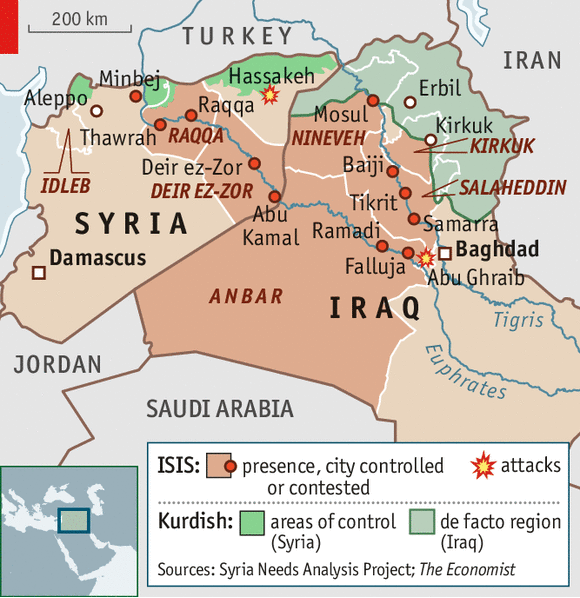

WHOEVER chose the Twitter handle “Jihadi Spring” was prescient. Three years of turmoil in the region, on the back of unpopular American-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, have benefited extreme Islamists, none more so than the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS), a group that outdoes even al-Qaeda in brutality and fanaticism. In the past year or so, as borders and government control have frayed across the region, ISIS has made gains across a swathe of territory encompassing much of eastern and northern Syria and western and northern Iraq. On June 10th it achieved its biggest prize to date by capturing Mosul, Iraq’s second city, and most of the surrounding province of Nineveh. The next day it advanced south towards Baghdad, the capital, taking several towns on the way. Ministers in Iraq’s government admitted that a catastrophe was in the making. A decade after the American invasion, the country looks as fragile, bloody and pitiful as ever.

WHOEVER chose the Twitter handle “Jihadi Spring” was prescient. Three years of turmoil in the region, on the back of unpopular American-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, have benefited extreme Islamists, none more so than the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS), a group that outdoes even al-Qaeda in brutality and fanaticism. In the past year or so, as borders and government control have frayed across the region, ISIS has made gains across a swathe of territory encompassing much of eastern and northern Syria and western and northern Iraq. On June 10th it achieved its biggest prize to date by capturing Mosul, Iraq’s second city, and most of the surrounding province of Nineveh. The next day it advanced south towards Baghdad, the capital, taking several towns on the way. Ministers in Iraq’s government admitted that a catastrophe was in the making. A decade after the American invasion, the country looks as fragile, bloody and pitiful as ever.

After four days of fighting, Iraq’s security forces abandoned their posts in Mosul as ISIS militiamen took over army bases, banks and government offices. The jihadists seized huge stores of American-supplied arms, ammunition and vehicles, apparently including six Black Hawk helicopters and 500 billion dinars ($430m) in freshly printed cash. Some 500,000 people fled in terror to areas beyond ISIS’s sway.

The scale of the attack on Mosul was particularly audacious. But it did not come out of the blue. In the past six months ISIS has captured and held Falluja, less than an hour’s drive west of Baghdad; taken over parts of Ramadi, capital of Anbar province; and has battled for Samarra, a city north of Baghdad that boasts one of Shia Islam’s holiest shrines. Virtually every day its fighters set off bombs in Baghdad, keeping people in a state of terror.

As The Economist went to press, it was reported to have taken Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s home town, only 140km (87 miles) north-west of Baghdad. The speed of ISIS’s advance suggested that it was co-operating with a network of Sunni remnants from Saddam’s underground resistance who opposed the Americans after 2003 and have continued to fight against the Shia-dominated regime of Nuri al-Maliki since the Americans left at the end of 2011.

It was barely a year ago, in April 2013, that ISIS announced the expansion of its operations from Iraq into Syria. By changing its name from the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) by adding the words “and al-Sham”, translated as “the Levant” or “Greater Syria”, it signified its quest to conquer a wider area than present-day Syria.

