She was in her kitchen making tea for her brother’s family, who was visiting her at her home in the Iraqi capital Baghdad, when gunfire broke out in the sitting room.

“It was as if there was a war in my home,” she recounted.

She could not move; could not breathe; could not do anything. Militias killed nine members of her family that day, while she stood in the other room, effectively paralysed.

Those were the early days of sectarian warfare in Iraq. Tens of thousands of other deaths would follow over the course of the next two years.

Samia told IRIN her story years later from the rural suburbs of the Syrian capital, Damascus, where she now lives as a refugee with her husband and two of her children.

She is desperate to get out of Syria, where she says she continues to receive threats from across the border in Iraq.

“Until now, I get calls saying if you come back, we will kill you,” she said.

The current unrest in Syria has only made things worse – food prices have risen, she is reliving memories of war, and worst of all, her family’s resettlement in the USA has been indefinitely stalled, with limited alternatives for leaving Syria if the situation there continues to deteriorate.

“I try to manage, scraping a bit from here, a bit from there to make ends. Only God knows how much I’m suffering,” she said.

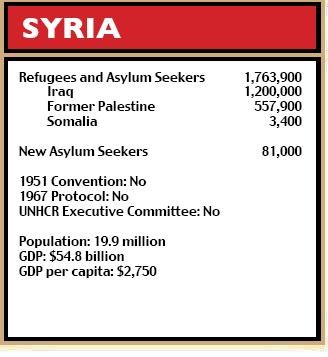

While the world focuses on the tens of thousands of Syrian refugees fleeing an increasingly violent conflict between the government and opposition forces, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis in Syria – the largest Iraqi refugee population in the world – have been all but forgotten. The 102,000 registered refugees, amid a government estimate of 1 million Iraqis in total, now face a more uncertain future than ever – and some of them are crying out for help.

“Please,” Samia begged this IRIN reporter, “Consider me your mother. Do something to help me. Let our voices reach America…Why can’t they just take us out of here?”

Flight from Syria

Until now, there has been no mass departure of Iraqi refugees from Syria. But according to government figures, in 2011, 67,000 Iraqis in Syria returned to an Iraq which, while significantly safer than in 2006-7, is still one of the most dangerous places in the world. That number is a significant jump from previous years: In 2009 and 2010 combined, the number of returns from Syria was less than half that, according to statistics recorded by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the Iraqi Ministry of Displacement and Migration.

One senior aid worker told IRIN most of these returns have been willing, voluntary and ultimately “the best solution”.

But the Brookings Institution, calls their return “premature” and a survey by UNHCR just before the unrest in Syria started found that most refugees in Syria were still unwilling to return home permanently.

“In situations like this, often, refugees have to decide between two difficult situations and they will have to decide which is the least problematic,” Panos Moumtzis, UNHCR’s newly-appointed regional coordinator for the Syria crisis, told IRIN last month.

Much smaller numbers of Iraqis in Syria have fled a second time – into Turkey, and to a lesser extent Lebanon and Jordan, where entry poses some challenges.

Struggling to survive economically

Most Iraqis in Syria live in Damascus and the business capital, Aleppo, relatively unaffected by the violence in Syria, which has killed an estimated 9,000 Syrians since March 2011. Thus “they have continued to enjoy relative stability and peace,” Moumtzis said.

Until now, UNHCR has been able to continue its regular assistance programmes for Iraqi refugees, even in places as far as Hassakah, in the northeast.

But the devaluation of the Syrian currency, sanctions and a deepening economic crisis in Syria have affected everyone, including refugees who were economically vulnerable to begin with and who are forbidden from legal work as refugees in Syria.

The vast majority of the Iraqi refugee population in Syria gets food assistance, which UNHCR says has helped to stave off negative coping mechanisms and keep malnutrition at bay, but refugees say they are eating less and even selling food to make ends meet.

Mohamed*, an Iraqi refugee in the northern Syrian city of Halab, receives 10,500 Syrian pounds a month (about $183) for his family of seven as a food allowance from UNHCR; but the bill for rent, water and electricity is higher. And as food and gas prices have more than doubled in some cases, his family has been forced to change their eating habits, eating one loaf of bread per day instead of two, for example.

His family depends on remittances – now affected by the devaluation of the Syrian currency – from family in Iraq to survive. UNHCR recently increased the food allowance from 1,100 to 1,500 pounds per person per month ($19 to $26); and intends to increase cash assistance for the most vulnerable by 40 percent to compensate for the increase in prices.

She is desperate to get out of Syria, where she says she continues to receive threats from across the border in Iraq.

“Until now, I get calls saying if you come back, we will kill you,” she said.

Samia, in rural Damascus, says her family sells the food they receive from the World Food Programme in order to pay rent and carry them over until the end of the month.

“I try to manage, scraping a bit from here, a bit from there to make ends. Only God knows how much I’m suffering,” she said.

Her daughter has lost significant weight, she said, and the family has reduced its food intake to basics like bread, tomatoes and oil, refraining from fruit, chicken, cheese and other perceived luxuries.

