Egypt’s presidential election was supposed to be the grand payoff of a popular revolt that pitted a despotic statesman against an unlikely coalition of citizens, suddenly unafraid.

But on the eve of a landmark vote that will determine former president Hosni Mubarak’s successor, the mood across Egypt is nowhere near as electrifying and upbeat as it was in the days after the autocrat’s ouster on Feb. 11, 2011.

As they begin slipping ballots into boxes Wednesday in what is widely expected to be the country’s first free and fair presidential vote, some Egyptians have been left feeling underwhelmed, if not bitter. The results could widen rifts that have strained the country’s social fabric during the turbulent post-revolutionary period.

Polling data are seen as unreliable, making the outcome difficult to predict. But the race is shaping up as a contest between Egyptians who want to be led by an Islamist and those who favor a secular statesman, even though the front-runners who fit that description have ties to Mubarak’s regime.

Polling data are seen as unreliable, making the outcome difficult to predict. But the race is shaping up as a contest between Egyptians who want to be led by an Islamist and those who favor a secular statesman, even though the front-runners who fit that description have ties to Mubarak’s regime.

No candidate is predicting fraud on the scale that for decades ensured overwhelming victories for Mubarak’s National Democratic Party, but voters and politicians have voiced concerns about potential tampering or other irregularities.

Fewer foreign monitors were credentialed to observe this week’s balloting than were permitted for parliamentary elections that began in November. Those who did get permission received their accreditation badges at the last minute, prompting complaints that they would not have enough time to prepare.

Already two candidates have lodged complaints about alleged fraud during voting abroad last week that put the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohammed Morsi in the lead.

Meanwhile, state television — which gets its editorial guidance from the generals who have ruled the country since Mubarak’s exit — has in recent weeks ramped up flattering coverage of Ahmed Shafiq, Mubarak’s last prime minister. His rallies have been divisive, with anti-Shafiq protesters at least once throwing shoes at the candidate and, in several other instances, getting into rock-throwing brawls with his supporters.

The ruling generals had pledged to turn over power to a civilian government by June 30, but it remains unclear whether they will meet that deadline and how completely they will cede control. A new constitution has not been written, and the generals had been expected to announce the powers of the presidency before voting began but faced a huge backlash and failed to do so.

Unprecedented campaign

The campaign season that formally kicked off April 30 has been extraordinary for a nation that was governed by the autocratic Mubarak for nearly three decades. The 13 presidential candidates have crisscrossed Egypt holding rallies that have inspired popular fervor, passionate debate and some violence.

At a cafe in the working-class district of Imbaba in the capital, Hamdi Sayed, 62, drank tea with his childhood friend Sayed Abdel Fatah, 64, under a poster of Shafiq. Both described themselves as eager first-time voters.

“We never, never, never voted, and maybe 99 percent of the people didn’t vote and Mubarak would get 99 percent of the vote,” Sayed said, laughing. “Everyone is free to choose now, and at the end of this we want a respectable president to fulfill the demands of the people.”

The race is being debated openly and loudly on street corners, in living rooms and online. The Twitter hashtag #candidatedomesticfights, which Egyptians have used to describe divided households, has drawn scores of messages.

“A friend’s sister threathend to leave her husbend when he wanted to vote for shafiq. Now he won’t,” tweeted Mahmoud Salem, a well-known blogger.

Shafiq is one of five front-runners who analysts say could be among the two top finishers after a first round of voting Wednesday and Thursday. Unless one candidate receives more than 50 percent of the vote — a highly unlikely prospect — the top two candidates are scheduled to face off in a second round next month.

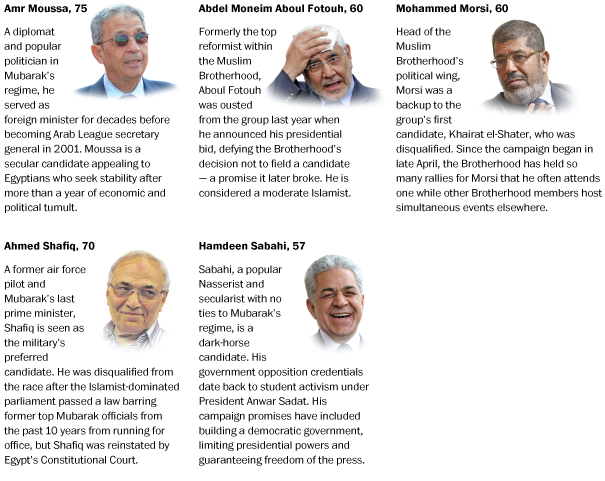

The other Mubarak-era candidate that enjoys widespread support is Amr Moussa, a former foreign minister and chief of the Arab League. Revolutionaries disparage both for being “remnants” of the ousted regime. Moussa says he distanced himself considerably from the former president when he left his post as foreign minister more than 10 years ago.

Hamdeen Sabahi, a longtime Arab nationalist in the tradition of Gamal Abdel Nasser, who led Egypt’s 1952 revolution and military coup, is the only secular candidate with no links to Mubarak’s government. He has seen his candidacy gain traction in recent weeks, mostly from young revolutionaries who do not want an Islamist or a Mubarak-era figure, but he remains a dark horse in the race.

The leading Islamist candidates are Morsi, of the Muslim Brotherhood, whose political party dominates parliament, and Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, a former Brotherhood leader who broke ranks with the group to launch his candidacy. Morsi is backed by the Brotherhood’s powerful political network but is less charismatic than the group’s first choice for the job, Khairat el-Shater, who was later disqualified. Aboul Fotouh has attracted a wide range of supporters, including secular revolutionaries, liberals and ultraconservative Muslims known as Salafists.

“We are dealing with an election where we might see five candidates with double-digit numbers,” said Michael Wahid Hanna, an Egypt expert at the Century Foundation. “No one knows which way this will go.”

Voter reservations

“I’m afraid more than excited,” said Ahmed Imam, 28, a manager of a clothing store in central Cairo. “I’m afraid that something might happen — violence, or anything like that.”

Imam said that he plans to vote for Sabahi and that he “hopes that nobody tampers” with his ballot. “Everyone should vote,” he said.

But not everyone will. Among those who plan to boycott the vote is Salah Abdel Masoud, a carpenter and painter who said he has had no work since last year’s revolt. He voted for the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice party in parliamentary elections but complained that he has seen little progress.

“All my educated kids are sitting at home, and I sit all day in a coffee shop with no work,” the 64-year-old said. “What is this election?”

In Tahrir Square, the symbolic heart of last year’s revolt, there is little campaign fever. Most of the activists who once maintained a round-the-clock presence, demanding that the military chiefs give up power, have vanished.

Inside one of the few tents that remain, activist Khalid el-Abedi, 46, said none of the front-runners on the ballot espouse the values of the revolution.

“None of those figures have the kind of character to lead Egypt,” he said on a recent afternoon.

This weekend, a prominent work of graffiti in Tahrir that superimposed the face of ruling general Mohammed Hussein Tantawi over Mubarak’s was covered over with white paint. Graffiti artists went to work overnight to bring it back, and now it includes the images of Moussa and Shafiq.

“I will never trust you and you will not rule me another day,” the graffiti artist wrote next to the new creation.

Washington Post

Presidential election front runners

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.