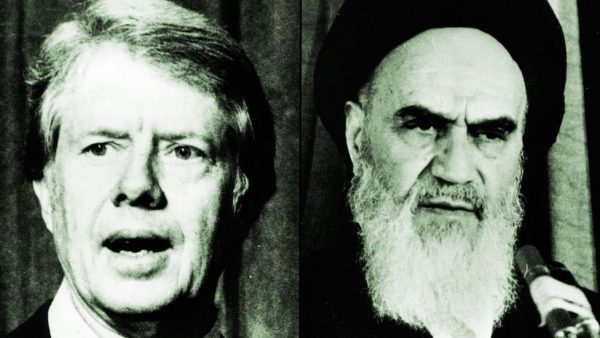

On 27 January, 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini – founder of Iran’s Islamic Republic, the man who called the United States “the Great Satan” – sent a secret message to Washington.

On 27 January, 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini – founder of Iran’s Islamic Republic, the man who called the United States “the Great Satan” – sent a secret message to Washington.

From his home in exile outside Paris, the defiant leader of the Iranian revolution effectively offered the Carter administration a deal: Iranian military leaders listen to you, he said, but the Iranian people follow my orders.

If President Jimmy Carter could use his influence on the military to clear the way for his takeover, Khomeini suggested, he would calm the nation. Stability could be restored, America’s interests and citizens in Iran would be protected.

At the time, the Iranian scene was chaotic. Protesters clashed with troops, shops were closed, public services suspended. Meanwhile, labour strikes had all but halted the flow of oil, jeopardising a vital Western interest.

Persuaded by Carter, Iran’s autocratic ruler, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, known as the Shah, had finally departed on a “vacation” abroad, leaving behind an unpopular prime minister and a military in disarray – a force of 400,000 men with heavy dependence on American arms and advice.

Khomeini feared the nervous military: its royalist top brass hated him. Even more worrying, they were having daily meetings with a US Air Force General by the name of Robert E Huyser, whom President Carter had sent on a mysterious mission to Tehran.

The ayatollah was determined to return to Iran after 15 years in exile and make the Shah’s “vacation” permanent. So he made a personal appeal.

In a first-person message, Khomeini told the White House not to panic at the prospect of losing a strategic ally of 37 years and assured them that he, too, would be a friend.

“You will see we are not in any particular animosity with the Americans,” said Khomeini, pledging his Islamic Republic will be “a humanitarian one, which will benefit the cause of peace and tranquillity for all mankind”.

Khomeini’s message is part of a trove of newly declassified US government documents – diplomatic cables, policy memos, meeting records – that tell the largely unknown story of America’s secret engagement with Khomeini, an enigmatic cleric who would soon inspire Islamic fundamentalism and anti-Americanism worldwide.

This story is a detailed account of how Khomeini brokered his return to Iran using a tone of deference and amenability towards the US that has never before been revealed.

The ayatollah’s message was, in fact, the culmination of two weeks of direct talks between his de facto chief of staff and a representative of the US government in France – a quiet process that helped pave the way for Khomeini’s safe return to Iran and rapid rise to power – and decades of high-stakes tension between Iran and America.

In the official Iranian narrative of the revolution, Khomeini bravely defied the United States and defeated “the Great Satan” in its desperate efforts to keep the Shah in power.

But the documents reveal that Khomeini was far more engaged with the US than either government has ever admitted. Far from defying America, the ayatollah courted the Carter administration, sending quiet signals that he wanted a dialogue and then portraying a potential Islamic Republic as amenable to US interests.

To this day, former Carter administration officials maintain that Washington – despite being sharply divided over the course of action – stood firm behind the Shah and his government.

But the documents show more nuanced US behaviour behind the scenes. Only two days after the Shah departed Tehran, the US told a Khomeini envoy that they were – in principle – open to the idea of changing the Iranian constitution, effectively abolishing the monarchy. And they gave the ayatollah a key piece of information – Iranian military leaders were flexible about their political future.

