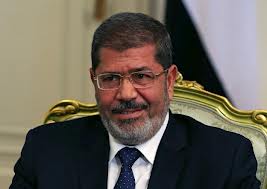

Staking out a new leadership role for Egypt in the shaken landscape of the Arab uprisings, President Mohamed Morsi is reaching out to Iran and other regional powers in an initiative to halt the escalating violence in Syria.

Staking out a new leadership role for Egypt in the shaken landscape of the Arab uprisings, President Mohamed Morsi is reaching out to Iran and other regional powers in an initiative to halt the escalating violence in Syria.

The initiative, centered on a committee of four that also includes Turkey and Saudi Arabia, is the first foreign policy priority taken up by Mr. Morsi, the Islamist who became Egypt’s first elected leader two months ago.

Following failed efforts by the Arab League and United Nations to stop Syria’s descent into civil war, Mr. Morsi’s plan sets a notably assertive and independent course for an Egypt that is still sorting out its own transition.

“We are determined to make this committee of four successful,” Yasser Ali, a spokesman for Mr. Morsi, said Sunday. He called the Syria crisis the main issue in the Egyptian president’s coming visit to China, which along with Iran and Russia has been a pillar of support for President Bashar al-Assad of Syria as his military assaulted opposition strongholds. “Part of the mission is in China, part of the mission is in Russia and part of the mission is in Iran,” Mr. Ali said.

Coming at a moment of acute hand-wringing in the Western capitals over how an Islamist leadership of the largest Arab state might alter the American-backed regional order, Mr. Morsi’s focus bisects Washington’s customary division of the region, between Western-friendly states like Egypt and Saudi Arabia on the one hand and Iran on the other, said Emad Shahin, a political scientist at the American University in Cairo.

But although it involves collaboration with American rivals, Mr. Morsi’s specific initiative, in particular, also appears largely harmonious with the stated Western objective of ending the Syrian bloodshed.

“This is a reconfiguration of the regional and international politics of the region,” Mr. Shahin said. “It will, of course, raise concerns in Washington and Tel Aviv, but I don’t think this is a confrontational foreign policy. It is a regional foreign policy, tacking a regional problem through the capitals of the four most influential regional states, without looking through the prism of Washington and Tel Aviv.”

Mr. Morsi has already called for Mr. Assad to leave power and end the bloodshed in Syria. The escalating violence there has taken on all the trappings of a proxy war that threatens to destabilize the entire region, with Iran among the main backers of the Assad government and Saudi Arabia and Turkey among the main backers of the rebels.

Despite the failure of the Arab League and United Nations initiatives in Syria, some analysts argued that Mr. Morsi’s regional approach may have a better chance to broker a peace, in part because of the mutual hostility between Iran and the West.

“Obviously, you need channels to the Assad regime — people who are uncomfortable with the way things stand and would like to be seen as playing a more positive role,” said Peter Harling, a Syria researcher at the International Crisis Group, speaking of Iran. “And any effort to reach Iran can’t include the Western camp; it would be impossible if the U.S. was involved.”

The Egyptian foreign minister had already contacted his counterparts in the other three countries to arrange a preliminary meeting, Amr Roshdy, a Foreign Ministry spokesman, said Sunday. Mr. Morsi first proposed the initiative this month at a meeting of Muslim nations in Mecca, and Iranian state news media has reported that Iranian officials have publicly lauded the plan.

Mr. Morsi is visiting Tehran this week to attend a meeting of an organization of so-called nonaligned states, but his spokesman, Mr. Ali, said the visit would last only a few hours, without any bilateral talks. He also dismissed speculation that Mr. Morsi planned to upgrade Egypt’s relations with Iran to full diplomatic relations. The two countries cut off relations after the 1979 Iranian revolution, and each keeps only a lesser diplomatic outpost in the other’s capital rather than a full embassy, even though most other Arab states — even Saudi Arabia, Iran’s longtime rival — have restored full ties.

Still, Mr. Ali called the inclusion of Iran in the regional contact group on Syria “an opportunity, because Iran is an active party in the Syrian issue.”

“Iran could be part of the solution rather than part of the problem,” he said. “If you want to solve a problem, you have to gather all the parties that have a real influence on the problem.”

The unorthodox combination of players in the proposed working group is a measure of the changing dynamics within the region. Mr. Morsi comes from the Muslim Brotherhood, a pan-Arab Islamist movement that has long been opposed to Saudi Arabia’s Western-friendly monarchy, which has outlawed the group as subversive.

Both Egypt and Saudi Arabia have been fierce rivals of Iran. And while Iran has provided military and logistics support to the Assad government, both Turkey and Saudi Arabia have helped arm the rebels trying to bring it down.

Mr. Morsi, though, may be well positioned to bring together the working group, analysts said. Egypt has credibility as “an emerging player in the Arab world and a somewhat successful model of a democratic transition in the Arab Spring,” said Mr. Harling of the International Crisis Group.

He argued that Mr. Morsi’s connections through the Muslim Brotherhood to its militant Palestinian offshoot Hamas might facilitate negotiations because of Hamas’s deep ties inside Syria. Hamas kept a headquarters in Damascus until the uprising and maintains close ties with parts of the Syrian opposition as well as some within the Assad government.

Mr. Morsi’s spokesman, Mr. Ali, stressed that the new president intended to make independence and openness the hallmarks of Egyptian foreign policy. “Egyptian diplomacy will be more active, more vibrant,” he said. “We have gone through a very long period of diplomatic stagnation, torpidity and rigidity.” He added: “We’re not counted in any axis or any old groupings. Therefore, our minds are open for everyone, and our hands are extended to everyone.”

Still, Mr. Ali also made clear that at the moment Mr. Morsi was urgently concerned with the task of reviving Egypt’s moribund economy, and that could constrain its independence.

He has said he hopes to sustain Egypt’s military partnership with the United States, which provides Egypt $1.3 billion in annual military aid.

Egypt has in recent months received $3 billion in loans from Saudi Arabia and Qatar. It is seeking a $4.8 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund. And the United States is in talks over the delivery of more than $1 billion in promised aid.

After the subject of Syria, Mr. Ali said that seeking more foreign investment would be the “second element” of Mr. Morsi’s trip to China. As a gateway to Africa and the most populous Arab state, Egypt could be a trade depot for goods from China or a regional center of industry.

But, he said, Mr. Morsi would also be working on redefining Egypt’s international role to befit its historical status as a regional leader.

“We’re not competing with anyone and we don’t seek to form alliances, but we’re pursuing a real role for Egypt that it deserves,” he said. “Because it’s not a small country, whether in terms of geopolitics, or in terms of its population and demographics and the expertise. This is what’s meant by redefining Egypt’s regional role and national security.”

NY Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.