Pope Benedict XVI visits Lebanon Sept. 14-16, arriving in the Middle East region at a time of bloody internal conflict in Syria and simmering tensions between Israel and Iran.

Pope Benedict XVI visits Lebanon Sept. 14-16, arriving in the Middle East region at a time of bloody internal conflict in Syria and simmering tensions between Israel and Iran.

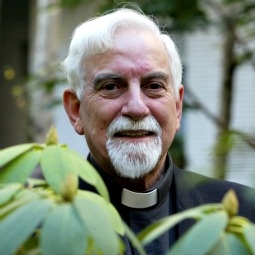

The main aim of the apostolic voyage is to present his apostolic exhortation (concluding document) on the Synod for the Middle East that took place in 2010. In a Sept. 3 interview, the respected Egyptian scholar Jesuit Father Samir Khalil Samir discussed the Holy Father’s upcoming trip, what to expect from it, and the likely consequences for Christians of the “Arab Spring” of political revolution that spread through the region last year.

A professor of philosophy, theology and Islamic studies, Father Samir is based at St. Joseph University in Beirut and also teaches at the Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome.

Is it right and wise for the Pope to travel now to Lebanon?

Is it right and wise for the Pope to travel now to Lebanon?

There is a risk. I don’t think anything would be organized against him, although we could have someone foolish acting against him. But I find it important — the fact that he so far hasn’t changed his mind.

He said he is coming, and this is also important, because it says: “I am with you. You are also living in a poor, insecure situation, and I’m taking part in your problems.”

The Lebanese government may tell him that they cannot control the situation if something happens, but from his side, he is not cancelling the trip. And this is for us — Christians and Muslims — a good sign.

Do you think that, in view of the “Arab Spring” and the current situation in the Middle East, this visit couldn’t really come at a better time?

Yes, we need this reassurance: for him to say to the world there is something more important than war and violence.

Is there a danger, in your view, that the current conflict in neighboring Syria could spill over into Lebanon while he’s there?

I think we’re used to having in Lebanon some local problems. In the last months, it was usually between Sunni and Shia. It could happen, because it’s also becoming part of a conflict in the whole area, but not really in Lebanon. We have people from both sides here also — and refugees from Syria. Something could happen, but I don’t think this will change the whole situation.

How important is it that the apostolic exhortation be delivered now? Is it more relevant, given the current circumstances?

Yes, the synod, which took place in October 2010, had important issues for Christians: because it was for Christians, particularly for Catholics, but also for relations between Christians and Muslims and the social and political situation.

It’s important for us to rethink our mission. Do we have a mission? Are we conscious of this mission, and what exactly is our mission?

People are leaving the country, but if we reflect, only in some countries there is danger, for example, in Palestine and Iraq. But in Lebanon there is no reason for a Christian to leave. Even in Egypt, there are problems and discrimination, but no real reasons to leave Egypt. And there is no discrimination in Jordan and not even in Syria.

So the first point to make is to remain here because we have a mission, and we need to find this mission together. It’s a mission of dialogue with Muslims and also announcing the Gospel to Muslims and living it in such a way.

Muslims have a right to know the Gospel. When they are convinced of their faith, they think we Christians have the right to know the Quran. In this sense, I think we only, as Arab Christians, could say something to Muslims that can be passed to both their and our culture.

A second point, one that is internal to the Church, is reform in the Church. The Catholic Church in the Middle East is a little bit too clerical. The role of the laypeople is very important here because they can say something on social, political problems, and we have no other voice. They have real dialogue every day with Muslims, but if we do it through the bishops or the patriarch, then it remains at this theoretical level.

It’s important that lay Christians understand their responsibility towards the state; it’s more important than in Europe, where people are of a Christian culture, if not of the faith.

This high level of pluralism and democracy is already practiced in Lebanon?

Yes, but not in other countries. The Pope’s trip is to Lebanon, but it’s really for the whole Middle East. He has chosen Lebanon for obvious reasons: because it has a strong Christian minority, almost 40%; the “infrastructure” of the Catholic Church is the only one to permit such a visit; and also because of the openness of the Muslims in Lebanon towards these questions.

Ecumenically, it’s very important as well, to tell the Orthodox that, yes, there are slight differences between us, but also nothing really fundamental and that we want to work together.

Lastly, between Muslims and Christians, we have problems; we are fighting in a Muslim world for more liberty of conscience, which is practically unknown. But we are doing so not only for us, but for Muslims themselves. They have a right to think independently of imams..

How likely is it that any Muslims, even extremists Muslims, will go along with that?

Extreme Muslims — Salafists — don’t agree with anything, not even with Al Azhar [University in Cairo, which is the chief center of Arabic literature and Islamic learning in the world]. They have their line; they want a caliphate, Islamic law … so, for them, dialogue is almost impossible, also between Muslims and Muslims.

Who understands the important role of Christians in Muslim societies? Christians throughout history, particularly in the Middles Ages, but also in the 20th century, were the motor behind the renewal of structures. They introduced more democracy, more openness in diplomacy, more social work and services; in education, there was a total renewal of Arabic thought. This is well known.

Is the problem with the “Arab Spring” that the number of extremists are increasing, becoming the majority?

I don’t think so. A majority of people voted for the Islamists, but it does not mean that a majority is in favor of the Islamists; it means that there was no party stronger than theirs, simply because the youth who started the revolution were divided in tens of parties and were not politically organised and unified.

Take the example of Tunisia, which was a very secular country and where Christians are almost inexistent. Nevertheless, Islamists took power because of their political organisation. The same happened in Egypt, reinforced by the large illiteracy of the population.

In Syria, I’m not so sure. Islamists are trying to take power, but the secular segment of Syria is still stronger.

Do you foresee reform in the Middle East?

I think people in the Arab world really want a change, not a change in religion, but a change in the authoritarianism of their religion, against the extremism.

Al Azhar published three documents last year saying Islam means moderation, a religion of the “just middle.” It was against the two movements, the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists. They can win now, but for how long?

So we have, as Christians, to take a longer view, to look not only at the next two years. The movement is heading in the direction of more democracy, liberty and equality between men and women, between Muslims and non-Muslims and so on. But it will take some time, maybe some decades.

So you believe the Arab spring will be a good thing in the long run?

Yes, I think so. It’s now very disappointing for everyone including me, but thinking it over, it’s [Christians’] fault: We were not able to organize ourselves in political way. Let’s give the Muslim Brotherhood a chance. They are not worse than the others, but we don’t want to fall into religious dictatorial system. If they are really able to help countries socially, to helping people have enough to eat and have jobs, and helping the country in education, in implementing a wise diplomacy, and in having good relations with everyone, not starting wars, etc., then why not? If this is the Muslim Brotherhood, then I’m in favor of them. The main point is to accept politically that the fact that they have the majority does not mean they have the right to decide alone. The majority means that your opinion is stronger, but you have to take account of the minority, especially when the minority is not a small one.

Regarding the Pope’s trip overall, are you optimistic about its effects? Do you think it could be a great success?

I don’t think it’ll be a visible success. … I think it will be very nice — people in Lebanon are happy when they meet a religious personality, certainly. The question is how we will react. If we take this apostolic exhortation as merely a paper, and, okay, some bishops read it, this will be a failure. But if we say: This is a guideline, a program, with some suggestions, and we sit together, Christians and Muslims, and see what is good for us, what is applicable and how to apply this or that point, it will be successful.

NC register

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.