If Edward Snowden taught the world anything, it’s that governments now have the ability to pry into the personal and political affairs of their own citizens at relative ease, and Lebanon is no exception.

In the wake of the bombshell revelations illustrating the country’s state-sponsored spying activities – directed at its own people – Lebanon has now been thrust at the forefront of this discussion, joining a long list of nations that partake in such pervasive behavior.

The crux of the report, compiled by cybersecurity firm Lookout Inc. and digital rights NGO the Electronic Frontier Foundation, suggests that Lebanon’s government is, at the very least, complicit in this blatant cyber espionage campaign; undertaken by a group of operatives under the banner of Dark Caracal.

Following Annahar’s thorough analysis of the report, below are the key findings and results that show the severity of the breach and what it encompasses.

According to the report, Dark Caracal operators were stationed inside the government-owned General Directorate of General Security (GDGS) building after researchers from Lookout and EFF acquired information from test Android devices on which the hackers trialed their attacks, before using a WiFi geo-tracking service to pinpoint their exact location.

The IP addresses on the attackers’ servers originated from the state-owned telecom operator Ogero, with two of these addresses located just south of the bulky GDGS building which is possibly a switching or central hub for the telecom company.

The GDGS building is home to one of the country’s intelligence agencies and is situated at the intersection of Beirut’s Pierre Gemayel and Damascus Streets in Beirut.

Lookout and EFF’s researchers traced the first attacks to January 2012, when Dark Caracal initiated an early mobile surveillance campaign, with the investigation running until January 2018 after the spying campaign was exposed.

Researchers discovered four different aliases associated with Dark Caracal, along with two domains, and two phone numbers, with the email address op13@gmail.com at the center of it all.

Further analysis of the data generated revealed ‘Nancy Razzouk’, ‘Hassan Ward’, ‘Hadi Mazeh’, and ‘Rami Jabbour’ as the chosen aliases by the associated personas, with the contact details for ‘Nancy’ matching the public listing for a Beirut-based individual by that name.

PLATFORMS BREACHED AND METHODS

According to the report by Lookout Inc. and EFF, Dark Caracal was able to cast its net wide by gaining deep insight into each of the victim’s lives. It acquired these insights through a series of multi-platform surveillance campaigns that kicked off with desktop attacks, while later pivoting to mobile devices.

“During our research, we found almost 90 indicators of compromise used in the breaching campaigns being, 11 Android Malware IOCs, 26 desktop malware IOCs, 60 domains, IP Addresses and WHOIS information,” the report said.

The platforms used for likely security breaches are WhatsApp, Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, Primo, Threema, Orbot TOR Proxy, Psiphon, Plus Messenger, and Signal.

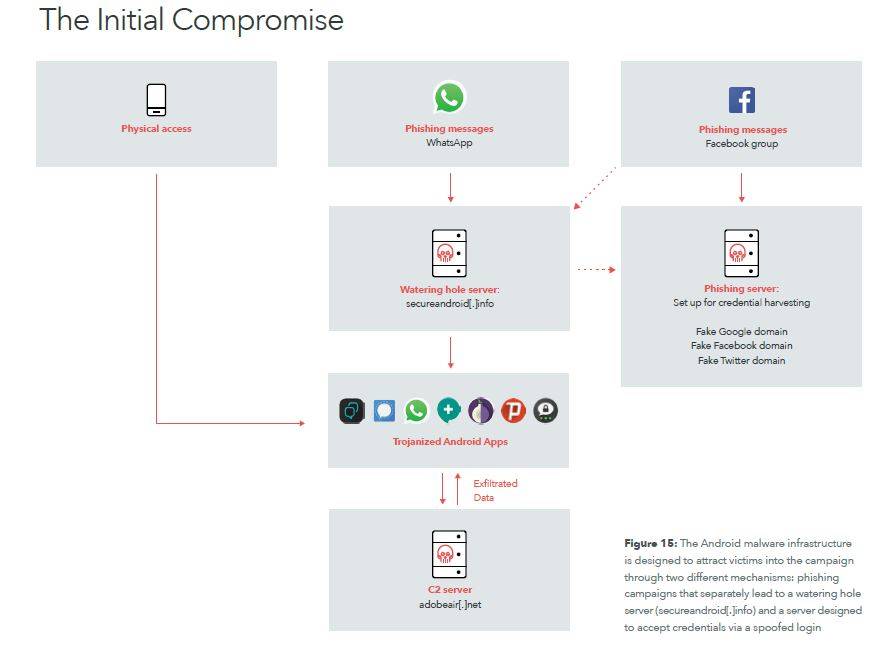

Dark Caracal relied primarily on social engineering via posts on Facebook groups and WhatsApp messages to compromise target systems, devices, and accounts. At a high-level, the attackers designed three different kinds of phishing messages, the goal of which is to eventually drive victims to a watering hole controlled by Dark Caracal.