Forbidden from formal employment in Syria, most Iraqis work in the informal sector – in hotels or in tourism – an industry hard-hit by the unrest. During a UNHCR survey of more than 800 refugees in February, 40 percent of respondents reported a decrease in their monthly income, and 13 percent had lost their employment altogether, Helene Daubelcour, UNHCR spokesperson in Syria, told IRIN. Ninety percent of them said they had higher food expenditures.

Their secondary displacement has also driven up rent prices, as the pressure on the availability of accommodation increase.

“You see the domino effect,” Daubelcour said.

At a roundtable discussion hosted by the Brookings-LSE Project on Internal Displacement and the International Rescue Committee in February, participants pointed to tensions between Iraqi refugees and displaced Syrians as they compete for diminishing resources.

Re-traumatization

More than direct violence, refugees in Syria are at risk of re-traumatization, with 78 percent of refugees surveyed by UNHCR saying the current situation had had a negative impact on their mental and physical well-being, including nightmares and recollections of the past. The anxiety has led to an increase in domestic violence, Daubelcour said.

“We feel that what happened in Iraq could happen again,” said Mohamed, who says he was kidnapped and tortured by the Mahdi Army, a Shia militant group, in May 2006.

“I’m afraid of everything around me,” said Samia, the Iraqi who was in the other room when her family was killed.

“We feel that what happened in Iraq could happen again,” said Mohamed, who says he was kidnapped and tortured by the Mahdi Army, a Shia militant group, in May 2006.

In response, UNHCR has further developed its psychosocial support and counselling.

Of the 1,600 Iraqis from Syria who registered with UNHCR in Turkey, most said they did not feel safe.

“[They said] they already went through this once in Iraq and they have no intention whatsoever of waiting for it to hit them more particularly,” one senior aid worker in Turkey told IRIN. “It seems to be that they are leaving pre-emptively.”

Stuck in Syria

The problem is that many of them cannot do so.

Some 18,000 Iraqi refugees who had already been accepted for resettlement to a third country or were awaiting interviews, have had their files frozen. Initially delayed due to new US security procedures, the cases have now been put on indefinite hold because resettlement countries have had more difficulty conducting interviews amid the unrest.

Both Samia and Mohamed’s families have had their suitcases ready for months, believing they were to travel any day; others were reportedly turned back at the airport. They are now “stuck” in Syria until a solution is found.

“There are a lot who had the expectation of resettlement and will not be resettled any time soon,” said Andrew Harper, UNHCR representative in Jordan.

Refugee advocates have called for completing the process by video conference, but UNHCR representatives say that option, as well as the possibility of processing them in another country, is simply not manageable for such a large number of people.

“Frankly speaking,” said the aid worker based in Turkey, “I don’t think it is realistically doable.”

Nor would it necessarily be welcomed in neighbouring countries, which are themselves hosting Iraqi refugees and have resettlement processes of their own.

“Whether they jump the cue or not, that’s quite a sensitive issue,” the aid worker pointed out.

This has left people like Samia and Mohamed “between a rock and no place”, as the Iraqi Refugee Assistance Project put it – unwilling to return to Iraq’s continued violence, uncomfortable with the rising insecurity and economic challenges in Syria, but unable to leave for fear of losing their chance at permanent resettlement elsewhere.

Mohamed said he was told that if he left for Jordan or Turkey, his case could be closed. UNHCR says there is no guarantee resettlement cases will be taken up at the same stage if refugees leave for another country.

“I don’t want to waste these years that I invested here and throw them away for nothing,” he told IRIN. “I spent six years here. There’s no way I’m going to start over again.”

“If we had any way of going elsewhere, we would have left,” Samia’s daughter, Zeinab*, told IRIN.

Freedom of movement

Others don’t have the financial means to leave Syria in the first place.

“If we had any way of going elsewhere, we would have left,” Samia’s daughter, Zeinab*, told IRIN.

But the doors would not necessarily be open to them. Iraqis can get a visa for Turkey at the border, and have been able to enter Lebanon on tourist visas (about 100 have done so). But Jordan, which has opened its doors to fleeing Syrians, has all but closed the border to Iraqis, observers say, out of a fear that a mass influx of Iraqis would overrun the already strained infrastructure in their small country, already hosting many Iraqis from 2003 onwards.

“Of course, there are different considerations [for Iraqis],” Jordanian government spokesperson Rakan al-Majali recently told IRIN. “There are specific rules and regulations governing the entry of Iraqis which existed before the crisis in Syria and continue to exist.

“A humanitarian situation does not justify breaking rules that apply to a specific group.”

UNHCR acknowledges that this could lead to a situation in which it becomes too violent for Iraqis to stay in Syria, too dangerous to go back to Iraq and impossible to enter Jordan. It would then be up to the international community to lobby other countries to take these refugees in.

In addition to the Iraqis, there are around half a million Palestinians and some 8,000 refugees from other countries – Somalia, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, even Afghanistan – who can’t necessarily go back to their countries of origin.

“At the moment, we would like to see the borders remain open,” regional refugee coordinator Moumtzis said. “Of course, the final decision is on the neighbouring countries to make sure that this is implemented.”

“With 45% of registered Iraqi refugees having been in Syria for over five years, and decreasing opportunities for resettlement, the character of the refugee situation will become protracted in nature,” says the response plan.

*Names changed to protect identities of refugees

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.