BAR ELIAS, Lebanon — Most of the 12,000 or so Syrians who sought sanctuary in this little Lebanese town seeped rather than swarmed across the border — a family here, another there — taking shelter where they could, in abandoned buildings or on plots of wasteland, until one day the community woke up and realized it had a crisis on its hands.

BAR ELIAS, Lebanon — Most of the 12,000 or so Syrians who sought sanctuary in this little Lebanese town seeped rather than swarmed across the border — a family here, another there — taking shelter where they could, in abandoned buildings or on plots of wasteland, until one day the community woke up and realized it had a crisis on its hands.

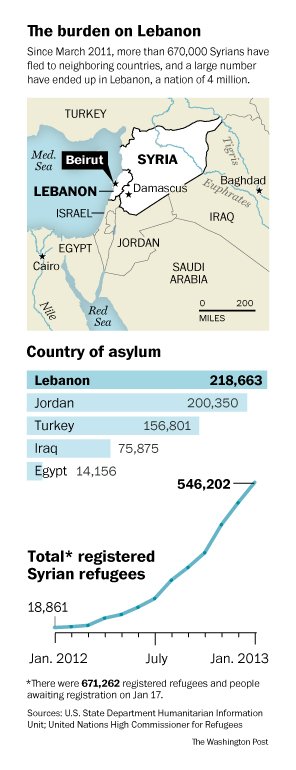

Likewise Lebanon, likewise Jordan, Turkey and, to a lesser degree, Iraq, all of them neighbors of the calamity unfolding in Syria, which is bleeding lives at the rate of more than 100 a day and refugees in excess of 100,000 a month.

The rate of departures has accelerated sharply in recent days, with nearly 50,000 Syrians fleeing the violence and reporting their presence to the United Nations in neighboring countries over the past week. With the total number of refugees estimated at more than 670,000 and no end in sight to the bloodshed, last month’s U.N. forecast that there would be more than 1 million refugees by June is on track to be surpassed well before that, according to Panos Moumtzis, regional coordinator for Syria at the UNHCR, the U.N. refugee agency.

“This is the fastest-deteriorating humanitarian crisis on the planet . . . and it is deteriorating at a much, much faster pace than we had planned for,” Moumtzis said. “It’s dramatic, it’s explosive, and it’s dangerous.”

“This is the fastest-deteriorating humanitarian crisis on the planet . . . and it is deteriorating at a much, much faster pace than we had planned for,” Moumtzis said. “It’s dramatic, it’s explosive, and it’s dangerous.”

Most can expect little in the way of assistance because the international community has yet to respond to the reality that the most violent and intractable of the Arab Spring revolts also is spawning a humanitarian catastrophe.

A U.N. appeal last month for a record $1.5 billion to aid needy Syrians inside and outside the country has drawn few pledges. Of that amount, $519 million is intended for Syrians living inside the country, where conditions were described Tuesday as “appalling” by a U.N. mission that returned to Beirut from a four-day visit to Syria.

The rest is designated for the region, where governments are increasingly overwhelmed by the influx of desperate Syrians into communities that often are poor and politically unstable — a particular challenge during winter, when plunging temperatures bring storms and snow.

With little fanfare, tiny, fragile Lebanon has emerged at the epicenter of the refugee crisis, both in terms of absolute numbers and the per capita burden they impose. More than 218,000 Syrians have registered with authorities in this nation of 4 million, according to the United Nations, more than in Turkey or Jordan, which are bigger.

The real total is almost certainly higher, because many middle-class and wealthy Syrians who don’t seek U.N. help also have joined the exodus, squeezing Beirut’s rental market, crowding its schools and worsening its traffic jams.

But the vast majority of the refugees are poor, from battlegrounds nearby in the hard-hit provinces of Homs and Damascus. As Turkey restricts the flow across its borders because its refugee camps are swamped, and the Syrian government intensifies attacks nationwide, refugees are coming from farther afield as well.

Many say they fled in an instant, running for their lives from airstrikes and shells, with little other than the clothes they were wearing.

“A bomb hit our house, and everything crashed down,” said Umm Abdullah, 44, describing how her home in northern Idlib province was demolished during an airstrike last month. She now lives with her five children in a draughty, unfinished building on the edge of the Bekaa Valley town of Bar Elias, where the nighttime temperatures drop below zero and snow lies on the ground.