The group’s infrastructure hosted phishing sites, which look like login portals for well-known services, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google. The investigation found links to these pages in numerous Facebook groups that included “Nanys” in their titles.

A phishing scam is the attempt to obtain sensitive information such as usernames, passwords, and credit card details, often for malicious reasons, by disguising as a trustworthy entity in an electronic communication.

While a watering hole is a security exploit in which the attacker seeks to compromise a specific group of end users by infecting websites that members of the group are known to visit. The goal is to infect a targeted user’s computer and gain access to the network at the target’s place of employment.

“The Android malware family mainly trojanizes messaging and security applications and, once it compromises a device, it is capable of collecting a range of sensitive user information,” the report explained.

Dark Caracal distributed trojanized Android applications with its custom-developed mobile surveillanceware through its watering hole, secureandroid[.]info. Many of these downloads included fake messaging and privacy-oriented apps.

Dark Caracal used phishing messages through popular applications, such as WhatsApp, in order to direct people to the watering hole.

Phishing links posted in Dark Caracal linked Facebook groups include politically themed news stories, links to fake versions of popular services, such as Gmail, and links to trojanized versions of WhatsApp.

Four Facebook profiles similar in theme “liked” the phishing groups. Dark Caracal likely used these fake profiles to initiate communication with victims and build a rapport before directing them either to content on the “Nanys” Facebook groups or to the secureandroid[.]info domain directly.

TYPE OF STOLEN DATA

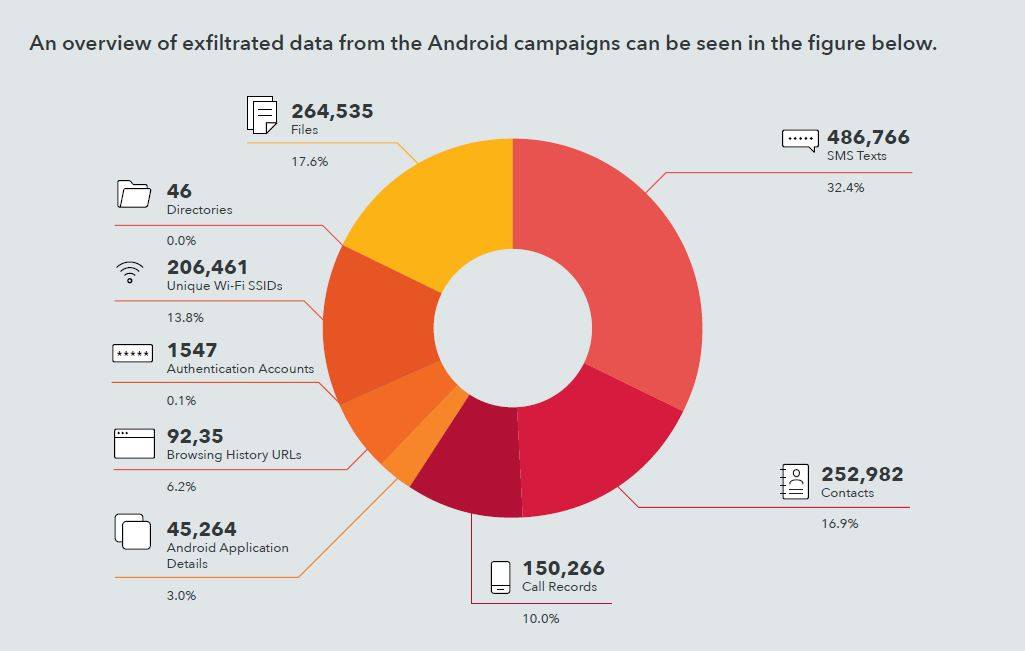

According to the report, the type of exfiltrated data includes SMS messages, call records, contacts, images, account information, bookmarks and browsing history, installed applications, audio recordings, WiFi details, WhatsApp, Telegram, and Skype databases, legal and corporate documentation, and finally, file and directory listings.

Exfiltrated data can be divided into the following categories of information:

– SMS messages: Messages included personal texts, two-factor authentication and one-time password pins, receipts and airline reservations, and company communications.

– Contact Lists: This data included numbers, names, addresses, bank passcodes, PIN numbers, how many times each contact was dialed, and the last time the contact was called.