What transpired four decades ago between America and Khomeini is not just diplomatic history. The US desire to make deals with what it considers pragmatic elements within the Islamic Republic continues to this day. So does the staunchly anti-American legacy that Khomeini left for Iran.

Message to Kennedy

It wasn’t the first time Khomeini had reached out to Washington.

In 1963, the ayatollah was just emerging as a vocal critic of the Shah. In June, he gave a blistering speech, furious that the Shah, pressed hard by the Kennedy administration, had launched a “White Revolution” – a major land reform programme and granted women the vote.

Khomeini was arrested. Immediately, three days of violent protests broke out, which the military put down swiftly.

A recently declassified CIA document reveals that, in November 1963, Khomeini sent a rare message of support to the Kennedy administration while being held under house arrest in Tehran.

It was a few days after a military firing squad executed two alleged organisers of the protests and ahead of a landmark visit by the Soviet head of state to Iran, which played into US fears of Iran tilting towards a friendlier relationship with the USSR.

Khomeini wanted the Shah’s chief benefactor to understand that he had no quarrel with America.

“Khomeini explained he was not opposed to American interests in Iran,” according to a 1980 CIA analysis titled Islam in Iran, partially released to the public in 2008.

To the contrary, an American presence was necessary to counter the Soviet and British influence, Khomeini told the US.

It’s not clear if President Kennedy ever saw the message. Two weeks later, he would be assassinated in Texas.

A year later, Khomeini was expelled from Iran. He had launched a new attack on the Shah, this time over extending judicial immunity to US military personnel in Iran.

“The American president should know that he is the most hated person among our nation,” Khomeini declared, shortly before going into exile.

Fifteen years later, Khomeini would end up in Paris. He was now the leader of a movement on the verge of ridding Iran of its monarchy. So close to victory, the ayatollah still needed America.

Key players

Iran

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini – Shia Muslim religious leader, living in exile in Paris in early 1979

Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti – Khomeini’s second-in-command in Iran, a Shia cleric seen by the US as a pragmatist

Ebrahim Yazdi – Iranian-American physician living in Houston, Texas, who became a spokesman and advisor to Khomeini

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi – the last king of Iran, formerly backed by the US government

Shapour Bakhtiar – the Shah’s last prime minister

Carter administration

William Sullivan – the US ambassador to Iran

Cyrus Vance – US Secretary of State

Warren Zimmermann – a political counsellor with the US embassy in France, used as a messenger for the US to Khomeini

Robert E Huyser – an US Air Force general sent by Carter on a secretive mission to Tehran in January 1979

By January 1979, Khomeini had the momentum, but he also deeply feared a last-minute American intervention – a repetition of the 1953 coup, when the CIA had helped put the Shah back in power.

The situation became explosive after the Shah’s new prime minister, Shapour Bakhtiar, deployed troops and tanks to close the airport, disrupting Khomeini’s planned return in late January.

It seemed Iran was on the brink of a civil war: the elite Imperial Guard divisions were ready to fight to the death for their king; the die-hard followers of the Imam were ready for armed struggle and martyrdom.

The White House feared an Iranian civil war that would have major implications for US strategic interests. At stake were the lives of thousands of US military advisors; the security of sophisticated American weapons systems in Iran, such as F-14 jets; a vital flow of oil; and the future of the most important institution of power in Iran, the military.

It was less alarmed by the rise of Khomeini, and the downfall of the Shah.

But President Carter had previously rejected a proposal to cut a deal between Khomeini and the military.

On 9 November 1978, in a now-famous cable, “Thinking the Unthinkable,” the US ambassador to Iran, William Sullivan, warned that the Shah was doomed. He argued that Washington should get the Shah and his top generals out of Iran, and then make a deal between junior commanders and Khomeini.

Sullivan’s bold proposal caught President Carter off-guard, and caused their relationship to go sour.

But by early January, the reluctant president concluded that the Shah’s departure was necessary to calm the opposition.

