Khawam, who has spent years spray-painting Beirut’s streets, made his first piece of soldier graffiti in 2011. Though graffiti art, which is widespread in Lebanon, has never been officially outlawed, his soldier series may cost him a million Lebanese pounds (about 500 euros) or three months in prison, if the courts side with the prosecution.

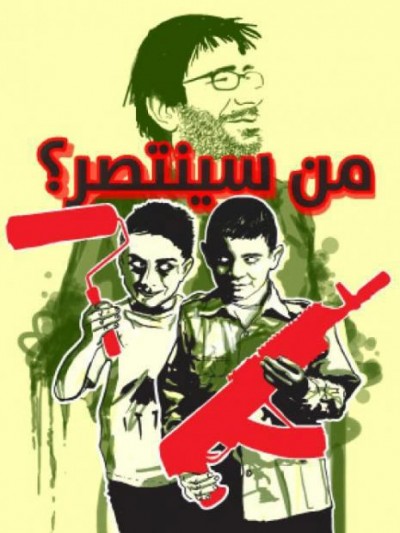

“My graffiti is about Lebanon’s civil war and soldiers, one of the country’s touchiest subjects”

In the past, Lebanese authorities have censored certain graffiti, notably messages of support for the Syrian uprising, a movement that the majority of the country’s government opposes. However, up until now, they have simply censored the messages with a coat of paint.

Khawam should be handed his verdict on June 25. In the meantime, graffiti artists from around the Arab world have expressed their support for his work.

Back in September 2011, I was spray-painting graffiti on a wall specifically dedicated to this purpose when two men from the military’s secret service came up to me. They asked me what I was painting, and I explained I was painting soldiers. They asked me to stop, and left. But moments later, as I was still working, the police came to arrest me. At the police station, they interrogated me and forced me to sign a statement promising not to do any more graffiti. Of course, I disobeyed. So they asked me to come to the police station two more times. The third time they asked, I refused to go. And then one morning, in February, I received a letter ordering me to go to court.

“The old ghosts of sectarianism are back”

The state has accused me of breaking the law, but I don’t understand which law. My lawyer’s argument is that there is no law in Lebanon that says graffiti is illegal. In fact, graffiti is all over the place in this country! Some of my friends suggested I just pay the fine so that the authorities would leave me alone, but I said no. I refuse to give in to this bullying and want to push the authorities until they admit they are censoring me.

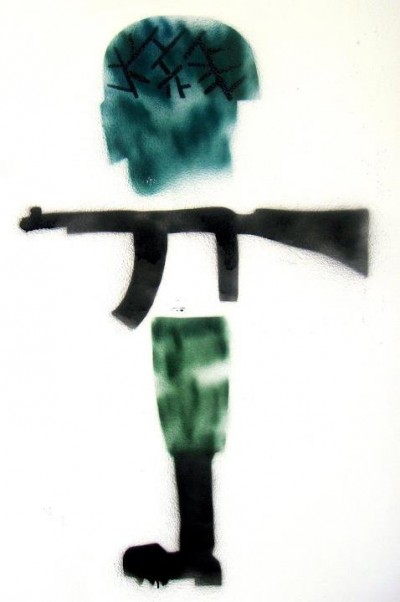

The name of my graffiti series is “Do not forget.” I painted soldiers armed with machine guns but without any other identifying details, so you can’t tell if they are Muslim or Christian. I did this to show the shared responsibility of both sides in the war.

Weapons have begun circulating again, too. Specific zones of the city are reserved for people of one faith and closed to others, such as the southern suburbs of Beirut, which are controlled by Hezbollah, and where non-Shiites cannot go. In short, people are reduced to their faith and it’s once again become impossible to simply be Lebanese.

The reason this graffiti is bothering the authorities more than the graffiti I’ve done in the past is because I’m not only taking on the touchy subject of the civil war, but I’m also talking about the army, which is a major taboo in our society. Before me, a graffiti artist named Ali had depicted police officers and written “I love corruption” next to them. His graffiti art was quickly covered up with paint. Depicting soldiers, however, draws even stronger censure from the authorities.

My case is only one among many other cases of censorship in Lebanon. Freedom of expression is a myth here, since three major taboos remain: politics, religion, and sex. This censorship is always religious in nature. Each religious community tries to impose its own values. [Lebanon’s population is 59 percent Muslim and 39 percent Christian, with a small Jewish minority population. Power is attributed based on religion: the president must be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister must be a Suuni Muslim and the head of parliament must be a Shiite Muslim].

“Freedom of expression is a myth here in Lebanon”

Our society suffers from this sectarianism. Today, it’s impossible to talk about the army, the president, Hezbollah, or the revolutions in the Arab world without running the risk of shocking one community or another. People need to understand that nothing is sacred and that we must have the right to criticise everything. However, this will only be possible in a secular state.

France 24

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.