Demonstrators marched peacefully through the Yemeni capital Sana’a on Thursday, quashing fears that the volatile situation in the south Arabian state would explode if the protests escalated into violence. Anti-government protesters had promised a Day of Rage, aimed at forcing President Ali Abdullah Saleh to step down, but by midday the protesters had already drifted home. Unlike in Tunisia and Egypt, Yemeni street protests have so far only managed to teeter on the edge of an uprising.

Over 20,000 people marched in front of Sana’a University on Thursday, holding signs declaring: “Enough Saleh, Get Out!” But a couple of miles away, in the heart of the historic Old City, Saleh supporters were holding a smaller counter-demonstration. Saluting the President and accusing the opposition of disloyalty, thousands of pro-government protesters marched through the cobblestone streets to Tahrir Square (which shares its name with the plaza in Cairo) where the ruling party had erected tents for them.

Protestor Um al Thafri told TIME that she had prayed the President would be saved from “conspiracies.” “God damn everyone who goes against [Saleh],” she shrieked. “The future will not bring better than him.” Observers claim that the pro-Saleh protesters are tribal loyalists, shipped in on buses by the government. There were also allegations that anti-Saleh demonstrators traveling to the capital for Thursday’s march had been refused entry. True or not, there is no doubt that after two weeks of protests, the movement to oust Saleh lost steam today. “These marches are useless, as they have become mere rituals,” Mohammed al Dhahri, a political science professor at Sana’a University, tells TIME.

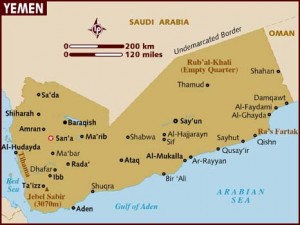

Covered in vast sandy deserts, lush green mountains and sultry coastal plains, Yemen is not like its neighbors in North Africa. Most of the Yemeni people live off the land in rural areas, disconnected from neighboring communities by harsh terrain — here, you can’t mobilize the masses through Twitter.

“Grassroots opposition to Saleh’s regime has, up to this point, been fragmented, largely taking place at the physical margins of the country,” says Kate Nevens, a Yemen expert at the U.K.-based think-tank Chatham House. She adds that, in Egypt the movement is essentially an urban one, whereas the discontent in Yemen is “widespread and in [the] provinces.”

With an extremely low literacy rate and a middle class a fraction of the size of those in Tunisia and Egypt, disgruntled Yemenis have only been able to pull together frustratingly low-key protests. After the government arrested some of the opposition leaders in late January, the movement seemed to gain momentum — but quickly died down after all were released the following day.

Like other Arab leaders, Saleh has the benefit of a week’s hindsight as protests progress in Egypt. The Yemeni government is no doubt scrupulously analyzing where Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak went wrong in his attempts to inspire calm over the past few days. Hoping to avoid Thursday’s demonstration, Saleh offered salary rises for civil servants and said on Wednesday that he would step down at the end of his term in 2013 and not hand over power to his son. Although his concessions were rebuffed as lies — he has made similar promises, and broken them, in the past — the opposition, lacking a clear figurehead like Egypt’s Mohammed ElBaradei, still has not been able to pull together the mass demonstrations they need.

Thursday’s lackluster protest almost certainly has Washington breathing a tentative sigh of relief. Saleh has become a close ally in the war on terror. Using a carrot-and-stick approach — mostly carrot, with up to $250 million in military aid allocated for this year — the U.S. has been trying to battle al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, Yemen’s local branch, through Saleh’s government. The fear is that if Saleh loses power, it will be almost impossible to fight the terrorist group responsible for trying to bomb a Detroit-bound passenger jet on Christmas Day 2009 and sending explosive packages to Chicago late last year.

“Nobody wants Saleh to go — not the U.S., Europe, Saudi Arabia or the Gulf countries,” says Christopher Boucek, a Middle East associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a Washington-based think tank. “The U.S. is starting to realize that al-Qaeda operating in Yemen presents the biggest threat to U.S. national security.”

Washington has been forging a strong relationship with Saleh for some time. On Thursday, WikiLeaks published a 2005 diplomatic cable from the U.S. Embassy in Sana’a titled: “Priorities for Washington Visit: Saleh Needs to be Part of the Solution.” The President has managed to keep the country stable for three decades, but only just. Any power vacuum could be disastrous in this tribal society, already fighting two civil wars and where every family home has a Kalashnikov. Saleh has managed to stay in power only through a complex system of personal relationships, patronage networks and tribal balancing acts — without a state structure, the system isn’t built for someone else to step in and take the reins.

And although the streets of Sana’a were calm on Thursday, the situation could still get messy, especially if Egypt’s Mubarak leaves and the people of Yemen get a second wind. “There may not be a middle class in Yemen, but there is a large, corrupt elite and everyone else,” says Boucek. “The potential for things to go wrong is very high. It could get violent.”

Time

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.