Run by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, an Iraqi jihadist, ISIS may have up to 6,000 fighters in Iraq and 3,000-5,000 in Syria, including perhaps 3,000 foreigners; nearly a thousand are reported to hail from Chechnya and perhaps 500 or so more from France, Britain and elsewhere in Europe.

It is ruthless, slaughtering Shia and other minorities, including Christians and Alawites, the offshoot to which Syria’s president, Bashar Assad, belongs. It sacks churches and Shia shrines, dispatches suicide-bombers to market-places, and has no regard for civilian casualties.

Its recent advances would have been impossible without ISIS’s control since January of the eastern Syrian town of Raqqa, a testing ground and stronghold from which it has made forays farther afield. It has seized and exploited Syrian oilfields in the area and raised cash by ransoming foreign hostages.

Rather than fight simply as a branch of al-Qaeda (“the base” in Arabic), as it did before 2011, it has aimed to control territory, dispensing its own brand of justice and imposing its own moral code: no smoking, football, music, or unveiled women, for example. And it imposes taxes in the parts of Syria and Iraq it has conquered.

In other words, it is creating a proto-state on the ungoverned territory straddling the borderlands between Syria and Iraq. “This is a new, more dangerous strategy since 2011,” says Hassan Abu Haniyeh, a Jordanian expert on jihadist movements. If ISIS manages to hold onto its turf in Iraq, it will control an area the size of Jordan with roughly the same population (6m or so), stretching 500km from the countryside east of Aleppo in Syria into western Iraq.

In other words, it is creating a proto-state on the ungoverned territory straddling the borderlands between Syria and Iraq. “This is a new, more dangerous strategy since 2011,” says Hassan Abu Haniyeh, a Jordanian expert on jihadist movements. If ISIS manages to hold onto its turf in Iraq, it will control an area the size of Jordan with roughly the same population (6m or so), stretching 500km from the countryside east of Aleppo in Syria into western Iraq.

It holds three border posts between Syria and Turkey and several more on Syria’s border with Iraq. Raqqa’s residents say Moroccan and Tunisian jihadists have brought their wives and children to settle in the city. Foreign preachers have been appointed to mosques. ISIS has also set up an intelligence service.

The regimes of Mr Assad in Syria and Mr Maliki in Iraq have played into ISIS’s hands by stoking up sectarian resentment among Sunni Arabs, who are a majority of more than 70% in Syria and a minority of around a fifth in Iraq, where they had been dominant under Saddam Hussein. But Mr Assad has cannily left ISIS alone, rightly guessing it would start fighting against the more mainstream rebels, to the regime’s advantage. And he has highlighted the horrors of ISIS to the West, as the spectre of what may come next were he to fall.

Two ogres versus a bunch of thugs

Mr Maliki has been less brutal but more crass than Mr Assad. By the end of 2011 American forces had almost eradicated ISI, as it still was, in Iraq. They did so by capturing or killing its leaders and, more crucially, by recruiting around 100,000 Sunni Iraqis to join the Sahwa, or Awakening, a largely tribal force to fight ISI, whose harsh rules in the areas they controlled had turned most of the people against it.

But after the Americans left, Mr Maliki disbanded the Sahwa militias, breaking a promise to integrate many of them into the regular army. He purged Sunnis from the government and cracked down on initially peaceful Sunni protests in Ramadi and Falluja at the end of last year. Anti-American rebels loyal to Saddam and even Sahwa people may have joined ISIS out of despair, feeling that Mr Maliki would never give them a fair deal. In 2012 Tariq al-Hashemi, the vice-president who was Iraq’s top Sunni, fled abroad, and was sentenced to death in absentia. Sunnis feel they have no political representation, says Mr Haniyeh. “ISIS and al-Qaeda are taking advantage and appropriating Sunni Islam.”

