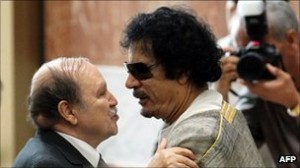

As the hunt for Muammar Gaddafi continues, Algeria has given the fugitive Libyan leader’s wife and three of his children refuge.

As the hunt for Muammar Gaddafi continues, Algeria has given the fugitive Libyan leader’s wife and three of his children refuge.

The move exposes it to accusations of siding with the fallen autocrat – and to the anger of Libya’s leaders in waiting.

It appears to be linked to the Algerian leadership’s poor relations with the Libyan National Transitional Council (NTC), which in turn betrays its deep-seated fear of instability spreading westwards.

On the face of it, Algerian officials said the decision to let in Safia, Aisha, Muhammad and Hannibal Gaddafi was made on “humanitarian grounds”, one of the exemptions included in a UN travel ban imposed on Col Gaddafi’s entourage in February.

Algeria’s ambassador to the UN, Mourad Benmehidi, told the BBC that his country was abiding by the “holy rule of hospitality” observed in the Sahara desert, through which the border between Libya and Algeria runs.

On Tuesday, Algerian officials said Col Gaddafi’s daughter Aisha had given birth to a baby girl hours after crossing over from Libya.

Its relations with the Gaddafi regime were close but bumpy. The Libyan leader’s forays into the politics of the Sahel troubled Algerian officials, who saw the area as their own zone of influence, and there were territorial disputes.

But relations with the National Transitional Council (NTC) have been notably worse, as Algeria has held out from granting the council recognition – the only country on the North African coast to do so.

Libyan rebels have even made claims, denied by the Algerian government, that Algeria sent mercenaries to help Col Gaddafi. A spokesman for Libya’s NTC called Algeria’s acceptance of Col Gaddafi’s close relatives an “act of aggression against the Libyan people”, and said the NTC would seek the Gaddafis’ extradition.

‘Fear of change’

One explanation for Algeria’s stance on Libya is its overt dislike for foreign intervention, particularly the kind of Western intervention that has helped bring the NTC to the brink of power.

This is rooted in Algeria’s painful experience of French rule, its faded image as a leader of post-colonial states, and a suspicion of Western motives in the Arab world.

It therefore opposed Nato’s mission in Libya, before unsuccessfully trying to encourage mediation through the African Union.

“Algerian diplomacy has failed, they have handled this badly and have always been late,” said Zoubir Arous, a professor at the University of Algiers.

Algeria reacted slowly and inadequately because President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who has led the country since 1999 but first became a minister as early as 1962, “wants to control everything” in the foreign policy sphere, he said.

A more practical worry is any knock-on effect on Algeria’s own stability.

“The regime has fear of profound and uncontrolled change in Libya” said Mr Arous. “It sees this as a risk for the whole region.”

This fear centres on a belief, repeatedly promoted by Col Gaddafi himself, that the NTC is vulnerable to extremist, Islamist influences, he said.

“Gaddafi created problems for Algeria for 42 years – they are not for him. But they have reservations about the composition of the council.”

“Everyone has arms, and there have been massacres on both sides,” Mr Arous said, adding that a fair trial for members of the Gaddafi regime seemed unlikely for now. “The situation is not under control.”

‘Miscalculating monstrously’

For months, there have been accounts in the Algerian media about the reported spread of weapons from Libya benefiting al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, which is based in Algeria.

Algeria has been boosting security along its border with Libya, and as news of the Gaddafi family arrival broke, Algerian newspaper El Watan also reported that the government had closed the frontier.

Algeria still faces a threat from the tail end of an insurgency launched after the army cancelled elections in 1992, just as an Islamist party was poised to win them.

But the Algerian government also draws much legitimacy from its achievement in largely overcoming this challenge.

Critics say it has long used the spectre of extremism to deflect attention from its own shortcomings, and has fallen back on this tactic to protect a security state of the kind that has suddenly come under pressure during the Arab Spring.

Algeria saw its own protests at the beginning of the year, which it contained with the help of heavy policing, hand-outs and divisions within the opposition.

The end of Col Gaddafi’s rule leaves Algeria and Morocco as the only states along the southern shore of the Mediterranean where the leadership remains intact.

“They know that they are on the list of the Arab Spring, they know that this is the movement of history,” said Mohamed Larbi Zitout, a former Algerian diplomat in Libya and member of the opposition movement Rachad.

“They can’t stop it, but they try to stop it because at the end of the day it’s a matter of life or death for them.”

Fawaz Gerges, a professor of Middle Eastern politics at the London School of Economics, said that could be a risky strategy and prove unpopular with the Algerian people.

“I would argue the Algerian regime is miscalculating monstrously,” he said. “Algeria itself is not immune to the revolutionary momentum sweeping the Arab world in the last six or seven months.”

BBC

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.