Amid reports of an impending military coup, the president summoned his top advisors on 3 January. After a brief discussion, they decided to subtly encourage the Shah to leave, ostensibly for a vacation in California.

“A genuinely non-aligned Iran need not be viewed as a US setback,” the president said, according to minutes of the meeting.

That day, Carter dispatched General Robert E Huyser, Deputy Commander of US Forces in Europe, to Tehran to tell the Shah’s generals to sit tight and “not jump into a coup” against Prime Minister Bakhtiar.

But Bakhtiar had no real support among the opposition, who called him the Shah’s agent.

Sullivan praised Bakhtiar’s courage to his face, but behind his back, told Washington that the man was “quixotic”, playing for high stakes, and would not take “guidance” from the US.

The state department saw his government as “not viable”. The White House strongly backed him in public, but in private, explored ousting him in a coup.

“The best that can result, in my view, is a military coup against Bakhtiar and then a deal struck between the military and Khomeini that finally pushes the Shah out of power,” wrote Deputy National Security Advisor David Aaron to his boss Zbigniew Brzezinski on 9 January 1979.

“Conceivably this deal could be struck without the military acting against Bakhtiar first,” he added.

Two days later, President Carter finally told the depressed and cancer-stricken Shah to “leave promptly”.

By then, a broad consensus had emerged within the US national security bureaucracy that they could do business with the ayatollah and his inner circle after all.

Khomeini had sent his own signals to Washington.

“There should be no fear about oil. It is not true that we wouldn’t sell to the US,” Khomeini told an American visitor in France on 5 January, urging him to convey his message to Washington. The visitor did, sharing the notes of the conversation with the US embassy.

In a key meeting at the White House Situation Room on 11 January, the CIA predicted that Khomeini would sit back and let his moderate, Western-educated followers and his second-in-command, Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti, run the government.

Beheshti was considered by US officials to be a rare bird: a pragmatic, English-speaking cleric with a university education, experience of living in the West, and close ties to Khomeini. In short, he was someone with whom the Americans could reason.

“We would do a disservice to Khomeini to consider him simply as a symbol of segregated education and an opponent to women’s rights,” said the then-head of the State Department Intelligence Bureau, Philip Stoddard.

President Carter was relieved that General Huyser had now arrived in Tehran. Huyser was good at following orders, and had the confidence of the Iranian military leaders.

Once there, Huyser was tasked with taking the temperature of the military’s top brass and convincing them to “swallow their prestige” and go to a meeting with Beheshti. The US believed such a meeting would lead to a military “accommodation” with Khomeini.

To help break the stalemate, President Carter swallowed his own prestige. On the evening of 14 January, US Secretary of State Cyrus Vance sent a cable to US embassies in Paris and Tehran: “We have decided that it is desirable to establish a direct American channel to Khomeini’s entourage.”

Secret meetings

Around noon on 15 January, political counsellor Warren Zimmermann of the US embassy in France arrived at a quiet inn at the small town of Neauphle-le-Château, outside Paris, where Khomeini lived. Zimmermann had borrowed his boss’s private Peugeot, which didn’t have diplomatic plates, to avoid being tracked.

“I go in and there was this large dining room empty except for this one guy sitting at a table, and that was Yazdi,” recalled Zimmermann years later in his oral history.

This was Khomeini’s de facto chief of staff, Ebrahim Yazdi, an Iranian-American physician.

A resident of Houston, Texas, Yazdi had already established ties with US officials in Washington through a former CIA operative who had turned into a liberal, anti-Shah scholar, Richard Cottam.

Establishing a direct link with Khomeini was a highly sensitive matter; if revealed, it would be interpreted as a shift in US policy, a clear signal to the entire world that Washington was dumping its old friend, the Shah.

