By Abbas Djavadi

Imagine the following: The de facto independent Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq declares independence, secedes from Iraq, and inspires Kurds in Turkey and Iran to join a “Greater Kurdistan.” Shi’ite Arab parties in Iraq follow suit and found a small, Iran-friendly country mired in tensions with Iraq’s Sunnis and other Arab countries. Fighting erupts not only over the disputed oil-rich Kirkuk in the north, but also among Shi’a and Sunnis, and among Arabs and Kurds, and Turkomans in all mixed cities and towns across what used to be Iraq. If the violence and chaos ever cleared up, Iraq would be split into two or more states, provoking tensions that threaten the security of the entire Middle East.

Despite the emergence of a pro-Iranian ministate, this is probably the worst-case scenario in the minds of Tehran’s foreign-policy makers.

Of course, this drastic scenario appears far from likely as Iraq votes for a new parliament on March 7. But unless Iraq develops mechanisms for managing ethnic and sectarian tensions, it cannot be excluded that Shi’ite Arabs, Sunni Arabs, and Kurds could begin to move in different directions.

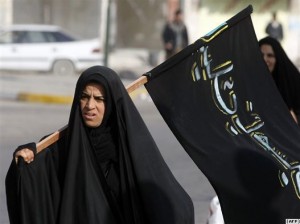

Two possible developments in particular could provoke such a trend. Consolidating their power in parliament and the government, major Iran-friendly Shi’ite groups could further try to alienate and exclude Sunni groups, and Sunni Arabs could respond with increased insurgency and violence. Or, emboldened by their kingmaker role and favorable election results, the Kurdistan Alliance — consisting of the two main Kurdish political parties — could become more aggressive in its bid to incorporate Kirkuk into the Kurdish region.

It is no coincidence that so many comments by Iranian President Mahmud Ahmadinejad lately underscore support for a “united and internally secure” Iraq. For some, however, Iranian statements are too good to be honest. Recently, General Ray Odierno, the commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, accused the Iranian government of buying votes and pumping money and other assistance to its allies in Iraq. Further, Iran supported the ban on some 500, mostly Sunni, would-be candidates participating in the elections. Although that move was presented as “de-Ba’athification,” many saw it as a bid to strengthen the position of Shi’ia and, ultimately, of Iran.

‘Brotherly Relations’

Behind the populist rhetoric about “brotherly relations between Iran and Iraq,” however, Iran’s role in Iraqi affairs seem to be directed more toward gaining influence in order to reduce security threats against Iran rather than to destabilize Iraq. A recent study by the International Crisis Group found that “the evidence of attempted destabilizing Iranian intervention is far less extensive and clear than is alleged.”

“The only solution to the dilemma in Iraq is to withdraw U.S. forces and leave all state affairs to the Iraqi government” — that used to be the bottom line repeatedly stressed by Ahmadinejad and other Iranian officials. And it still is, even though it has been less vigorously stated since Washington announced plans to pull out all its troops by the end of 2011. The United States has already withdrawn its troops from major Iraqi cities and is expected to speed up that process after the elections.

The toppling of the Islamic republic’s two arch-enemies — the Taliban of Afghanistan in 2001 and Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003 — was an unintentional historic gift from Washington to Tehran. But since then, Iran has felt sandwiched between U.S. troops based in Afghanistan and Iraq. With the “fists still unclenched” in U.S.-Iranian relations, reducing U.S. pressure in the two neighboring countries remains one of Iran’s highest priorities.

Dilemma For Tehran

By 2012, Iraqi security forces should complete the takeover from U.S. troops. But what happens if the country’s internal security deteriorates as a result? Iranian media have indicated that Tehran officials, while not speaking publicly, privately are increasingly nervous about U.S. troops leaving before the Iraqi government gains full control of the situation. Last week, Iraqi Defense Minister Abdel Qader Jassim warned that the U.S. pullout would pose challenges to Iraq’s security. “Iraq’s armed forces will not finish their modernization program until 2020,” Jassim noted.

For Iran, this poses a dilemma. Tehran wants the United States to leave but is troubled by the possible consequences of a premature troop withdrawal.

Iranian leaders embrace the role of a “big brother” when talking about Iraq. Last week, Ahmadinejad said that since the overthrow of Hussein, Iraq has become “a strong bastion in defense of the Islamic revolution.”

However, despite all the blood and destruction since 2003, Iraq has slowly but surely developed a far more representative and democratic governance than “big brother” Iran. Iraq has no “supreme leadership” system based on an unelected cleric with final authority on all major issues. It has not banned opposition political parties or media. And Iraq’s ethnic groups enjoy an incomparably broader range of rights, including autonomy. For the current parliamentary campaign, Iraq’s competing Shi’ite groups have created alliances including Sunnis and Christians.

Which Way?

As for religion, Iraq’s highest Shi’ite cleric, Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, does not interfere directly in active politics as a rule. Recently, al-Sistani issued a statement saying that he is not supporting any political group or personality in the March 7 elections. Before Iran’s presidential election in June 2009, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei publicly endorsed the hard-line candidate, Ahmadinejad.

“We will accept any decision made by the Iraqi people,” Ahmadinejad said recently. But success in Iraq’s admittedly complicated democratic procedure would establish a model for the Middle East and for Iranians — a model of a Shi’a-majority government that is broadly secular and moderate. This must concern the hard-liners in Tehran who expect Iraq to become “a bastion of the Islamic revolution,” an Arab copy of Tehran’s regime.

There are no signs of any immediate political earthquake after this weekend’s parliamentary elections in Iraq. But it remains to be seen whether seven years after the overthrow of the Hussein regime, the voting will produce a gradual and increasingly peaceful continuation of the course that started with the first parliamentary elections in 2005 — or pave the way for the country to reverse its course and undo the progress that has been achieved. RFER

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.