By: Dalila Mahdawi

The people who went missing during Lebanon’s civil war in the 1970s and 80s are in danger of being forgotten as their parents and siblings grow older. One mother I knew died without ever discovering what happened to her children.

Spring is one of the most beautiful times of the year. The trees are in blossom, the Sun shines and the weather is mild. But for many Lebanese, this season is tainted.

Audette Salem was just one woman whose loved ones disappeared in Lebanon’s civil war.

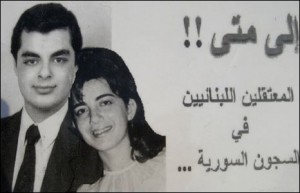

Some 17,000 people vanished during the bloody conflict, most – it is thought – abducted and killed by militias. But some believe a few hundred may still be alive in Syrian jails.

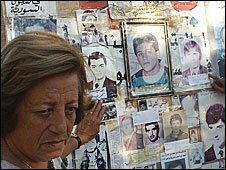

I first met Audette in a tent outside the United Nations headquarters in Beirut.

She, along with other families of the missing, had set up home there to demand an investigation into their disappearance.

A 77-year-old woman with a small frame and a resigned look on her face, Audette quietly told me about the day her son and daughter disappeared.

‘Stop looking’

It was 1985, and 19-year-old Marie-Christine and 22-year-old Richard were driving home for lunch with their elderly uncle George.

Somewhere along the way they were kidnapped.

At home, Audette waited for them to arrive – for hours – anxiously looking out of the window for signs of their orange Volkswagen.

When it dawned on her what might have happened, she went to the militia leaders, risking her own life to glean what information she could.

Invariably, Audette told me, the men would tell her they didn’t know anything.

She never saw or heard from her family again.

Five years later, when the war ended, Audette again visited the militia leaders, who had, by then, become government officials.

She said they cold-heartedly told her to stop looking and move on.

With the passing of time, the chances that Richard, Marie-Christine and George were still alive diminished.

Yet Audette refused to give up hope – it was all she had left.

She would tidy her children’s bedrooms as though they might reappear that very evening.

She rearranged Richard’s guitars, cigarettes and razors, and dusted Marie-Christine’s bed and make-up.

War amnesia

Audette was interviewed three times by a commission established by the government to look into the disappearances.

But she felt the commission let her down – it never published its findings and did little, she claimed, to investigate the hundreds of mass graves dotted around the country.

Shortly after the war ended, the Lebanese government passed an amnesty law protecting militia members from being prosecuted for war crimes. It also effectively snuffed out any hopes of a real debate about the bloodshed.

Indeed, it seems the war amnesia is no accident. Since I first came to Lebanon 10 years ago, I’ve seen traces of the conflict almost completely wiped away.

Back then, I was stunned by all the bullet-riddled buildings. Now, I’m shocked by how few of those buildings are left to remind people of the war.

It is almost as if it never happened.

There are no official war memorials or commemoration dates, and up until a few years ago, the site of an infamous massacre in the Sabra and Shatila Palestinian refugee camps was a rubbish dump.

Because of the reluctance to stir up memories of the war, little has been done by the government to investigate the whereabouts of the missing.

Prime Minister Saad Hariri has said he will bring up the issue of the disappeared in talks with the Syrians, whose military were present in Lebanon soon after the start of the civil war and until just five years ago.

But many are sceptical anything significant will come out of it.

“Why,” people ask, “should the Lebanese expect the Syrians to tell them where their missing are, if the Lebanese themselves seem unable to answer that question?”

Too late

As some of my Lebanese friends tell me, the war may be over on paper, but in people’s minds it rages silently on.

Sectarian tensions, mostly between rival Christian and Muslim groups, are still very much a part of Lebanon’s social fabric.

Without a proper discussion of why the war happened and what occurred during the conflict, many believe Lebanon’s troubles will never truly go away.

For people like Audette, any truth which is uncovered about the war will have come too late.

She lived in her protest tent for 1,495 days, giving up the comforts of a real home to brave hot summers and blustery winters in the company of others who had lost relatives.

But last May she was killed by a speeding car as she crossed the road near her tent.

At her funeral, held at the tent, more than 100 friends gathered to pay their last respects.

They also came to deliver a message to the government: Audette spent the last 25 years searching for news of her children and died no closer to finding it.

This spring, those friends are no doubt hoping Audette’s prayers will one day be answered.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.