Timeline

1953: Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (the Shah) is restored to power after a US and British-backed coup overthrows the prime minister of Iran

1963: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini rises to prominence for denouncing the Shah

1964: Khomeini is arrested and expelled from Iran. He spends the next 15 years in Turkey and Iraq preaching against the Shah

15 January1979: Khomeini enters into a two-week dialogue from exile in France with the Carter administration

16 January 1979: The Shah flees Iran as the country inches towards civil war

1 February 1979: Khomeini returns to Tehran, where millions line the streets to welcome him as the leader of the Iranian revolution

Earlier in the day, Secretary Vance informed the French government that Washington urgently needed to be in direct contact with Khomeini’s group. The reason: to obtain Khomeini’s support for secret talks in Tehran between Beheshti, and the Shah’s military and intelligence chiefs.

Beheshti had met Sullivan, but out of security concerns, refused to meet with the Iranian generals. So, Washington finally appealed to Khomeini to tell his deputy to show some flexibility “in working out a site for the meeting”, wrote Vance.

A second meeting was quickly scheduled, and Zimmermann was told to pass along that the military had seriously discussed a coup plan upon the Shah’s departure, but General Huyser talked them out of it. The army would “remain calm during that period, provided troops are not provoked,” a cable from the US embassy in Tehran said.

On 17 January, President Carter wrote in his diary that he was pushing hard to keep Khomeini out of Iran. But the next day, his administration told Khomeini that it had no problem with his “orderly” homecoming.

The Carter administration began secret talks with Khomeini with the primary objective of making an elusive deal between the ayatollah and the military. It’s also possible that they wanted to slow down Khomeini’s momentum or read his intentions. But they ended up achieving none of those goals.

Khomeini wanted a decisive victory, not a deal. But a tactical engagement with Washington suited him well. Khomeini, in fact, had a set of key questions to determine Carter’s commitment to the Shah’s regime and the orientation of the Iranian military.

The ayatollah didn’t have to try very hard. America would easily reveal its hand.

‘Protect the constitution’?

By the third time Zimmermann and Yazdi met, they had good news for each other. It was the morning of 18 January 1979. The venue: the same quiet inn near Khomeini’s compound outside Paris.

Khomeini had authorized Beheshti to meet with the generals, Yazdi confirmed. And Zimmermann had an important clarification for the ayatollah.

During their second meeting, Washington had warned Khomeini that his “sudden return” would lead to a disaster, as the Iranian military might react “to protect the constitution” which stated in no uncertain terms that the constitutional monarchy was “unchangeable for eternity”.

But what did “to protect the constitution” mean? Did it mean preserving the institution of monarchy? Or saving the integrity of the military? Khomeini wanted a straight answer.

Put frankly, did the US think the Iranian military had given up on the Pahlavi regime and was “willing to work within the framework of a new democratic republic”?

It took two days for Washington to clarify. The answer, which was kept secret for 35 years, made clear to Khomeini that America was “flexible” about the Iranian political system.

Like most official statements, it began with generalities. The main point was put at the end.

“We do not say that the constitution cannot be changed, but we do believe that the established, orderly procedures for making changes should be followed.

“If the integrity of the army can be preserved, we believe there is every prospect the leadership will support whatever political form is selected for Iran in the future.”

In other words, Washington, in principle, was open to the idea of abolishing the monarchy, and the Shah’s military, whose top brass met daily with General Huyser, would be willing to accept such an outcome provided the process was gradual and controlled.

Khomeini’s biggest fear was that the all-powerful America was on the verge of staging a last-minute coup to save the Shah. Instead, he had just received a clear signal that the US considered the Shah finished, and in fact was looking for a face-saving way to protect the military and avoid a communist takeover.

As usual, Khomeini’s chief of staff “took copious notes” in Persian to be delivered to the ayatollah.

The American diplomat wanted to make sure that the Iranian envoy understood what exactly the message entailed.

“While Zimmermann did cite the points on the constitution in the paragraph, he called Yazdi’s primary attention to the last two sentences of it, which hopefully conveyed to Yazdi a sense of US flexibility on the constitution,” said the US ambassador in France to Washington in a separate cable.

