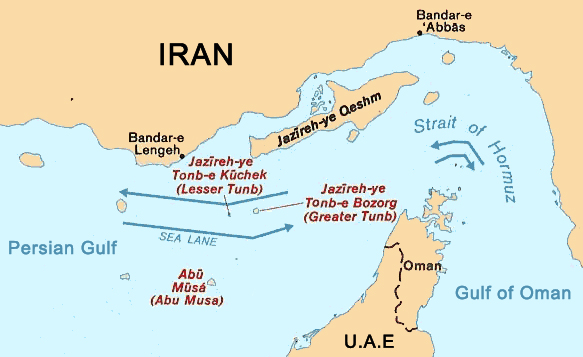

Should Iran’s rulers ever make good their threats to block the Straits of Hormuz, they could almost certainly achieve their aim within a matter of hours.

Should Iran’s rulers ever make good their threats to block the Straits of Hormuz, they could almost certainly achieve their aim within a matter of hours.

But they could also find themselves sparking a punishing — if perhaps short-lived — regional conflict from which they could emerge the primary losers.

In recent weeks, a growing number of senior Iranian military and civilian officials have warned that Tehran could use force to close the 54 km (25 mile) entrance to the Gulf if Western states impose sanctions that paralyze their oil exports.

In 10 days of highly publicized military exercises, state television showed truck-mounted missiles blasting towards international waters, fast gunboats practicing attacks and helicopters deploying divers and naval commandos.

Few believe Tehran could keep the straits closed for long — perhaps no more than a handful of days — but that alone would still temporarily block shipment of a fifth of all traded global oil, sending prices rocketing and severely denting hopes of global economic recovery.

But such action would swiftly trigger retaliation from the United States and others that could leave the Islamic republic militarily and economically crippled.

“They can cause a great deal of mischief… but it depends how much pain they are willing to accept,” says Nikolas Gvosdev, professor of national security studies at the U.S. Naval War College in Rhode Island.

He said he believed Tehran would only take such action as a last resort: “They are much more likely to threaten than to act.”

The true purpose of its recent saber-rattling, many analysts suspect, may be more a mixture of deterring foreign powers from new sanctions and distracting voters from rising domestic woes ahead of legislative elections in March.

With the United States signing new sanctions into law on New Year’s Eve — although they will not enter force until the middle of the year — and the European Union considering similar steps, few expect the pressure on Tehran to let up.

“This is probably less a genuine military threat than a bid to put economic pressure back on the West and split Western powers over sanctions that threaten Iran’s oil economy,” says Henry Wilkinson, head of intelligence and analysis at London security consultants Janusian.

“Iran now does not have much to lose by making such a threat and a lot to gain.”

But many fear the more Iran is pushed into a corner, the greater the risk of miscalculation.

Its ruling establishment is also widely seen as deeply divided, with some elements — particularly the well-equipped and hardline Revolutionary Guard — much keener on confrontation than others.

SEA MINES, MISSILES, SUBMARINES, SPEEDBOATS

“I cannot see strategic sense in closing the straits, but then I do not understand the Iranian version of the ‘rational actor’,” said one senior Western naval officer on condition of anonymity.

“(But) one can be pretty certain that they will misjudge the Western reaction… They clearly find us as hard to read as we find them.”

The capability to wreak at least temporary chaos, however, is unquestionably there.

The U.S. Fifth Fleet always keeps one or two aircraft carrier battle groups either in the Gulf or within striking distance in the Indian Ocean.

Keenly aware of conventional U.S. military dominance in the region, Iran has adopted what strategists describe as an “asymmetric” approach.

Missiles mounted on civilian trucks can be concealed around the coastline, tiny civilian dhows and fishing vessels can be used to lay mines, and midget submarines can be hidden in the shallows to launch more sophisticated “smart mines” and homing torpedoes.

Iran is also believed to have built up fleets of perhaps hundreds of small fast attack craft including tiny suicide speedboats, learning from the example of Sri Lanka’s Tamil Tiger rebels who used such methods in a war with the government.

At worst, its forces could strike simultaneously at multiple ships passing out of the Gulf, leaving a string of burning tankers and perhaps also Western warships.

But a more likely initial scenario, many experts believe, is that it would simply declare a blockade, perhaps fire warning shots at ships and announce it had laid a minefield.

“All the Iranians have to do is say they mined the straight and all tanker traffic would cease immediately,” says Jon Rosamund, head of the maritime desk at specialist publishers and consultancy IHS Jane’s.

RETALIATION, ESCALATION

U.S. and other military forces would find themselves swiftly pushed by shippers and consumers to force a route through with minesweepers and other warships — effectively daring Tehran to fire or be revealed to have made an empty threat.

During the so-called “tanker war” of the mid-1980s, Gulf waters were periodically mined as Iran and Iraq attacked each other’s oil shipments.

U.S., British and other foreign forces responded by escorting other nations’ tankers — as well as conducting limited strikes on Iranian maritime targets.

This time, retaliation could go much further. In closing the straits, Tehran would have committed an act of war and that might prove simply too tempting an opportunity for its foes to pass up.

“We might well take the opportunity to take out their entire defense system,” said veteran former U.S. intelligence official Anthony Cortesman, now Burke Chair of Strategy at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington DC.

“You’d almost certainly also see serious strikes on their nuclear facilities. Once the Iranians have initiated hostilities, there is no set level at which you have to stop escalation.”

Whilst in theory it would be possible to push heavily protected convoys through the straits even in the face of Iranian attack, few believe shippers or insurers would have the appetite for the level of casualties that could involve.

Instead, they would probably hold back until Tehran’s military had been sufficiently degraded. That, Western military officers confidently say, would only be a matter of time.

“Anti-ship cruise missiles are mobile, yet can… be found and destroyed,” said one U.S. naval officer with considerable experience in the region, speaking on condition of anonymity.

“Submarines are short-duration threats — they eventually have to come to port for resupply and when they do they will be sitting ducks.”

“DANGEROUS GAME OF CHICKEN”

Given the forces arrayed against them, many analysts believe Tehran will ultimately keep the straits open — not least to allow their own oil exports to flow — whilst finding other ways to needle its foes.

If they did wish to disrupt shipping, they could briefly close off areas of the Gulf through declaring “military exercise areas,” “accidentally” release oil into the main channel or perhaps launch one-off and more deniable hit-and-run attacks.

The rhetoric, however, looks almost certain to continue.

“This isn’t the first time we have heard these types of threats,” said Alan Fraser, Middle East analyst for London-based risk consultancy AKE. “Closing of the Straits of Hormuz is the perfect issue to talk about because the stakes are potentially so high that nobody wants it to happen.”

Henry Smith, Middle East analyst at consultancy Control Risks, says he believes the only circumstances under which the Iranians would consider such action would be if the United States or Israel had already launched an overt military strike on nuclear facilities.

“Then, I think it would happen pretty much automatically,” he said. “The Iranians have been saying for a long time that is an option, and they would have little choice but to stick to that. But otherwise, I think it’s very unlikely.”

For many long-term watchers of the region, the real risk remains that in playing largely to domestic audiences, policymakers in Washington, Tel Aviv and Tehran inadvertently spark something much worse than they ever intended.

“Both sides are talking tough,” said Farhang Jahanpour, associate fellow at the Faculty of Oriental Studies at Oxford University. “Unfortunately it can very easily get out of hand and cause a conflagration. I blame hardliners on both sides. They are playing a very dangerous game of chicken.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.