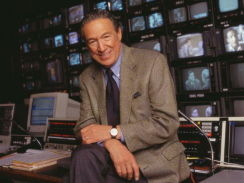

CBS News legend Mike Wallace, the 60 Minutes’ pit-bull reporter whose probing, brazen style made his name synonymous with the tough interview — a style he practically invented for television more than half a century ago — died last night. He was 93 and passed peacefully surrounded by family members at Waveny Care Center in New Canaan, Conn., where he spent the past few years. He also had a home in Manhattan.

CBS News legend Mike Wallace, the 60 Minutes’ pit-bull reporter whose probing, brazen style made his name synonymous with the tough interview — a style he practically invented for television more than half a century ago — died last night. He was 93 and passed peacefully surrounded by family members at Waveny Care Center in New Canaan, Conn., where he spent the past few years. He also had a home in Manhattan.

“It is with tremendous sadness that we mark the passing of Mike Wallace. His extraordinary contribution as a broadcaster is immeasurable and he has been a force within the television industry throughout its existence. His loss will be felt by all of us at CBS,” said Leslie Moonves, president and CEO, CBS Corporation.

“All of us at CBS News and particularly at 60 Minutes owe so much to Mike. Without him and his iconic style, there probably wouldn’t be a 60 Minutes. There simply hasn’t been another broadcast journalist with that much talent. It almost didn’t matter what stories he was covering, you just wanted to hear what he would ask next. Around CBS he was the same infectious, funny and ferocious person as he was on TV. We loved him and we will miss him very much,” said Jeff Fager, chairman CBSNews and executive producer of 60 Minutes.

A special program dedicated to Wallace will be broadcast on 60 Minutes next Sunday, April 15.

Wallace was as famous as the leaders, newsmakers and celebrities who suffered his blistering interrogations, winning awards and a reputation for digging out the hidden truth on Sunday nights in front of an audience that approached 40 million at broadcast television’s peak.

Wallace played a huge role in 60 Minutes’ rise to the top of the ratings to become the number-one program of all time, with an unprecedented 23 seasons on the Nielsen annual top 10 list — five as the number-one program.

He announced he would step down to become a “correspondent emeritus” in the spring of 2006, but Wallace continued to land big interviews for 60 Minutes. His last appearance on television, on January 6, 2008, was a sit-down on 60 Minutes with accused steroid user Roger Clemens that made front-page news. His August 2006 interview of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won him his 21st Emmy at the age of 89. He was also granted the first post-prison interview with assisted suicide advocate-and convicted killer Dr. Jack Kevorkian for a June 2007 60 Minutes broadcast. After a successful triple bypass operation in late January 2008, he retired from public life.

Decades before his 60 Minutes success, Wallace was already known to millions. In the early days of broadcasting, with no line between news and entertainment, Wallace did both in the 1940s and ’50s. He appeared on a variety of radio and television programs, first as narrator/announcer, then as a reporter, actor and program host. On his first network television news program, ABC’s “The Mike Wallace Interview,” he perfected his interviewing style that he first tried on a local New York television guest show called “Night Beat.” Created with producer Ted Yates, “Night Beat” became an instant hit that New Yorkers began referring to as “brow beat.” Wallace’s relentless questioning of his subjects proved to be a compelling alternative to the polite chit-chat practiced by early television hosts.

Years later, CBS News producer Don Hewitt remembered that hard-charging style when creating his pioneering news magazine, 60 Minutes; he picked Wallace to be a counterweight to the avuncular Harry Reasoner. On September 24, 1968, Wallace and Reasoner introduced 60 Minutes to the 10:00 PM timeslot, where it ran every other Tuesday but failed to draw large audiences. But critics praised it, awards followed, and after seven years on various nights, 60 Minutes went to 7:00 PM Sunday and began its rise. It made the top 20 in 1977 and the top 10 in 1978, then became the number-one program in 1980 — all with a tough-talking Wallace center stage.

The rising interest in Wallace and 60 Minutes grew partly out of the Watergate scandal. Wallace’s interrogations of John Erlichman, G. Gordon Liddy and H.R. Haldeman whetted the appetites of news junkies who continued to tune in to see Wallace joust with other scoundrels. Before long, he was a household name. In 1983, Coors beer took ads out in major newspapers after Wallace’s 60 Minutes investigation found little truth to rumors the company was racist. “The Four Most Dreaded Words in the English Language: Mike Wallace is Here,” ran atop ads boasting that the firm had passed muster with the “grand inquisitor” himself.

