Williamsport, Pennsylvania, used to be celebrated for its past — as the 1938 birthplace of Little League Baseball, which still plays its annual World Series nearby. Then natural gas was found.

Williamsport, Pennsylvania, used to be celebrated for its past — as the 1938 birthplace of Little League Baseball, which still plays its annual World Series nearby. Then natural gas was found.

Now this once-sleepy chunk of north-central Pennsylvania is a star on the map of an emerging national energy rush. Six hotels are new or being built, and about 100 companies have moved to town, sometimes so fast that the head of the local Chamber of Commerce has told executives wanting guided tours to wait.

“I’ve said, ‘Look sir, get in line,’ ” says Vince Matteo, chief executive of the Williamsport/Lycoming chamber. “Now I know people in their 20s with high school (diplomas) making $120,000 a year.”

Much of Wall Street and Washington is seized by the hope that the U.S.‘s energy future will be as bright as Williamsport’s. As Americans heave a sigh of relief at gasoline prices falling back from near $4 a gallon, big new discoveries of domestic oil and natural gas hold the promise of more substantial benefits for the U.S. economy for decades to come — even the possibility of energy independence.

Every president since Richard Nixon has called for the U.S. to wean itself from needing oil from unstable or unsavory countries. The nation’s new-found energy riches are likely to bring that ambition closer to reality in the next two decades, according to many forecasters.

It’s no pipe dream. The U.S. is already the world’s fastest-growing oil and natural gas producer. Counting the output from Canada and Mexico, North America is “the new Middle East,” Citigroup analysts declare in a recent report.

The U.S. Energy Information Agency says U.S. oil imports will drop 20% by 2025. Oil giant BP projects the U.S. will get 94% of its energy domestically by 2030, up from 77% now, as oil imports fall by half. Energy billionaire T. Boone Pickens, a major investor in oil and natural-gas companies, said the U.S. can at least end oil imports from Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, about half its total, through new drilling and by shifting diesel-swilling trucks to natural gas. Any other oil needs should be from politically stable allies such as Canada, Pickens said.

Most enticing, a team of analysts and economists at Citigroup argues that the U.S., or at least North America, can achieve energy independence by 2020, as more domestic production and doubling down on conservation produce a virtuous cycle. The U.S. can make itself a net exporter of crude oil, refined products and natural gas — says Citigroup energy strategist Seth Kleinman.

“The notion of the U.S. getting to zero net imports of oil is obviously a sexy notion, but it’s not necessary for it to mean the world will change,” he says. “We are seeing a dramatic collapse in U.S. net imports of oil as we speak, to the tune of almost 1 million barrels a day each year over the last four years.”

If anything like that happens, an improbable-sounding litany of good things can result.

In practical terms, more energy independence could mean 3.6 million new jobs, enough to cut unemployment by two percentage points, Citigroup argues. It could help manufacturers and chemical businesses that use lots of energy or make products from natural gas. It might give the U.S. a structural advantage on trade partners in energy costs, helping to offset the edge that cheaper labor gives nations such as China, Kleinman says. Already, U.S. natural gas prices are a seventh of what they are in Beijing, Pickens says.

“The potential is clearly there for a genuine revitalization and reindustrialization of the economy,” Kleinman says. “In industries where energy is a major element of costs, the U.S. is moving into a uniquely advantaged position.”

After years of gripes that the U.S. imports too much oil, the energy industry is pumping a gusher of good-news numbers:

•The U.S. price of natural gas has plummeted more than 80% since 2008, including nearly 45% in the last year, thanks to new supplies. The falling cost of natural gas alone will save U.S. households $926 a year between now and 2015, consulting firm IHS Global Insight says.

•The USA’s 15% gain in crude-oil production since 2008 is by far the world’s biggest, with new fields just beginning to be developed. The U.S. has overtaken Russia as the world’s largest refined-petroleum exporter, according to Citigroup.

•Utilities’ switchover to cheap natural gas from coal is lowering power bills. One utility switching to more gas plants, Georgia Power, has filed to cut Atlanta-area electricity rates 6%, citing a 19% drop in fuel costs.

Drill and conserve

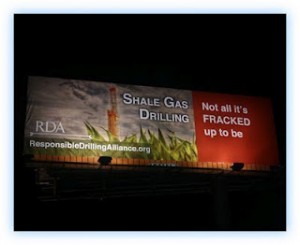

A dozen years after Texas wildcatter George Mitchell commercialized a new gas-drilling technology called hydraulic fracking, the new energy boom is taking off. It began with gas, as fields such as the Marcellus Shale in the Northeast and the Barnett Shale in Texas began producing gas that hadn’t been recoverable until Mitchell combined fracking — which uses chemicals, water and sand to force gas out of rock — with horizontal drilling, which yielded much more than simply drilling straight down.

More recently, the same technologies have been adapted to drill for oil. Oil fields are being developed from Pennsylvania to Alaska — a half-dozen or more major sites, each including many smaller ones.

The rush to oil from gas is now so fast that Devon Energy, the No. 3 independent oil-and-gas-driller, isn’t drilling a single new gas well this year, CEO John Richels says.

Because of fracking, Citi says U.S. oil production might climb more than a third by 2015, driven by “tight oil” from shale and tar sands that until recently was too costly to extract. Government estimates say domestic production will rise 22% by 2020 to 6.7 million barrels per day. At the same time, the 19 million barrels that Americans burn daily may fall by 2 million, by Citi’s numbers. One reason: The EIA says the U.S. will be 42% more energy-efficient by 2035, continuing an enduring trend.