The US had effectively told Khomeini that the military had lost its nerve. “These officers fear the unknown; they fear an uncharted future,” Zimmermann told Yazdi during the same meeting.

To Washington’s relief, the ayatollah pledged not to destroy the military. His emissary urged America not to pull its sophisticated weapons systems out of Iran.

Yazdi also clarified an Islamic Republic would make a distinction between Israel and its own Jewish residents – which had begun fleeing Iran in droves.

“You can tell the American Jews not to worry about the Jewish future in Iran,” he said.

Khomeini and Carter both wished to avoid a violent clash between the military and the opposition. But their aims were fundamentally different.

Carter wanted to preserve the military – which Sullivan once described as an unpredictable “wounded animal” – in order to use it as powerful leverage in the future.

But Khomeini wanted to trap the beast and finish it. The military was a long-term threat to his regime. Its decapitation and destruction was a top priority.

Washington had answered Khomeini’s questions about the future of the monarchy and the orientation of the military. Now, it was the ayatollah’s turn. The Carter administration wanted to know about the future of US core interests in Iran: American investments, oil flow, political-military relations, and views on the Soviet Union.

Khomeini answered the questions in writing the next day – sent back with Yazdi.

It was an artfully-crafted portrait of an Islamic Republic, mirroring what Carter had sketched at a conference of world leaders on Guadeloupe Island earlier that month: an Iran free of Soviet domination, neutral, if not friendly to America, one that would not export revolution, or cut oil flow to the West.

“We will sell our oil to whoever purchases it at a just price,” Khomeini wrote.

“The oil flow will continue after the establishment of the Islamic Republic, except for two countries: South Africa and Israel,” he added.

To develop the country, Iran needed the assistance of others, “in particular the Americans”, Khomeini wrote.

As for foreign investments, the US was likely to have a role. He implied that the Islamic Republic would be interested in buying tractors, not tanks, making it also clear that he had no “particular affinity” for the Russians.

“The Russian government is atheistic and anti-religion. We will definitely find it more difficult to have a deep understanding with the Russians,” Yazdi added to Zimmermann as he delivered the answers.

“You are Christians and believe in God and they don’t. We feel it easier to be closer to you than to Russians,” Yazdi said.

Khomeini also vowed not to destabilise the region.

“Non-interference in other people’s affairs”, he wrote, would be the policy of the future government.

The Islamic Republic, unlike the Shah’s regime, would not act as the policeman of the Gulf, but it would not get into the business of exporting the revolution either.

“We will not ask the people of Saudi, Kuwait, or Iraq to kick the foreigners out,” Khomeini wrote.

The chaos in Iran had alarmed most of Iran’s Arab neighbours, who feared that after the Shah’s downfall armed Marxist groups would take over. A CIA assessment concluded Arab conservatives found it hard to believe Khomeini or a regime associated with his ideas could be a lasting government in Iran.

But the ayatollah would soon eliminate all the Marxist groups that had supported his struggle. Before liquidating the left, Khomeini and his radical followers would push out the moderates, including Yazdi, on the grounds that they were pro-American and not real revolutionaries.

On 24 January, key members of the secret Islamic Revolutionary Council, including a cleric by the name of Ayatollah Mousavi Ardebili – the future Chief Justice of the Islamic Republic who would play a major role in the executions of thousands of political opponents – met with the US ambassador, William Sullivan.

The cleric seemed reasonable. He was a more forceful type, reported Sullivan to Washington, but “no fanatic”.

Three days later, Khomeini himself made a direct appeal to the White House.

“It is advisable that you recommend to the army not to follow Bakhtiar,” wrote Khomeini in his “first first-person” message on 27 January.

Khomeini, in effect, had three requests: smooth the way for his return, press the constitutional government to resign, and force the military to capitulate.

The ayatollah also included a subtle warning that if the army cracked down, his followers would direct their violence against US citizens in Iran.

