WHEN his heart was so hardened that the sight of blood and bodies no longer shocked him, when he could no longer follow his commander’s orders to fire on unarmed civilians, Khaled* ran.

WHEN his heart was so hardened that the sight of blood and bodies no longer shocked him, when he could no longer follow his commander’s orders to fire on unarmed civilians, Khaled* ran.

He left his Syrian Armed Forces unit – the 18th division, stationed outside Rastan in the western Syrian province of Homs – with one clear thought in his head: ”I must make it to the Free Syria Army.”

Khaled’s is a complicated, painful story, told by a thoughtful young man wise beyond his years who has unpacked the psychology of this brutal battle of Syrian against Syrian a thousand times over.

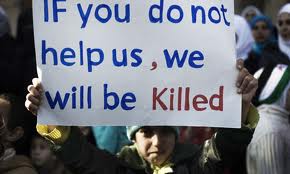

Many incidents, small and large, pushed the 25-year-old university graduate to defect from the army that stands accused of killing at least 9000 Syrians since the country’s uprising began 13 months ago. But it was the deadly aftermath of an overheard radio exchange that convinced him to trust what his head and his heart had been saying from the beginning.

”I heard my commander talking to his leader on the radio – a spy had told him there was going to be a demonstration on that day, held in an auditorium so that the army could not see them.

”He was told, ‘Shoot them all, they are all armed.”’

Khaled, who says he was not with the soldiers who followed those orders, saw the video broadcast on the internet and on news channels that night. The battalion had fired up to six mortar rounds and one landed in the crowded auditorium, killing 14 people, he said.

When the dust cleared it revealed a floor strewn with body parts.

”They were just kids,” he says quietly. ”They were not hurting anyone.”

That was March 2. By March 5, he had defected. He had made it just two months into the 11-month-long compulsory military service. Since then Khaled has barely stopped running.

”When the revolution started I was a civilian. I had been in protests myself where we had been caught and beaten up, so I knew what we were facing. But in the beginning I thought I did not have a choice, that I could not say no.

”I went into the military thinking I would not hurt anyone – that I could stop them hurting people – but the reality was very different,” Khaled says, acknowledging his naivety in a voice heavy with regret. But the haven he had been looking for with the Free Syrian Army was short-lived. Here, at least, he was no longer being asked to fire anti-aircraft guns towards crowds of protesters 1.5 kilometres away.

Yet in the 10 days he was with the FSA in Idlib, he observed a rebel army without a strong leader, willing to torture an old man on the word of an informant. ”I said to them, ‘If you do this you are no better than Assad,”’ he recalls.

”I went into the military thinking I would not hurt anyone – that I could stop them hurting people – but the reality was very different,”

His pleas fell on deaf ears, and soon he was on the move again, this time to a place just inside the Turkish border known as the ”Defectors Camp”.

When he arrived in mid-March there were 800 people, including families, living in the secure camp established for Syrian Army defectors by the Turkish government.

Located in Hatay Province, on the southern part of Turkey’s 911-kilometre border with Syria, the camp has already grown to 1600 people, Khaled says, and it is expected to grow further.

But here, too, there was little comfort.

”There was so much prejudice and hatred … against Alawites [a branch of Shiite Islam to which President Bashar al-Assad belongs],” he says. ”I am not prejudiced against Alawites.

”What is happening in Syria is becoming a civil war. I could no longer stay there.”

His journey from protester to conscript, from defector to rebel and back to defector again has been dangerous and psychologically scarring.

It has made him question his own values, and those of his fellow Syrians. It has forced him to leave his family behind in the north of Syria, cross illegally into Turkey and to try to exist without any of the support given to officially registered refugees.

”I am not thinking about whether I am safe – I just wanted to get out of that vicious cycle.”

Turkey is now home to 27,165 Syrians who have fled homes and towns that have been under almost constant bombardment from the forces of President Assad.

Parts of its southern border with Syria have also become informal bases for rebel soldiers, who collect food and other supplies in Turkey and smuggle them into Syria.

Defectors, refugees, soldiers – all are waiting to see if the fragile ceasefire negotiated by UN special envoy Kofi Annan holds.

Since it took effect on April 12, the ceasefire has been breached daily by Dr Assad’s forces, which have also accused the Free Syrian Army of breaching the agreement.

The northern province of Idlib has been the focus of ongoing government shelling. An activist in Idlib, Fadi al-Yassin, told Associated Press that shelling had killed dozens of people in recent days.

A six-member team of UN observers arrived in Damascus earlier in the week and on Tuesday travelled to Daraa, where the revolution began in March last year.

If Syria complies with the terms of the United Nations Security Council resolution that backs Mr Annan’s six-point plan, a larger UN observer mission is expected to be deployed in the coming weeks.

*Not his real name.

smh.com.au

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.