A 30-minute walk from Tahrir Square, in a dark, dilapidated room lighted by a single, bare bulb, members of the April 6 movement are meeting to decide the group’s future.

A 30-minute walk from Tahrir Square, in a dark, dilapidated room lighted by a single, bare bulb, members of the April 6 movement are meeting to decide the group’s future.

What began as a subdued discussion has become a bitter debate.

“Who are we?” one member demands. “A resistance group? Civil rights organization? Lobbying and pressure group?”

“Should we even exist anymore?” another asks. “We accomplished our mission. Mubarak is gone.”

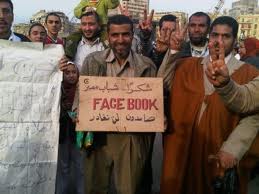

The group’s identity crisis has been spurred in recent weeks by rapid growth — from a fledgling Facebook page created to support workers who were planning a strike on April 6, 2008, into an organization that played a central role in Egypt’s revolution. It now claims more than 20,000 members and roughly 200,000 followers on Facebook.

Most are educated professionals in their 20s and 30s. They have experience in opposing government but little in reforming and working with it. And the divisions emerging in the group and others have been deepened by the fractured, everyone-gets-a-voice nature of the Internet, which once united the protest movement.

When one member suggests that the group become a political party, the meeting turns into a full-fledged shouting match. Politics — with its accompanying machinations of power, self-interest and corruption — are what pushed Egypt into a three-decade authoritarian regime, one member says. Why not focus on activism instead of wasting time on a political party?

It was, in many ways, so much easier during the revolution.

For those heady 18 days, Egypt’s young activists shared one vision and focused all of their efforts — tweets, Facebook posts, videos and blogs, as well as fists and stones — toward that goal: taking down Hosni Mubarak, the autocrat who had ruled Egypt for 30 years.

But now, with that goal accomplished, other targets have sprung up. There are, as some activists put it, as many goals and visions as there are Twitter accounts.

Some want to start building the infrastructure for Egypt’s new democracy. Others think that, as long as vestiges such as Mubarak’s decades-long emergency law remain in place and political prisoners remain in jail, the revolution cannot end. Then there are those who worry about the stalled economy and say the time for strikes has passed.

Even the physical space they once shared, Tahrir Square, has become a place of division as demonstrators have clashed violently with other Egyptians over whether protests should continue.

At the heart of the swirling chaos is a big question: Who speaks for this new Egypt and for the millions of protesters who made it possible? It is a call every group is rushing to answer in a bid to claim legitimacy, influence and, ultimately, the power to shape what kind of country will emerge from this time of transition.

Lack of structure

The meeting at the group’s headquarters — a gutted house donated by a sympathetic businessman — ends up running late into the night. A few April 6 members linger afterward and explain that such intense debates have become common among many youth movements.

There are disagreements over whether to negotiate with the military council running Egypt’s transitional government or to boycott it. There are divisions over whether to hold protests every day or only on Fridays, when more people participate.

Part of the problem, for groups such as April 6, is organizational structure, or lack thereof. Youths in Egypt proudly point out that theirs was a leaderless revolution, a deliberate philosophy born in part out of the nonviolence books and Serbian Otpor! movement that inspired the April 6 founders.

The problem also has to do with the movement’s origins online, where everyone has a right to post a comment. In the days after the revolution, the group tried applying similar principles to meetings, giving everyone who attended two minutes to speak. The resulting marathon sessions went on for hours with little consensus.

But the leaderless philosophy extends far beyond the April 6 group. During the revolution, several youth groups banded together to form the Coalition of the Youth of the Revolution, a loose-knit board that included two representatives from each faction. Since then, the coalition — which has played a large role in negotiating with the Egyptian military — has studiously avoided anointing any leaders.

In fact, before Mubarak stepped down, when one of the coalition’s members, Google executive Wael Ghonim, was released from captivity, some youth activists said they had asked Ghonim to scale back his media appearances. They noticed that media coverage had begun to identify him as the face of the revolution. Since then, he has largely faded from the spotlight, granting few interviews and restricting his public comments in recent weeks to Twitter and Facebook.

“Our reasoning is this,” said Muhammad Adal, 23, a core member of April 6. “A leader can be arrested, slandered, dragged down into the mud. But if your leader is an idea, this is something no one can kill.”