“We don’t have anything. We just left as we are,” she said. “It was terrifying.”

A life as a refugee, with its indignity and uncertainty, is a last resort. After his house south of Damascus crumbled around him when hit by a shell in November, Abu Ahmed, 52, moved twice to other neighborhoods. But shellfire drove him out of those areas, too.

“There isn’t a single place in Syria you can feel safe anymore,” he said as he, his wife and his mother joined the throngs of people crossing the border into Lebanon last week.

“There isn’t a single place in Syria you can feel safe anymore,” he said

‘We have a lot of debates’

For reasons of history and politics, Lebanon is also perhaps the least equipped of Syria’s neighbors to deal with a burgeoning refugee population. Lebanon’s fraught sectarian balance, roughly divided between Christians, Sunnis and Shiites, is at risk of being disrupted by the mostly Sunni newcomers. Memories are raw of the influx of Sunni Palestinian refugees after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 and the role their presence played in triggering the 1975-90 civil war.

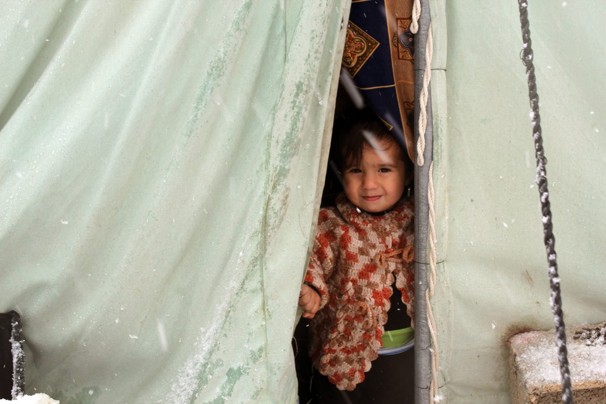

Alone among Syria’s neighbors, Lebanon has refused to allow the construction of refugee camps that may become permanent, as the Palestinian ones have. The setting up of tents is outlawed, though some refugees have pitched their own out of desperation.

Moreover, Lebanon’s Hezbollah-aligned government backs the Syrian regime, further complicating the effort to help the refugees, who tend to come from communities that support the uprising. There has been no official Lebanese help for them, and some Christian politicians have called for Syrian refugees to be barred entry, earning the wrath of Sunnis who sympathize with the rebel cause.

“We have a lot of debates, and there are a lot of conflicts,” said Social Affairs Minister Wael Abu Faour, describing the tensions within the government. “Some people want to deny there is anything going on in Syria, and they think by doing this they are supporting the Syrian regime. But, now, I think they are convinced that we can’t ignore this anymore.”

The government has drawn up a plan to help the refugees and has appealed to the international community for $180 million to fund it. Soon it is also likely to be forced to bow to the inevitability of allowing camps, said Faour, who has long campaigned for greater government assistance for the refugees. The appeal will be promoted at a U.N. conference in Kuwait on Jan. 30, at which the United Nations also hopes to secure pledges for its wider effort.

Fending for themselves

Meanwhile, the refugees in Lebanon are left largely to fend for themselves, finding whatever shelter they can and relying on the generosity of local communities. Bar Elias, seven miles east of the Syrian border, has seen its population swell by nearly a third in recent months as the refugees drift into the first town they find, sending prices and rents soaring, Mayor Naji al-Mayis said .

“It’s more than a crisis. It’s a tragedy,” he said. “The number of refugees is increasing rapidly, especially these days, to the point where we can’t provide them with their basic needs anymore.”

“It’s more than a crisis. It’s a tragedy,” he said. “The number of refugees is increasing rapidly, especially these days, to the point where we can’t provide them with their basic needs anymore.”

Conditions are bleak. Abu Hussam, his wife and his six children are living in two rooms in a half-finished building on the edge of Bar Elias. The floor is sodden. The children have colds. But there is gratitude, too, for safety and the stillness of nights without war.

“This is the most miserable life that there could be, except that there are no missiles,” said Umm Hussam, his wife, recounting the nightly bombardments the family members endured in Idlib until a shell ripped the roof off their house and they decided to run.

“There we couldn’t even close our eyes,” she said. “At least here we can sleep. Thank God.”

Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.