A slide in oil prices is hitting Venezuela hard, raising questions among investors about the South American country’s ability to pay its debts and heightening concerns about the health of developing economies around the world.

A slide in oil prices is hitting Venezuela hard, raising questions among investors about the South American country’s ability to pay its debts and heightening concerns about the health of developing economies around the world.

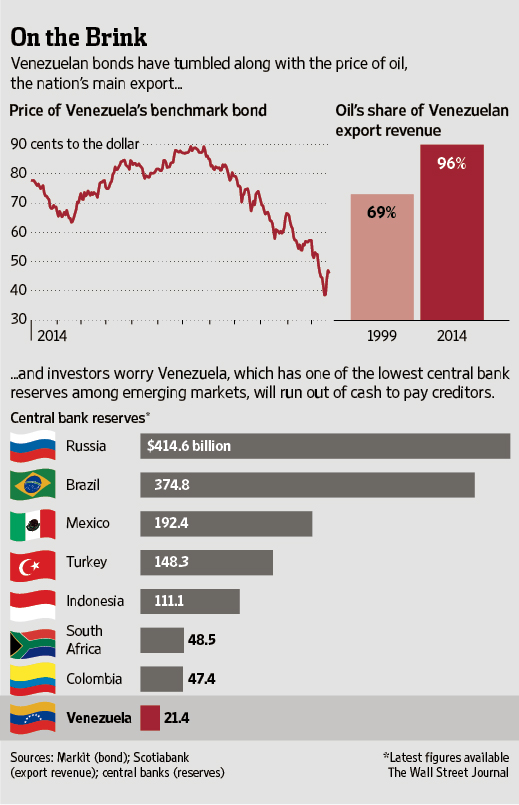

Venezuelan debt was widely held by emerging-market investors until the summer. Many viewed the bonds as a safe bet because the country brought in ample revenue as a major oil exporter. But a nearly 50% drop in the price of crude since mid-June has left Venezuela’s finances in shambles. The price of credit-default swaps on Venezuela debt, a type of insurance, indicate a 61% chance of default in the next year and a 90% chance in the next five years.

The country is an extreme example of the turmoil that sliding prices for oil and other commodities have had on emerging markets, where stocks, bonds and currencies have recently sold off from Russia to South Africa.

Venezuela and its state-run oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela SA, known as PdVSA, issued more debt than any other emerging market between 2007 and 2011. Venezuela and PdVSA have $66 billion in outstanding debt, analysts say.

Venezuela’s woes show how the boom times that drew investors to certain developing economies can quickly evaporate when commodities prices fall. Investors for years were willing to overlook widening budget gaps and rising inflation as they sought higher returns than they could get in developed countries. But now that lower commodities prices have dimmed economic prospects for many countries, money managers are increasingly cautious about where they invest in emerging markets.

“High oil prices helped a lot of these countries cover up their problems, and now the tide is going out and the problems are being exposed,” said Win Thin, global head of emerging-market strategy at private bank Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. “Venezuela will be the first to fall because it’s the weakest…and happens to be the most dependent on oil.”

Last week, Fitch Ratings cut Venezuela’s credit rating deeper into junk territory to CCC from B, citing the Venezuelan economy’s limited ability to respond to the sharp fall in oil prices. However, analysts said a default in Venezuela isn’t imminent. If the country defaults, it would lose access to international markets, which would cut it off from financing to develop its vast oil and gas deposits. A default could also open the door for investors to seize assets of PdVSA, including oil refineries in the U.S. operated through its Citgo subsidiary.

“The cost of defaulting is still too high relative to the benefits,” said Carl Ross, a sovereign-credit analyst at Grantham Mayo Van Otterloo & Co., a $120 billion investment firm that owns Venezuelan bonds. “Investors are expecting some sort of positive policy response that allows Venezuela to muddle through.”

Venezuela’s benchmark bonds tumbled to a record low early last week before rising following a modest rebound in oil prices. The benchmark bond was trading at around 46 cents on the dollar Friday, after falling to around 38 cents on the dollar last Monday. Yields on some short-dated PdVSA bonds are above 40%. Bond yields rise when prices fall.

A Venezuelan default would be unlikely to spill over into other emerging-market countries. Venezuela is regarded as one of the world’s most poorly managed economies, stemming from years of government overspending and a cumbersome currency regime that has deterred investment into the country.

Venezuela has emerged as a potential target for hedge funds that specialize in making money off troubled debt. Some are gambling that oil prices will rebound. Others see an upside in default, in which the government would likely swap outstanding bonds for new debt. With some bonds already below 40 cents on the dollar, the restructured debt might be worth more.

“If you own Venezuelan bonds, you’re not rooting for a restructuring, but you can build a positive argument around it if it does happen,” said A.J. Mediratta, co-president of Greylock Capital Management LLC, which participated in debt restructurings by governments in Argentina and Greece.

Mr. Mediratta said Greylock began buying Venezuelan bonds this summer.

Even before the plunge in oil prices, Venezuela had been in economic crisis. Rigid currency controls and dollar shortages have brought the economy to a standstill and inflation to the highest rate in the world. Polls show President Nicolás Maduro’s popularity at a record low 24.5%.

Analysts said the low approval rating is why Mr. Maduro has taken only piecemeal actions to deal with declining oil prices. They include increasing taxes on luxury products and using a $4 billion loan from China to boost international reserves, which have fallen near decade lows to $21.4 billion. Venezuela’s dwindling reserves make the country more vulnerable than other oil exporters like Russia, which has $414.6 billion in its coffers.

“There is no possibility of a default,” Mr. Maduro said during a televised speech earlier this month, “unless we decide not to pay anymore as part of our economic development strategy…and that is not the strategy that has been developed in these years.”

About 67% of Venezuelans say the government should keep paying off its external debts, according to Caracas-based pollster Datanalisis.

Mr. Maduro hasn’t taken more-drastic steps that analysts say are necessary to right the economy, such as reducing domestic fuel subsidies, loosening foreign-exchange controls and cutting off the cheap oil that Venezuela exports to Cuba and other Caribbean countries.

“What we’re seeing in the markets is a reaction to the complete lack of response from the government” in the face of the economic problems, said Francisco Ghersi, managing director of the Knossos Fund, which specializes in Venezuelan debt.

Wall Street Journal

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.