One reason for all that new efficiency is regulation.

Automakers face federal corporate-average fuel economy standards doubling, to up to 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025. A 2007 law requires oil companies to quadruple production of renewable auto fuels by 2022. States such as California are making utilities buy up to 60% more renewable-sourced electricity by 2020, says Stuart Hemphill, vice president for power supplies at Southern California Edison. “In California, only two kinds of (energy-producing) facilities are getting built — natural gas and solar,” Hemphill says.

Why $2 gasoline is unlikely

For consumers, America’s new energy supplies help contain costs — but they’re not a magic path back to $2 gasoline.

The good news: Natural-gas heating costs have dropped nearly 40% since 2008, undoing half their 160% climb after 1999. Electricity costs have remained flat, too.

The bad news: Gasoline prices have flirted with all-time highs this year, and even the fast-emerging new supplies are unlikely to offer major relief soon.

To understand why, it helps to master some numbers.

First is the number two — the U.S. has two main energy markets, one each for electricity and transportation. They’re very different. Electric utilities use mostly coal, natural gas and nuclear power, or renewables, almost all from the U.S. and Canada. Cars use oil, about 45% of it imported.

The second big number is 86 — the 86 million barrels of crude produced worldwide daily. About 19 million are burned in the U.S., three-fourths of them for transportation, the government says. About 8.9 million are imported, 4.2 million from OPEC. Bringing crude-oil imports down will be about changing how Americans fill gas tanks — or whatever advanced electric-car battery replaces gas tanks.

Domestic natural-gas gluts will do little for real energy independence until more cars use electricity or natural gas, says Hemphill. That’s one reason Pickens is campaigning to subsidize converting business truck fleets to natural gas — legislation the Senate defeated in March.

“I’m for anything American,” Pickens said. “I want at least to get off the 5 million barrels a day we get from OPEC.”

The most important number may be $70 — the estimated cost to produce a barrel of oil from shale or tar sands, the heart of the new U.S. supplies. While natural-gas prices have sunk, oil prices might not, since they typically follow the cost of producing the most expensive barrel on the market.

Today’s world oil prices of about $111 a barrel are boosted by tensions from Iran’s nuclear program, as well as emerging-market oil demand that will exceed that of developed nations for the first time this year, according to the International Energy Agency. At about $95 a barrel, U.S. oil prices have risen, too, even though the U.S. doesn’t import Iranian crude.

Using the rule of thumb from research firm IHS CERA, that a $10 move in crude changes U.S. gasoline prices by 24 cents a gallon, dropping crude to $70 would lower pump prices about $1, leaving gasoline near $3.

Broad economic impact

Even so, all this new energy is creating jobs across the country. North Dakota, now the nation’s fourth-largest oil producing state, boasts a 3% unemployment rate, the nation’s lowest. In Williamsport, the local economy grew 7.8% in 2010, making it one of the nation’s fastest-growing metro areas.

Projections for energy-related jobs vary, but are all pretty large. More than two-thirds of Citi’s estimated 3.6 million new jobs will come from multiplier effects, as the 550,000 new workers in fossil fuel-related jobs spend their incomes, or as other Americans spend the money they save from cheaper energy, Citi says. IHS Global Insight says the natural-gas boom alone has created 600,000 jobs and will rise to 1.6 million by 2025.

The money saved on energy will pay dividends throughout the economy. Lowering the $400 billion the U.S. sends abroad annually for oil would function like a huge tax cut, says Chris Lafakis, energy economist at Moody’s Analytics.

“A third to 40% would be my guess” at how much the U.S. can cut imports by the next decade, Lafakis says. “At 40%, that’s $160 billion a year, and that’s massive. It’s like the temporary payroll tax cut we have now, plus a third, and it lasts forever.”

A less statistical way to reckon all this is to look at Williamsport.

“It put people to work who hadn’t worked in a long time,” Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Corbettsays. “It was a natural-gas rush that put demand on housing, on stores, on restaurants.”

Watching for exaggerations

Yet many hopes — and fears — about the U.S. energy boom will likely prove exaggerated.

Citi’s thesis that gas and oil will stay cheaper in the U.S. than abroad, for example, assumes most exports of U.S. crude remain illegal and natural-gas exports stay rare, says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. Instead, U.S. crude is likely to be refined into exportable products such as gasoline, while infrastructure to export liquefied natural gas improves. Both will pull U.S. prices toward higher world levels, he says.

“Markets have a wonderful way of finding their way around restrictions when there’s money to be made,” Zandi says.

Williamsport exemplifies the likeliest impact of all. With natural-gas prices so low, drilling has all but halted. But gas companies are using the lull to build pipelines, as drilling action moves to oil patches in Western Pennsylvania.

In the meantime, some spinoff industries are coming into focus. Shell has announced plans to build a cracking plant, which will make chemicals from natural gas, outside Pittsburgh. The expected payoff includes 10,000 construction jobs, Corbett says. All this is part of turning the short-term energy boom into a long-term economic plan, he says.

While short-term booms wax and wane, hope persists that the new oil and gas means a better future for Williamsport, and for America.

“They tell us not to worry,” the Chamber’s Matteo says. “The gas isn’t going anywhere and neither are they.”

USA today

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.