Still, he made sure to end on a positive note, emphasising the urgent need for a peaceful resolution of the crisis.

Cabled from the US embassy in France after being delivered by Yazdi, the message reached the highest levels of the US government.

In a phone conversation on 27 January, Defence Secretary Harold Brown told General Huyser about Khomeini’s secret message and his discussion with President Carter about it. Brown made it clear to Huyser that Khomeini’s return was a “tactical” matter that had to be left to the Iranian authorities.

The administration was pleased that the ayatollah had agreed to direct methods of communication and wished to continue the talks, according to the newly declassified version of Washington’s draft response to Khomeini.

The proposed response warned Khomeini against setting up his own government, stressing the crisis should be resolved through dialogue with the Iranian authorities.

The text was sent to the US embassy in Tehran for feedback, where it ended up on the shelf, never making it to Khomeini in France.

But it didn’t matter. Soon, the ayatollah would be on his way back to Iran.

Washington had already tacitly agreed to a key part of Khomeini’s requests by telling the military leaders to stay put. General Huyser had told the military that Khomeini’s return alone did not itself constitute a sufficient cause for implementing “Option C”, a direct reference to the coup option.

On 29 January, Prime Minister Bakhtiar, under enormous domestic pressure, opened the Iranian airspace to Khomeini. Bakhtiar had fallen back to his plan B: Khomeini “should be drowned in mullahs” in the religious city of Qom near Tehran.

“This might make him more reasonable or at least less involved in political affairs,” he told the American ambassador, two weeks before being swept away by the Khomeini wave.

Two days before the ayatollah’s arrival, the Shah’s top commander had given specific assurances to Khomeini representatives that the military in principle was no longer opposed to political changes, including in “the cabinet”.

“Even changes in the constitution would be acceptable if done in accordance with constitutional law,” the US embassy was told by a reliable source in the Khomeini camp, according to a cable declassified in November 2013.

The American ambassador was pleased. “Sounds like military have come around to accepting Khomeini arrival and are prepared to cooperate with Islamic movement as long as constitutional norms be respected,” reported Sullivan to Washington.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

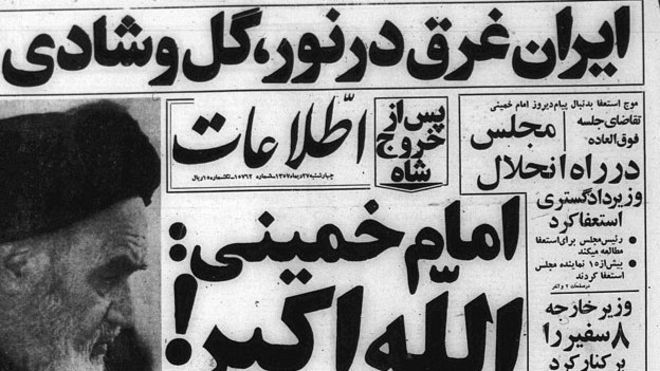

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESKhomeini arrived at Tehran airport on the morning of 1 February, mobbed by thousands of supporters. In a few days, he had appointed a rival prime minister.

By then, the military had no fundamental problems with a change in the form of government, so long as change was done “legally and gradually”, a CIA report, only declassified in 2016, concluded on 5 February, 1979.

At this point, the army’s cohesion had significantly eroded. Many junior officers and conscript soldiers were now with Khomeini.

Soon a mutiny occurred in the air force. The opposition armed itself, and led by radical Marxist groups, attacked army bases and police stations across the capital.

The military leadership had no stomach for an all-out civil war. Behind the back of Bakhtiar, they convened an emergency meeting and declared neutrality. In effect, they surrendered. The Shah’s prime minister ran for his life.

The day Khomeini won his first revolution, President Carter wasn’t in Washington. Over the weekend, he had hit the slopes around Camp David. In the morning of Sunday, 11 February, Mr Carter and his Secretary of State were at a church, temporarily out of reach.

