Syria’s remaining cash reserves are quickly dwindling as the country’s anti-government uprising marks its 13th month, according to intelligence officials and financial analysts who describe a steady hollowing-out of the country’s economy in the face of sanctions.

Syria’s remaining cash reserves are quickly dwindling as the country’s anti-government uprising marks its 13th month, according to intelligence officials and financial analysts who describe a steady hollowing-out of the country’s economy in the face of sanctions.

The financial hemorrhaging has forced Syrian officials to stop providing education, health care and other essential services in some parts of the country, and has prompted the government to seek more help from Iran to prop up the country’s sagging currency, the analysts said. Revenue from Syrian oil, meanwhile, has almost dried up, with even China and India declining to accept the nation’s crude, they said.

At the same time, President Bashar al-Assad appears to have shielded himself and his inner circle from much of the pain of the sanctions and trade embargoes, which are driving up food and fuel prices for many of the country’s 20 million residents, U.S. and Middle Eastern analysts and financial experts say. Assad’s reserves and sizable black-market income are probably sufficient to keep the regime’s elite in power for several months and perhaps longer, intelligence officials and outside experts said.

The government is not expected to have trouble funding its military operations anytime soon.

“The economic pressure is severe, but unfortunately it’s not yet enough,” said a Middle Eastern intelligence official whose government closely monitors economic trends in Syria. The official, like several others interviewed, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive intelligence on Syria’s economy.

The assessments of Syria’s fiscal deterioration come amid new efforts by Western governments to tighten the financial noose around the nation, which faces increasing economic and political isolation after brutally repressing anti-government activists for more than a year.

The European Union on Monday adopted measures prohibiting the sale of luxury goods to Syria, and the Obama administration ordered sanctions against individuals or firms that provide Assad with surveillance equipment and other technology that could be used to stifle dissent.

The new strictures are among more than a dozen rounds of sanctions since the start of the uprising in March 2011, and more are expected next month when representatives of as many as 75 countries gather in Washington to coordinate efforts to shut down Syria’s remaining revenue streams.

Defense Secretary Leon E. Panetta, in testimony to U.S. lawmakers last week, said that the sanctions are “undermining the financial lifeline of the regime,” cutting government income by nearly a third.

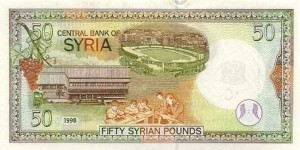

Western officials stress that the sanctions and an earlier embargo against Syrian oil imports are intended to target the country’s government and business elite, rather than ordinary people. But the measures have fueled a succession of fiscal shocks that are being felt across the Syrian economy, so far without directly endangering Assad’s 12-year rule, analysts say. These include not only a jump in consumer prices but a sharp drop in the value of the Syrian pound. Wages have stayed stagnant.

Western officials stress that the sanctions and an earlier embargo against Syrian oil imports are intended to target the country’s government and business elite, rather than ordinary people. But the measures have fueled a succession of fiscal shocks that are being felt across the Syrian economy, so far without directly endangering Assad’s 12-year rule, analysts say. These include not only a jump in consumer prices but a sharp drop in the value of the Syrian pound. Wages have stayed stagnant.

A cash cushion estimated at $20 billion a year ago has plunged to between $5 billion and $10 billion and now loses about $1 billion a month

‘Flying through cash’

More ominous for Assad’s survival is the depletion of what was once a mountain of hard currency in the government’s bank accounts. A cash cushion estimated at $20 billion a year ago has plunged to between $5 billion and $10 billion and now loses about $1 billion a month, according to Middle Eastern and Western intelligence officials with access to intelligence assessments of Syria’s economy. U.S. officials separately confirmed that Syria’s reserves have dropped by more than half since the start of the uprising.

“They are flying through cash in order to finance the crackdown, and they have no prospects for getting more,” said a senior Obama administration official briefed on the latest intelligence.

The official described oil-laden tankers stuck indefinitely in Syrian waters, unable to find foreign buyers because of embargoes. Even Syrian efforts to sell oil through Iranian intermediaries have failed, the official said, because sanctions have prompted maritime insurance companies to drop coverage for Syrian and Iranian vessels.

“The hope,” the official said, “is that Assad not only will be unable to finance his crackdown, but the pressure will permeate in other ways,” driving a wedge between him and the country’s military and business elites.

“The hope,” the official said, “is that Assad not only will be unable to finance his crackdown, but the pressure will permeate in other ways,” driving a wedge between him and the country’s military and business elites.

The emptying of the government’s coffers — combined with fears of a further drop in the value of the Syrian pound — has prompted Syrian officials to repeatedly call on Iran, their closest foreign ally, to help stabilize their currency, the officials said.

“Iranian money is helping Assad survive,” said a second Middle Eastern intelligence official. “But Iran is having its own problems, and they are more limited now in the support they can offer.”

Syria’s fiscal unraveling stems not only from the loss of oil revenue but also from the collapse of its vital tourist industry, economic analysts say. In addition, economic sanctions on banks have hobbled the country’s import businesses, which no longer get the vital letters of credit from banks that serve as guarantees in import deals. The International Monetary Fund estimated a 2 percent contraction in the economy last year.

As exports have dwindled along with tourist bookings, the flow of foreign currency into the country has ebbed, causing the value of the Syrian pound against the dollar to plummet. An exchange rate of about 50 Syrian pounds to a dollar a year ago plunged last month to more than 100 pounds per dollar on the Syrian black market. With intervention from Syrian banks, the pound recovered on the black market to about 70 to the dollar, still well below pre-uprising levels.

Crackdown stays steady

The financial weakening has notably failed to slacken the government’s resolve to crush the uprising, analysts note. Activists reported heavy fighting in the countryside around the central city of Hama this week, and images posted on rebel Web sites showed U.N. monitors in the heavily damaged Mashaa al-Arbaeen area of the city walking among piles of rubble.

An exchange rate of about 50 Syrian pounds to a dollar a year ago plunged last month to more than 100 pounds per dollar on the Syrian black market.

On Tuesday, Kofi Annan, who is serving as the joint U.N.-Arab League envoy for Syria, delivered a carefully worded briefing to the U.N. Security Council that both raised concern about the government’s conduct in recent weeks and urged the council to maintain support for his fragile diplomatic bid.

“Our patience has been tested severely — close to its limits,” he said, according to notes taken by a council diplomat. “But we have also seen signs that there is the possibility for the parties to implement a cessation of violence, which can lead to a political process and peaceful way out of the crisis.”

Syrian state media on Tuesday reported a car bombing in the al-Marjeh area of Damascus and said two members of the security forces were killed by armed groups in the suburbs of the city. As a rule, such reports cannot be verified because Syria restricts journalists’ access.

Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.