By Paul Cruickshank

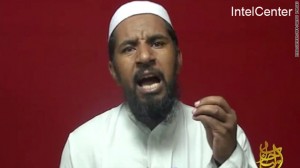

Abu Yahya al-Libi is universally admired in jihadist circles and among the younger generation of al Qaeda leaders. Charismatic, intelligent, a religious scholar – and with the extra qualification of having escaped from U.S. custody in Afghanistan – his loss is “a cataclysmic blow” to al Qaeda, according to analysts who follow the group.

Al-Libi was the target of a U.S. drone strike this week, a U.S. official tells CNN’s Barbara Starr. A U.S. official told CNN’s Pam Benson that al-Libi is dead.

In recent years, al-Libi emerged as one of the terrorist network’s most important clerics and propagandists, appearing in countless videos. By most accounts, he was effectively al Qaeda’s deputy leader. And his Libyan nationality is important to an organization that after the elevation of Ayman al-Zawahiri as leader was vulnerable to criticism it was dominated by Egyptians.

Noman Benotman, a former senior member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) who spent significant time with al-Libi in the 1990s, told CNN that his death is a “very serious blow” to al Qaeda because no one else within the group rivals his legitimacy as a religious scholar nor has the credibility in the Arab world to provide Islamic justifications for al Qaeda’s global campaign of terrorism.

“Awlaki wasn’t even close,” said Benotman, referring to Yemeni-American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, who was killed in a drone strike in Yemen last year.

Al-Libi (real name: Hasan Muhamad Qayed) was born in Marzaq in the southwest Sabha province deep inside Libya’s interior. As a young man he studied chemistry for one year at Sabha University but, like many young Libyans, was swept up in an Islamic awakening hostile to the Gadhafi regime that arose in Libya in the late 1980s.

As an outlet for their frustration, and a chance to participate in Holy War, al-Libi and his brother, Abd al-Wahab al-Qayed (also subsequently known as Idris), were among the many young Libyans who traveled to Afghanistan to fight jihad against the Soviet-backed government. In 1990 his brother was one of the founding members of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, which fought a failed campaign to overthrow the rule of Moammar Gadhafi in the mid 1990s.

Benotman, who is now a senior analyst at the Quilliam Foundation in London, first spent time with al-Libi around 1990-1991 in Afghanistan. He recalls that al-Libi was always much more interested in religious learning than fighting.

“He was a very smart guy and hungry to learn about Sharia law,” Benotman told CNN.

After a few years in Afghanistan, al-Libi traveled to Mauretania, where he undertook religious studies for two years under well-known scholars, according to Benotman. “He was the best student they had,” Benotman said.

Benotman noticed the change in al-Libi when he returned to Afghanistan: “He was a real and serious Sharia student.” In the mid-1990s al-Libi moved to Sudan with other LIFG fighters after conditions for Arab fighters became difficult in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region. Separately, Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda also relocated there. Benotman said that al-Libi took no operational role in the coordination of a insurgent campaign the group began against the Gadhafi in Libya around this time.

“He didn’t have fighting skills or knowledge of military leadership,” Benotman told CNN.

After the Taliban took over much of Afghanistan in 1996, al-Libi settled in Kabul, according to Benotman. Al-Libi’s religious views leaned toward the extreme, said Benotman, but he did not subscribe to the ultra-hardline “takfiri” interpretation of Islam that argued for the permissibility of killing those regarded by some Sunnis as “heretical” Muslims – like the Shia.

In late 2001, al-Libi’s world was turned upside down when the United States routed the Taliban in Afghanistan. Like many Arab fighters he fled across the border to Pakistan, where he holed up in an apartment block with other militants in Karachi, according to Benotman.

But a Pakistani raid in 2002 led to his arrest and he was quickly handed over to American authorities, who held him in a prison in Kandahar, according to Benotman. He was subsequently transferred to an American detention facility at Bagram air base near Kabul.

It was al-Libi’s escape from the prison in July 2005 that shot him to jihadist stardom. His nighttime escape was featured in a subsequent jihadist propaganda video narrated by a fellow escapee, who claimed that as American soldiers patrolled it was al-Libi who cut a wire mesh fence, allowing them to escape and eventually connect with the Taliban fighters in Kabul.

Al-Libi himself appeared in the video in which he alleged the Americans were responsible for severe human rights violations, claiming that when a new prisoner arrived, he would be abused and humilated until “he almost loses his mind.”

After some time in hiding in Afghanistan, al-Libi traveled to the tribal areas of Pakistan, which were increasingly becoming a new safe haven for Arab fighters and al Qaeda operatives. His views on jihad were increasingly in line with the terrorist group. In December 2006 he appeared in a video urging jihadists to learn how to make nuclear weapons.