In their absence, the President’s National Security Advisor convened an emergency meeting at the White House Situation Room.

The once-powerful Iranian armed forces had disintegrated, but Brzezinski, who had been among the most pro-Shah voices in the Carter administration, was thinking of Option C, but he was told it wouldn’t be possible, given the state of the military.

Soon, General Huyser was connected to the Situation Room via a secure phone line from Europe. The general would soon face a barrage of public accusations that he went to Tehran to help neutralise the Shah’s military and pave the way for Khomeini’s victory, a charge that he strongly rejected. Most of his reports back to Washington remain classified.

But on 11 February, Huyser’s tone was slightly different, expressing no surprise that the military had taken themselves out of the equation.

“We have always urged the military to make deals,” said Huyser, according to the record of the phone conversation.

“They must have gone to [Mehdi] Bazargan directly,” he said, a moderate Islamist who had already been named Khomeini’s PM.

But all the concessions made by the military weren’t enough for Khomeini. On 15 February four senior military generals were summarily executed on the rooftop of a high school. It was just the beginning of a slew of executions.

Many have come to believe that that the Carter administration – plagued by intelligence failures and internal division – was by and large a passive observer to the rapid demise of the Shah.

But it’s now clear that, in the final stages of the crisis, America had in effect hedged its bet by keeping a firm foot in both camps in the hopes of a soft landing after the fall of the Shah’s regime.

But Carter’s gambit proved to be a massive blunder. The real danger was overlooked, Khomeini’s ambitions were underestimated, and his moves were misread.

Unlike Carter, Khomeini pursued a consistent strategy and played his hand masterfully. Guided by a clear vision of establishing an Islamic republic, the ayatollah engaged America with empty promises, understood its intentions, and marched toward victory.

Less than a year later, Khomeini – while holding the US Charge d’Affaires and dozens of other Americans during the Iranian hostage crisis – declared: “America can’t do a damn thing.”

He then celebrated the first anniversary of his victory with a major proclamation: Iran was going to fight American Imperialism worldwide.

“We will export our revolution to the entire world,” he said, once again asserting: “This is an Islamic revolution.”

A British assessment

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

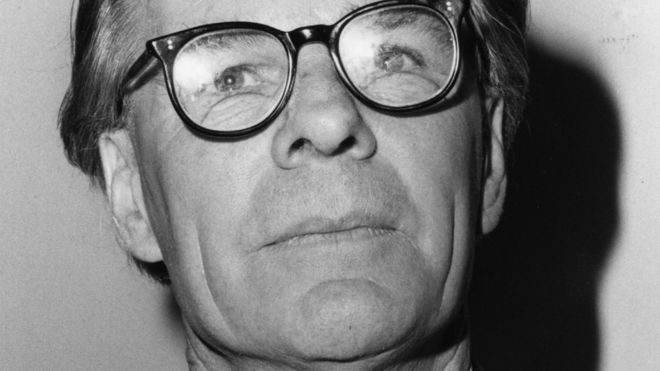

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESBritish ambassador to Iran Anthony Parsons wrote on 20 January 1979, that he had no doubt that the masses of people in Iran wanted “Khomeini’s prescription of an Islamic Republic”.

The problem was, Parsons explained, the military was not psychologically ready for the Khomeini package.

“The generals agreed to the Shah’s withdrawal and to support Bakhtiar on condition that the 1906 constitution including the monarchy was retained,” said Parsons in a cable declassified in November 2013.

“If a transition to a Khomeini dominated republic takes place within days of their attempting the Bakhtiar package, military might well try to react.”

The British Ambassador thought that the sooner Khomeini and the generals got together, and the military transferred their allegiance, the better the chances of saving the country.

Parsons’ frank assessment was also shared with the Carter administration.

US documents show that the cable was in fact on Vice President Walter Mondale’s desk on 27 January 1979 – the same day that Khomeini’s first-person message reached the White House.

BBC

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.