Movement without end

Although the revolution has ended, the impulse to revolt has only increased since Mubarak stepped down Feb. 11.

Each day, there are dozens of protests — by women for equal rights, by Coptic Christians against discrimination, by high school students against exams, by drivers angry about the price of gas. Even ballet dancers and musicians at Cairo’s opera house have held sit-ins over pay.

But perhaps the most surprising attempt at reform has come from within the Muslim Brotherhood, which has emerged as one of the most powerful political forces in post-Mubarak Egypt.

After being banned for years by the old regime, the Brotherhood is trying to become a legal political faction without panicking some Egyptians who worry that the group’s ultimate goal is to install an Islamic government.

Youths in the Brotherhood, however, have threatened to mobilize their own mass protests unless the group overhauls its leadership. They have asked for more transparency, a greater role for women and a modern media strategy.

In the earliest days of the revolution, Muslim Brotherhood youths rushed to protest, even as their elder leaders hesitated. In forming their movement, young members of the Brotherhood say they are drawing upon lessons from those days.

“Each night during the revolution in Tahrir Square, after the skirmishes, we talked with other youths and among ourselves,” said Kamal Samir Fargallah, 38, a business consultant, whose first act after the revolution was to create a Facebook group, as he had seen other groups do, calling for reform in the Brotherhood. “It was the first time we youths from different movements sat together. We learned from each other,” he said.

But even as they push to build a more modern, moderate Brotherhood, the group’s younger members know they risk alienating its leadership, which is still firmly in charge.

“It’s delicate,” said Mohammad al-Kassas, a youth leader in the Brotherhood. “For that reason, you see the overt attempt online, but underneath that are quiet efforts as well behind the scenes.”

Sitting at a downtown coffee shop in a slate-gray suit with a smartphone in each coat pocket, Samir spoke cautiously, playing down the divisions and being careful to avoid criticizing the old guard.

“We have the same goals. It is simply a difference in speed,” he said. “The old leaders are driving at 80 kilometers an hour because this used to be outlawed. We are pointing to the new speed limit, asking why not go 120?”

But half an hour into the conversation, in a moment of candor, he said: “In the future, the young people will be the leaders of Egypt, even in the Muslim Brotherhood. This is what the revolution showed all of us. The young are the only ones with the flexibility to adapt.”

Struggling to be heard

But not everyone has so easily found a voice in the new Egypt.

Among the several hundred young and old protesters sporadically converging at Tahrir Square, many have grown angry and disillusioned with the youth movements, which have mostly abandoned Tahrir, returning only on Fridays, the biggest day of protests.

As they point out, key demands from the revolution remain unmet: the release of political prisoners, elimination of the emergency law, a civilian-led transitional government.

“Why is it that only these youth leaders get to negotiate with the government? Did we not fight the revolution so that we would all have a voice?” Osama Ibrahim, 36, an elementary school music teacher, asked on a recent day in Tahrir Square.

Ibrahim hitchhiked to Cairo from his home two hours north in Kafr el-Sheikh on Feb. 2, after he saw pro-Mubarak forces attacking protesters on the news. He stayed in Tahrir for weeks, braving tear gas, fighting off thugs, sleeping on the ground, sharing a blanket with other protesters.

But these days, the joy he felt when Mubarak finally stepped down has turned to bitterness. He is protesting as hard as ever, but no one, he says, is listening.

The biggest danger to the country now, he says, is the fact that the military was put in charge of the transition. And the only way to solve it, he said, is with a transitional presidential council that includes civilians — an idea that was popular during the revolution but has since largely been abandoned.

He tried calling, texting and sending Facebook messages to the now-prominent figures of the youth coalition to make his point. He tried handing out fliers and mobilizing fellow demonstrators.

Then, with two like-minded men, he began plotting a new course, a plan lifted straight out of the youth activists’ playbook. Convening on a recent Friday at an Internet cafe, Ibrahim and his collaborators logged on to Facebook and created a page to launch a new movement.

The only question remaining was what to call themselves. It had been just weeks since Mubarak stepped down, since Ibrahim and others in the square had won back their country, but already he could feel it slipping away.

After much debate, they finally settled on a name: the Movement to Save the Revolution.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.