Each week, 60 Minutes viewers could expect the master interviewer to ask the questions they wanted answered by the world’s leaders and headliners. Wallace did not disappoint them, often revealing more than the public ever hoped to see. He got the stoic Ayatollah Khomeini to smile during the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979 when he asked him what he thought about being called “a lunatic” by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. The Ayatollah answered by correctly predicting that Sadat would be assassinated. The same year, Johnny Carson called Wallace “cruel” during an interview after Wallace asked, “It takes one to know one?” when the late-night star took pity on an alcoholic newsmaker. Her fans protested when Wallace brought Barbra Streisand to the emotional edge in 1991 by revealing that her own mother had told him that Barbara “was too busy to get close to anyone.” He never softened, even in his 80s. In a 2001 interview about his Broadway mega hit “The Producers,” Mel Brooks began an angry rant against anti-Semitism prompted by Wallace’s suggestion that his claims of bias were exaggerated. In 2003, he wrung tears out of one of the most feared defensive players in NFL history when he read lines to Lawrence Taylor spoken by Taylor’s son.

Wallace was also known for pioneering the “ambush” interview, presenting his unsuspecting interviewee with evidence of malfeasance — often obtained by hidden camera — then capturing the stunned reaction. Two of the more famous exposes in this genre that used hidden cameras were investigations of a phony cancer clinic and a laboratory offering Medicaid kickbacks to doctors. Presenting interviewees with their own misdeeds became a 60 Minutes staple, but the hidden camera and ambush were later shunned as they were widely imitated and even Wallace admitted their use was to “create heat, rather than light.”

Sometimes the feisty reporter was the story, getting arrested in Chicago in 1968 on the floor of the Democratic Convention and making headlines 36 years later, at the age of 86, when words with a New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission officer resulted in an arrest for disorderly conduct.

Wallace drew attention also for taking on controversial subjects. From legal prostitution at Las Vegas’ Mustang Ranch, to child pornography to gay police officers — a 1992 report that won him an Emmy — no subject was taboo. No story generated more controversy than Wallace’s 1998 interview with euthanasia practitioner Dr. Jack Kevorkian. Wallace and 60 Minutes took heat for broadcasting Kevorkian’s own tape showing him lethally injecting a man suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The death of Thomas Youk broadcast on 60 Minutes made the headlines and editorial pages, generating discussion about euthanasia for weeks. The tape also served as evidence to convict Kevorkian of murder. In another controversy, Wallace’s 1995 interview of Jeffrey Wigand, the highest-ranking tobacco executive to turn whistle-blower, was held back for fear of a multi-billion dollar lawsuit that could have bankrupted CBS. The interview, in which Wigand revealed tobacco executives knew and covered up the fact that tobacco caused disease, was eventually broadcast on 60 Minutes in February 1996. The incident became the subject of the film, “The Insider.”

Wallace was also at the center of one of the biggest libel suits ever, threatening his journalistic integrity and ultimately plunging him into a clinical depression. Gen. William Westmoreland, who commanded the U.S. military in Vietnam, sued CBS and Wallace for a 1982 “CBS Reports” documentary alleging the general had deceived the American people by under counting the enemy in Vietnam. The $120 million suit against “The Uncounted Enemy: A Vietnam Deception,” went to trial in 1984 and lasted months before Westmoreland withdrew it just before Wallace was to testify in early 1985. The grueling test became a defining moment in Wallace’s life. Medication and therapy helped him overcome his initial depression and a later relapse, and he became a heroic example to fellow sufferers, speaking publicly for the rest of his life to de-stigmatize the disorder. He revealed years later to colleague Morley Safer in a 60 Minutes special on his life that he had attempted suicide during the lawsuit crisis.

In another celebrated case that took 12 years to play out, Wallace’s producer Barry Lando was sued for $44 million by Lt. Col. Anthony Herbert. The libel suit against Wallace’s 1973 60 Minutes report, “The Selling of Colonel Herbert,” caused a precedent-setting Supreme Court ruling allowing lawyers to question the thoughts and opinions of reporters. Initially, CBS lawyers argued successfully in a New York federal appeals court that Lando could not be questioned that way as it would infringe on the editorial process protected under the First Amendment. But the Supreme Court in 1979 reversed it, ruling that Herbert was entitled to know the producer’s mindset, as it was crucial to proving malice. Nevertheless, the report was accurate in its main elements, and, in 1986, Herbert v. Lando was thrown out.

The road to 60 Minutes began for Wallace when his son, Peter, died in a hiking accident in Greece in 1962. Wallace’s jobs in broadcasting then included entertainment programs and commercials in addition to reporting, but he decided then that he would devote his career to journalism alone to honor Peter, a Yale student who aspired to a writing career. Wallace’s other son, Chris, became a journalist and is currently host of “Fox News Sunday.”

