kerry suggesting that their mutual goal of getting the agreement completed during the General Assembly was in peril. Several U.S. officials and other diplomats spoke on the condition of anonymity provided a look at the makings of the deal, because much of the discussion with Russian officials was confidential.

The Russian position leading up to the General Assembly meeting had stressed a lesser role for the Security Council, which the U.S. side saw as a way to water down a historic agreement to rid Syria of toxic weapons. Russia preferred to leave most responsibility for reporting on Syrian progress or the lack of it to the U.N.-affiliated Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, which has no real enforcement power.

“Their approach initially was, ‘Syria voluntarily does this,’ and our whole frame was, ‘Are you kidding? This regime just gassed more than 400 children,’ ” Samantha Power, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, said Saturday.

The United States and Russia, which back opposing sides in the conflict, had reached an agreement in principle earlier this month in Geneva to put Syria’s chemical weapons stores under international control. That agreement averted imminent U.S. cruise missile strikes on Syria in protest over the poison gas massacre of more than 1,000 people on Aug. 21. Syria agreed to give up its weapons under heavy pressure from Russia.

The United States and Russia, which back opposing sides in the conflict, had reached an agreement in principle earlier this month in Geneva to put Syria’s chemical weapons stores under international control. That agreement averted imminent U.S. cruise missile strikes on Syria in protest over the poison gas massacre of more than 1,000 people on Aug. 21. Syria agreed to give up its weapons under heavy pressure from Russia.

A Security Council vote endorsing the program would be the first firm action at the world body since the Syrian war began. All previous attempts to punish or condemn Syrian President Bashar al-Assad were blocked by Russia, which, like the United States, holds a veto.

“We really did believe there was no viable path forward at the Security Council, and it was not for lack of probing,” Power said Saturday. “We couldn’t even get a press statement out of the Security Council the day of the attack condemning the use of chemical weapons. It was that blocked.”

Despite the basic agreement to act at the Security Council, negotiations were difficult, several officials close to the talks said. The framework agreed to by Kerry and Lavrov in Geneva left many things vague — chief among them the ways Syria would be held to account.

The session at the United Nations on Tuesday was a breakthrough, officials said, but did not resolve the last sticking points over language. “Things like we want a ‘shall’ and they want a ‘should,’ ” one official said.

It is such details that can make the difference between a powerful resolution and a weak one.

Translating the framework worked out by the two top diplomats on Sept. 14 into binding requirements for Syria “was not easy given the frictions we have had with the Russians on Syria,” and the challenge of the task itself, a senior Obama administration official said.

The resulting deal sets an ambitious schedule for the seizure and destruction of one of the world’s largest remaining stores of the widely banned weapons, and does so while fighting continues.

After that session Tuesday, Power met again with Vitaly Churkin, Russia’s ambassador to the U.N., and a small team of negotiators. They had made some headway by Wednesday, but Kerry was concerned that the week was slipping by, the State Department official said.

Following a late dinner, Kerry called Lavrov on Wednesday night. Lavrov did not want to have a detailed discussion, officials said, but negotiators stayed up most of the night. By the next day, Power and Churkin had a draft text, and Kerry and Lavrov agreed to meet again.

They sat together with their aides for about 45 minutes and approved the final version, then met briefly alone, one official said. The meeting ended with a warm handshake. The U.S. and Russia then finalized a critical technical agreement on arrangements and timetables for inspections and presented it to the OPCW, which had to allow a 24-hour consideration before its vote.

The OPCW, meanwhile, scheduled a vote on the technical plan at 4 p.m. Friday, providing just enough time for the Security Council to vote on its landmark resolution at 8. But Iran raised late concerns about the OPCW text, forcing a delay in the vote .

Lavrov had extended his stay to vote on the measure personally, as had British Foreign Secretary William Hague and others. Hague’s U.N. envoy, Mark Lyall Grant, posted an anxious tweet, warning that the U.N. vote might be scuttled.

The OPCW, headquartered in The Hague, voted about 6:30, and Lyall Grant tweeted, “White smoke in the Hague.”

The Security Council vote just after 8 p.m. was unanimous.

The Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.