Some countries in the region, loathing Mr Assad’s brutality against civilians and Mr Maliki’s brand of Shia triumphalism, initially indulged ISIS. Turkey let a free flow of foreign fighters cross its borders into Syria until the end of last year. Some Gulf states, such as Kuwait and Qatar, were slow to clamp down on private citizens who have funded ISIS and at first tolerated or even applauded its sectarian ire.

The carnage in Iraq, though not as numerically horrendous as in Syria, has been growing ferociously, leaving 5,400 people dead this year alone. According to some estimates, ISIS has been responsible for 75% to 95% of all the attacks. It has organised a number of prison breaks, such as one in 2013 from Abu Ghraib, whence several hundred jihadists escaped to join the fray; this week ISIS may have freed some 2,500 hardened fighters from jail in Mosul.

Whether in Iraq or Syria, ISIS has sought to terrify people into submission. On June 8th, as a typical warning to others, it crucified three young men in a town near Aleppo for co-operating with rival rebels. It has kidnapped scores of Kurdish students, journalists, aid workers and, more recently, some Turkish diplomats.

Even al-Qaeda has deemed ISIS too violent. Ayman Zawahiri, leader of the core group, has long disagreed with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, ISIS’s leader, warning him that ISIS’s habit of beheading its opponents and posting such atrocities on video was giving al-Qaeda a bad name.

So far ISIS has been effectively challenged only by fellow Sunnis. It is locked in battle with Jabhat al-Nusra, which al-Qaeda recognises as its affiliate in Syria. The two groups are tussling over Deir ez-Zor, a provincial capital between Raqqa and Anbar, leaving 600 fighters dead in the past six weeks. Since the start of the year, mainstream Syrian rebel groups, who at first welcomed ISIS for its fighting ability, have battled against it, forcing it out of areas in the north-western province of Idleb and the city of Aleppo. Kurdish forces in the north-east have done the same.

Some reckon that ISIS’s recent push in Iraq may be intended to bolster its rearguard, enabling it to replenish its coffers and armoury, before striking back at the rebel opposition in Syria. The more moderate rebels are ill-equipped to fight for ever against ISIS; they say that half their forces have already been diverted from the fight against Mr Assad to hold ISIS at bay.

The forces best equipped to face down ISIS may be Kurdish ones: the Peshmerga guerrillas, who have protected Iraq’s autonomous Kurdish region for the past two decades, and the People’s Protection Units, better known as the YPG, the armed wing of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which dominates north-eastern Syria. The Kurds’ regional government in Iraq has mobilised its forces on the east side of the Tigris river, which runs through Mosul, and may well block ISIS from heading east and north into Kurdish territory; on June 12th the Kurds captured all of Kirkuk city from fleeing Iraqi forces. Yet Mr Maliki may have to call on the Kurds to help him out against ISIS.

Don’t come back home

Western governments are fretting about the threat from some of their own citizens who have joined the likes of ISIS and may come home to make trouble. On May 28th Barack Obama asked for an additional $5 billion for counter-terrorism programmes. ISIS people have not hidden their intention to carry out attacks in the West in the name of jihad. The man accused of killing four men dead in Belgium’s Jewish museum on May 24th was a veteran of Syria’s war. ISIS runs training camps in the desert of eastern Syria. Jordan and Turkey are worried too.

But few governments, except perhaps Iran, are keen to arm Mr Maliki’s increasingly nasty and incompetent regime. Last year the United States did agree to sell Iraq more weapons, including F-16 fighter jets. The threat of terrorism against the West may prod Western governments into giving more arms and help to the anti-ISIS Syrian rebels. But helping Mr Maliki more wholeheartedly is another matter. Mr Obama has refused to hit ISIS with drones.

In the long run the biggest hope for containing ISIS lies in its lack of a broadly popular base. After all, al-Qaeda itself dismally failed to capture Arab minds during the Arab spring. Most Syrian and Iraqi Sunnis do not wish to be ruled by extremists. Mosul and other areas may yet return to the hands of the government. Yet Syrians and Iraqis are both trapped between dictators on the one hand and extremists on the other. An unhappy choice

The Economist

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.