CARACAS, VENEZUELA — All week long, from the moments before President Hugo Chavez died and in the days that followed, the man Chavez picked to succeed him has thundered from the podium against oligarchs, transnational oil companies and the United States.

CARACAS, VENEZUELA — All week long, from the moments before President Hugo Chavez died and in the days that followed, the man Chavez picked to succeed him has thundered from the podium against oligarchs, transnational oil companies and the United States.

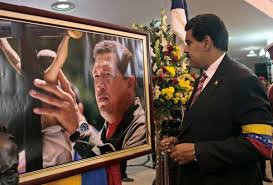

Nicolas Maduro, who was sworn in as president Friday after Chavez lost a battle with cancer, is poised to govern this oil-rich country until at least 2019 and carry on with the same policies as his boss.

On Saturday, the country’s electoral board said a presidential election, as mandated by the constitution after the death of a president, would take place April 14.

Minutes later, Venezuela’s coalition of opposition groups said it had decided to offer its candidacy to Henrique Capriles, a lawyer and governor of Miranda state who challenged Chavez in the presidential election in October.

Pollsters and political analysts say that Capriles’s charisma and seasoning as a campaigner could be too little to defeat Chavez’s chosen successor so soon after his death, which has left the country in an unprecedented state of loss. As Chavez’s loyal aide for a generation, the 50-year-old Maduro not only has the country’s sympathy vote but now controls the purse strings that have given the government a major boost in one election after another.

With the outcome of an election nearly foretold, many Venezuelans are asking themselves what kind of president Maduro might be — a conciliator open to healing wounds or a demagogue who uses his position to control all the levers of powers, as critics say Chavez did.

Once seen as reserved, Maduro has come out in recent speeches with not only the same bellicose rhetoric as Chavez but also a similar fire-and-brimstone cadence. He has pledged to keep alive El Comandante’s flame by saving the poor from greedy elites operating here and in the United States, which he calls Venezuela’s “historic enemy.”

“Sooner rather than later the imperialist elites who govern the United States will have to learn to live with absolute respect with the insurrectional peoples of America,” he said moments after receiving the presidential sash in Friday’s inauguration. “We’ve decided to be free, and nothing and no one will take that independence that was re-conquered with our commander Hugo Chavez at the helm.”

As Maduro became more visible in recent weeks, people here wondered if the beefy former bus driver would as president turn out to be the calm apparatchik some diplomats found him to be. That Maduro was said to be pragmatic, a negotiator with the patience to sit down with adversaries, a leader open to resolving the polarization Chavez helped create in 14 years in power.

But the picture that is emerging of Maduro — particularly in the past four days of mourning for Chavez, who died Tuesday afternoon — is of a leader who appears to be ready to accelerate the former president’s agenda. That is shaping up to mean insults and threats such as the ones Maduro has issued this past week. And for Venezuela’s beleaguered opposition and the press, it may mean renewed efforts to corral them.

“I thought he represents the most orthodox of socialist thought, of the doctrinaire socialist thought that Chavez defended,” said Demetrio Boersner, a historian and columnist. “He’s doing all he can to apparently speak like Chavez and follow Chavez’s style in all its details so that the popular masses see him as a kind of son of Chavez, that he’s saying what the fallen caudillo [strongman] would say.”

“I thought he represents the most orthodox of socialist thought, of the doctrinaire socialist thought that Chavez defended,” said Demetrio Boersner, a historian and columnist. “He’s doing all he can to apparently speak like Chavez and follow Chavez’s style in all its details so that the popular masses see him as a kind of son of Chavez, that he’s saying what the fallen caudillo [strongman] would say.”

Maduro, to be sure, was the man chosen by Chavez as his successor, a decision Chavez made public on Dec. 8, when he went on national television to instruct Venezuelans to vote for Maduro should he be forced from the presidency. Chavez never gave another speech.

Even before Chavez died, Maduro had begun to fire off incendiary accusations against Venezuelan leaders, the press and the United States. Just before Chavez’s death, he went on national television and implied that the United States was behind Chavez’s cancer, having “infected” him.

To a State Department official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the delicate nature of relations with Venezuela, Maduro’s speech was consistent with how Chavez managed relations with Washington. “And in that respect,” the official said, “it wasn’t very encouraging.”

It also wasn’t very encouraging to Venezuelans in the opposition or the large segment of the population that pollsters say are tired of the political sectarianism in Venezuela.

Maduro has railed against the “rancid oligarchy,” accused Capriles of plotting against the government and warned of hazy destabilization efforts. He also has stressed repeatedly that he is an accidental president with no designs on power and that, as such, will closely follow Chavez’s guiding principles.

“I swear, in the name of the most absolute loyalty to commander Hugo Chavez, that we will obey the constitution, with a firm hand of a people who are free. I swear!” he said at the inauguration Friday.

Javier Corrales, a Venezuela expert at Amherst College, said that like Chavez, Maduro is finding that blaming others can pay off politically, particularly as serious economic problems mount.

“He has discovered, as Chavez did, that seeking to be in the extreme of the ideological spectrum is his safest spot to avoid attacks from the left, provoke the opposition and transform the political arena into a shouting match,” Corrales said.

Many observers — among them government opponents and those in Chavez’s movement — say that Maduro appears to be trying hard to appeal to the masses who liked the former president’s rhetoric while ensuring that “Chavismo” holds together.

But there are pitfalls, namely that he may not sound authentic to some, particularly if problems such as rampant crime, inflation, food shortages and a dysfunctional economy grow worse.

“He’s trying hard to copy him,” said Carlos Berrizbeitia, an opposition lawmaker. “But he doesn’t have the same tone, because he doesn’t have the same discourse and charisma that Chavez did.”

This week, many rank-and-file Chavistas — dressed in red, their eyes red from crying — spoke on the street of how they would continue to follow the directions of their dead leader. And all of them remember how Chavez had told them in his last public comments to support Maduro.

“Of course I’ll do as El Comandante told us to do,” said Maria Andrade, 54. “So if the elections were tomorrow, well, I’m sure that all the Venezuelans would be in the street going to vote for Maduro.”

Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.