– Call logs: This data included a full record of incoming, outgoing, and missed calls along with the date and duration of the conversation.

– Installed Applications: This data included app names and version numbers.

– Bookmarks and Browsing History: This data included bookmarks and browsing history from web pages. This data was seen in only one Android campaign called oldb, but it clearly identified victims that were active in political discourse.

– Connected Wi-Fi Details: This data included observed Wi-Fi access point names, BSSIDs, and signal point strength.

– Authentication Accounts: This data included the login credentials and which applications are using it.

– File and Directory Listings: This data included a list of personal files, downloaded files, and temporary files, including those used by other applications.

– Audio Recordings and Audio Messages: This data included audio recordings of conversations, some of which identified individuals by name.

– Photos: This data included all personal and downloaded photographs, including profile pictures.

– Skype Logs Databases: The data included the entire Skype AppData folder for certain victims, including messaging databases.

“It is common to see smartphone photos backed up to this location, which most often contains personal photographs of family and friends taken by the individual being targeted,” The report added.

The investigation found the largest collection of data from a single command and control server that operated under the domain adobeair[.]net.

Over a short period of observation, devices from at least six distinct Android campaigns communicated with this domain resulting in 48GB of information being exfiltrated from compromised devices.

Windows campaigns contributed a further 33GB of stolen data.

The remainder of the data contained desktop malware samples, spreadsheet reports on victims, and other files.

TARGETS AND THEIR DEMOGRAPHICS

Dark Caracal targeted a broad range of victims spanning members of the military, government officials, medical practitioners, education professionals and academics, civilians from numerous fields, financial institutions, manufacturing companies, and defense contractors.

“We have identified hundreds of gigabytes of data exfiltrated from thousands of victims, spanning 21+ countries in North America, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia,” the report highlighted.

Victims were found to speak a variety of languages and were also from a wide range of countries. “We discovered messages and photos in Arabic, English, Hindi, Turkish, Thai, Portuguese, and Spanish in the examined data,” the report said.

The countries are the following:

HOW DARK CARACAL WAS EXPOSED

Even the most primitive hacking tools and methods can be effective when those targeted lack the required aptitude to protect themselves, leading to a substantial data breach without the need for a sophisticated spying apparatus.

Yet, this lack of elevated prowess on behalf of Dark Caracal as well led to their eventual downfall, after the hackers carelessly left behind hundreds of gigabytes of intercepted and stolen data on the open internet.

“It’s almost like thieves robbed the bank and forgot to lock the door where they stashed the money,” Mike Murray, Lookout’s head of intelligence, told the Associated Press.

This is only the second instance when such carelessness was on display, with the only other example of such ineptitude emanating from Kazakhstan in 2016, when Lookout similarly uncovered a series of attacks targeting journalists and political activists critical of that authoritarian government, along with their family members, lawyers, and associates.

Ironically, that particular data haul led researchers at Lookout to Dark Caracal after researchers linked elements from the Kazakh breach to Lebanon by stumbling across an open server riddled with images, photos, private conversations, text messages and much more.

BLATANT BREACH OF PRIVACY RIGHTS

It’s always hard to give the government the benefit of the doubt in regards to domestic surveillance, yet skepticism mounts further when looking at Lebanon’s law pertaining to wire-tapping, the collection of data, and illegally obtaining sensitive information.

This indiscriminate spying on citizens’ communications on behalf of the GDGS is in violation of Lebanese law, according to a lawyer who spoke to Annahar on condition of anonymity.

The warrantless spying on individuals convicted of no crime, for no probable cause, is in direct contravention of the core protections guaranteed by law #140, ratified on October 27, 1999, the lawyer said.

Article 1 of law #140 clearly prohibits the collection of information or monitoring of communication of any kind, unless in specific cases.

With the government expected to hedge itself on the basis of keeping the country safe, article #9 of the same law stipulates that authorities wishing to surveil any form of communications must obtain the approval of the Defense Minister, Interior Minister, as well as the Prime Minister; credibly showing that the surveillance is related to terrorist activities, protecting national security, or fighting organized crime.

The request must also specify the means of communication authorities wish to intercept, the information being sought, as well as the duration of the operation which cannot exceed a two-month period unless extended in accordance with applicable law.

Another article of the law stipulates that Lebanon’s security agencies must go through the proper legal channels to obtain a warrant in order to surveil a citizen, by providing a judge with necessary evidence accompanying their case.

Abuses of powers, the overstepping of authority, and the circumventing of legal guidelines is punishable by up to three years in prison, accompanied by a fine of up to LBP100 million.

Source: An Nahar

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.