Wallace went to Vietnam, India and Africa to report for Westinghouse Radio’s “Around the World in 40 Days,” but really wanted to be hired by CBS News, the “mother church,” as he often referred to it. He was turned down at first, despite some remarkable documentary work, including a breakthrough piece on black Muslims, “The Hate that Hate Produced.” In fact, CBS News wouldn’t broadcast a documentary on nuclear proliferation that he reported because he appeared in cigarette ads. Promising to drop commercial work, he was made a correspondent at CBS News in 1963.

Starting first on “CBS Morning News With Mike Wallace,” he went on to contribute to most of the Network’s other news programs, including the “CBS Evening News With Walter Cronkite,” reporting from Vietnam, Washington and the campaign trail in 1968 with Richard Nixon – who offered Wallace the White House press secretary job. He made news at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that year by getting ejected from the proceedings for an altercation with police on the convention floor.

It wasn’t the first time Wallace had worked for CBS. He began at the Network in 1951, when he and his wife, Buff Cobb, with whom he hosted “The Chez Show” on local Chicago television, were invited to New York. He did several CBS programs, two with Cobb: “Mike and Buff,” an afternoon talk show that was television’s first color telecast, and an on-location interview program called “All Around the Town.” As was the norm then, he also reported for the news division, covering political conventions and other events.

Leaving CBS in 1955, his career through the early 1960s became a hodgepodge of appearances for the tireless broadcaster, who was seen on all three networks and several independent stations. He even starred briefly in a Broadway production of “Reclining Figure” and played himself in Elia Kazan’s celebrated film about the media, “A Face in the Crowd.” He did the TV quiz show “The Big Surprise” and the radio show “Weekday,” but he never lost sight of his true calling. It was also during this time that he began “Night Beat,” anchored the original Peabody-Award winning series “Biography,” anchored and reported several documentaries, including “The Race for Space,” and headed up the news department of local New York station WNTA. Then on channel 13, WNTA was the first television station in the U.S. to broadcast a half-hour news program; it was called “News Beat” and Wallace anchored it. He also continued “The Mike Wallace Interview” on WNTA in 1959, as the ABC Network, its previous home, dropped the program because it became too controversial.

Myron Leon Wallace was born in Brookline, Mass., on May 9, 1918. He attended Brookline High School and was graduated from the University of Michigan in 1939 with a B.A. degree in liberal arts. He became acquainted with radio at the college station and, after graduation, a professor helped him land his first job as an announcer and “rip-and-read” reporter for WOOD-WASH, a Grand Rapids, Mich. radio station.

He made his network radio debut in 1940 at WXYZ in Detroit, where he was the narrator for “The Green Hornet” and a “Cunningham News Ace,” reading the news sponsored by the Cunningham Drug store chain. He soon moved to Chicago and, by 1941, Wallace was beginning to make a name for himself as a news writer and broadcaster on “The Air Edition of the Chicago Sun.” He joined the U.S. Navy in 1943 and served aboard a submarine tender in the Pacific as a communications officer. In 1946, he returned to Chicago to resume his broadcasting career. There, on WMAQ radio, he hosted his first interview program, “Famous Names,” which led to a raft of broadcasting appearances, including his first network television appearance as the lead in a police drama, “Stand By For Crime.” The 1949 show was the first to be transmitted from Chicago to the East Coast. Two years later, Wallace joined CBS in New York, where he lived ever since.

Besides his Emmys, Wallace was the recipient of five DuPont-Columbia journalism and five Peabody Awards, and was the Paul White Award winner in 1993, the highest honor given by the Radio and Television News Directors Association. He won the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award grand prize and television first prize in 1996. In June of 1991, he was inducted into the Television Academy Hall of Fame.

Wallace authored several books, including: “Mike Wallace Asks,” a compilation of interviews from “Night Beat” and “The Mike Wallace Interview” published in 1958; his memoir, “Close Encounter,” co-authored with Gary Paul Gates, in 1984; and “Between You and Me,” also with Gates, in 2005.

Part of his rich legacy includes the Knight-Wallace Fellowship and Mike and Mary Wallace House at his alma mater, the University of Michigan. Wallace’s donations support this in-residence study program begun in 1994 for professional journalists seeking to improve their knowledge in a desired field or issue.

Wallace is survived by his wife, the former Mary Yates, his son, Chris, a stepdaughter, Pauline Dora, two stepsons, Eames and Angus Yates, seven grandchildren and four great grandchildren. At the family’s request, donations can be made in Wallace’s name to Waveny Care Center, 3 Farm Rd., New Canaan, Conn.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.