YABRUD, SYRIA — The flag of the revolution flies high above this prosperous town in southwestern Syria. Each week, thousands take to the streets to demonstrate peacefully. Rebels roam freely — but without weapons.

YABRUD, SYRIA — The flag of the revolution flies high above this prosperous town in southwestern Syria. Each week, thousands take to the streets to demonstrate peacefully. Rebels roam freely — but without weapons.

The government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has lost control of Yabrud. But unlike Homs, Hama and countless other places where pro-Assad forces have unleashed furious assaults to keep their grip amid a 16-month-long rebellion, Yabrud appears to have been given up to the rebels. Here, at least for the time being, the revolution has been won. And it was won without a fight.

Aside from a brief foray into town in late December, the army has yet to attempt to occupy Yabrud. “They came here for a few days, but then they simply left. There was no significant battle,” said Abu Mohammed, an anti-government activist who asked that his full name not be used.

The result is an oasis of calm amid a conflict that the International Committee of the Red Cross formally declared a civil war on Sunday, one that has claimed at least 14,000 lives. It is a place that speaks to the limits of Assad’s power to control this nationwide rebellion, as well as the hopes of activists who believe the uprising can achieve its goals without dragging the country even deeper into strife.

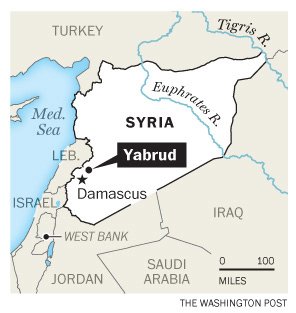

Yabrud’s idyllic farms and bustling urban life stand in stark contrast to much of the rest of the country, where war has become a daily reality. Sixty miles to the north, the city of Homs has been the site of some of the fiercest fighting, leaving entire neighborhoods destroyed by tank and artillery fire. The Damascus suburb of Douma, 30 miles to the south, has become a flash point in the battle to control the capital.

In areas that fall under the rebels’ sway, the pattern of pro-Assad forces has been to storm the town, expel anti-government fighters and go door to door, taking revenge. But not in Yabrud — at least not yet.

“It is simple,” said a local rebel commander, a defected artillery lieutenant from the Syrian army. “The army is fighting in Homs and in Damascus. They do not have the strength to also fight in Yabrud.”

The rebels don’t want a fight here, either, and have gone to great lengths to avoid one.

Abu Mohammed, the activist, credits Yabrud’s calm to a more restrained approach to revolution than that displayed by other Syrian cities. When a pro-government militia known as the shabiha has periodically caused trouble in Yabrud, the response has been deliberately muted.

“They broke into many houses, my father’s house, stealing and breaking things. We did not react strongly,” he said. “We did not want to bring the war here.”

When a prominent Yabrud-based activist was arrested two months ago, the rebel Free Syrian Army, known as the FSA, responded by kidnapping a general’s son and quietly negotiated a prisoner exchange.

FSA forces do not openly carry weapons within Yabrud, only at the rebel checkpoints that ring the town. “We didn’t want to upset the people in the town, make them afraid,” Abu Mohammed said. “Life here in Yabrud is normal.”

FSA forces do not openly carry weapons within Yabrud, only at the rebel checkpoints that ring the town. “We didn’t want to upset the people in the town, make them afraid,” Abu Mohammed said. “Life here in Yabrud is normal.”

Yabrud is a wealthy town. Most families have at least one member working abroad in the Persian Gulf, often as an engineer. Porsches and Mercedeses roll through the streets. Many citizens regularly travel to Damascus for school or business.

As a result, activists and rebel army members here are cautious. Many wear masks. Others ask that their faces not be shown in photographs. “We have had less destruction here because we have been more discreet,” Abu Mohammed said. “For instance, there is still a government police station here. All of our civil records are kept there. We don’t bother them, and they don’t bother us.”But there is nothing discreet about the 40-foot revolutionary flag flying from a cellphone tower atop a hill above town, or the weekly demonstrations on Fridays that draw thousands. Intricate revolutionary artwork covers the courtyard walls of most public buildings, and a sculpture of the FSA emblem sits on a pedestal in the town center.

Part of the town’s calm may be due to its geography. Nestled in a narrow valley, the high surrounding hills prevent the use of direct tank-cannon fire, a common government method for suppressing rebel activity.

But forgoing a fight in Yabrud also provides tactical advantages to both sides.

For the rebels, Yabrud offers a trauma center that can treat fighters wounded in nearby Homs who otherwise would not survive. Ammunition and other materiel from nearby Lebanon flows through the town and south to Damascus.

The government, meanwhile, gets a safety valve for its growing humanitarian crisis. Yabrud’s estimated pre-rebellion population of 50,000 is thought to have nearly doubled as a result of displaced Syrians who have fled from violence in Homs, Qusair and other flash points. Three of the town’s public schools serve as ad hoc refugee camps. Many Yabrudis shelter refugees in their homes or allow them to use the town’s outlying farms.

The government derives another advantage from ignoring Yabrud. The town lies near the main highway running from Damascus through Homs and on to Aleppo in the country’s north. The road is a vital government supply line. By staying out of Yabrud, the army has avoided the emergence here of a dedicated and competent rebel fighting force, such as the well-organized and well-funded Farouq Brigade that operates in Homs and increasingly in Damascus.

Most of the FSA in Yabrud consists of untrained civilians rather than defected Syrian soldiers. And although they occasionally attempt to ambush government convoys traveling the highway, such attacks are limited, rare and deliberately staged at least 12 miles farther south.

The government’s treatment of Yabrud may also be the result of a careful political calculation. The town is home to an estimated 3,000 Christians, or 6 percent of the pre-rebellion population. Its main church, the Church of Constantine and Helen, was built as a Roman temple to Jupiter. Christians and Muslims intermingle freely, and relations between followers of the two religions are warm.

Nationwide, the government has attempted to exploit apprehensions among Christians about their minority status in a Muslim-dominated post-Assad Syria. Residents speculate that Yabrud has been bypassed by the government to bolster that narrative and discourage more Christian involvement in the rebellion.

“The regime wants us to fear Muslims, but I don’t fear my brothers,” said one Christian resident who gave his name as Justin.

On the outskirts of the town one recent evening, the music of mandolins and drums wafted through the cool air. In a small farmhouse, a band of musicians lingered well into the morning hours, playing and drinking arak, the Arab version of sambuca.

A mandolin player volunteered his hope for the future. “Right now, the regime makes the people poor, so they work only for money. So art does not flourish now,” he said. “But after the revolution, our minds will free everything that is inside of us.”

But driving home later in the darkness, Abu Mohammad seemed troubled.

“I have this feeling, like the army will come here in the next few days. I have not felt this way before.” He drove on for a long, silent moment. “I hope it is nothing.”

Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.