Al-Libi became one of al Qaeda’s chief ideologues and propagandists, appearing in numerous recruitment videos in which he cast himself as a sheikh with the legitimacy to issue fatwas.

His eloquent Arabic addresses, several of which were made to groups of fighters sitting crossed-legged outdoors in the tribal areas of Pakistan, were filmed and disseminated online, and won him a significant audience among a radical fringe of young Muslims in the Arab world.

Part of al-Libi’s appeal to young Muslims radicalized by the Iraq war was his uncompromising ideology. But there were limits to his radicalism. According to Benotman he was concerned about the negative fallout of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s barbaric campaign in Iraq.

In 2008 al-Zawahiri cited a tract written by the Libyan to justify al Qaeda’s campaign of terrorism. The tract was titled “Human Shields in Modern Jihad.” According to Jarret Brachman, an American academic who has long studied al Qaeda, al-Libi argued that al Qaeda could take on the West only if it engaged “in a fierce war using weapons of mass destruction” and that this would entail Muslim casualties.

As drone strikes began to take their toll on al Qaeda in 2008, killing a number of senior leaders, al-Libi appeared to play a more hands-on military role in the organization despite his lack of combat experience.

Bryant Neal Vinas, a young American from Long Island who was recruited into al Qaeda, testified in a recent court case that during the late summer of 2008 he participated in an expedition to attack a U.S. base near the Afghanistan-Pakistan border with a group of fighters under the command of al-Libi, whom he described as the “emir” of an al Qaeda outfit based in Lwara, Pakistan, near the Afghan border.

Benotman said that al-Libi’s military role should not be exaggerated. “He’s not a frontline fighter or someone very capable of military strategy,” he told CNN.

Brachman and other counterterrorism analysts came to see al-Libi as a natural successor to bin Laden because of his charisma and religious credentials. In an interview with CNN in 2009, Benotman was sceptical al-Libi would be effective in the top job: “He lacks the management skills of a bin Laden; the ability to see the big picture and think strategically. Hardcore Salafists don’t think practically because they believe God will help them through.”

By the second half of 2010, as more senior al Qaeda operatives were killed or captured, al-Libi was thrust into a managerial role. But within the al Qaeda hierarchy he was still junior to another Libyan within the group.

Letters recovered from bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad suggest al-Libi developed a working relationship with Atiyah abd al-Rahman, who in mid-2010 took over al Qaeda’s day-to-day operations in the tribal areas of Pakistan and became bin Laden’s main interlocutor within the terrorist organization until al-Rahman’s death in a drone strike in August 2011.

Al-Rahman was known as a strategic thinker but also a pragmatist. In December 2010 he and al-Libi wrote a joint letter to Hakimullah Mehsud, the leader of the Pakistani Taliban, to scold him for the group’s indiscriminate killing of Muslim civilians and use of kidnapping, which they said was hurting the jihadist cause in Pakistan. A copy of the letter was subsequently found in Abbottabad.

After the death of al-Rahman, counterterrorism officials believe, al-Libi stepped into his shoes in managing the day-to-day operations of the terrorist network and its relations with affiliates.

Benotman says that like al-Rahman, al-Libi had significant influence with al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), al Qaeda’s North African affiliate, and Al-Shabaab, the network’s Somali affiliate. “They respect him, love him, and listen to him,” Benotman told CNN. His loss might therefore damage al-Zawahiri’s ability to coax the affiliates into following his strategic guidance.

After the onset of the Arab Spring in 2011, al-Libi took a lead role in al Qaeda’s propaganda efforts to try to turn events to their advantage.

Benotman said that it is here and in his justification of al Qaeda’s global campaign of attacks that his loss would be most keenly felt. The Libyan cleric was able to describe the stakes arising from the Arab uprising in religious terms more effectively than any other al Qaeda leader, according to Benotman.

Addressing Libyan followers in a wide-ranging video address in December 2011, al-Libi said, “At this crossroads you have found yourselves, you either choose a secular regime that pleases the greedy crocodiles of the West and for them to use it as a means to fulfill their goals, or you take a strong position and establish the religion of Allah.”

With his death, it is possible there may be a backlash by pro al Qaeda forces in Libya. According to several sources, al Qaeda has developed a presence in eastern Libya, where it has recruited and trained several hundred fighters. Last month a previously unknown jihadist outfit calling itself the Imprisoned Omar Abdel Rahman Brigades claimed responsibility for a rocket attack on the Red Cross in Benghazi.

Al-Libi, in a video released late last year, claimed his own death would not hurt al Qaeda’s cause:

“I say to America: Don’t have hopes that you are about to defeat al Qaeda. Let al Qaeda be defeated and all their leaders and individuals be killed, and then what? The battle with America today is not with an organization or a group or a sect, but it is a battle with the Ummah of Islam,” meaning the global Islamic community.

CNN

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.