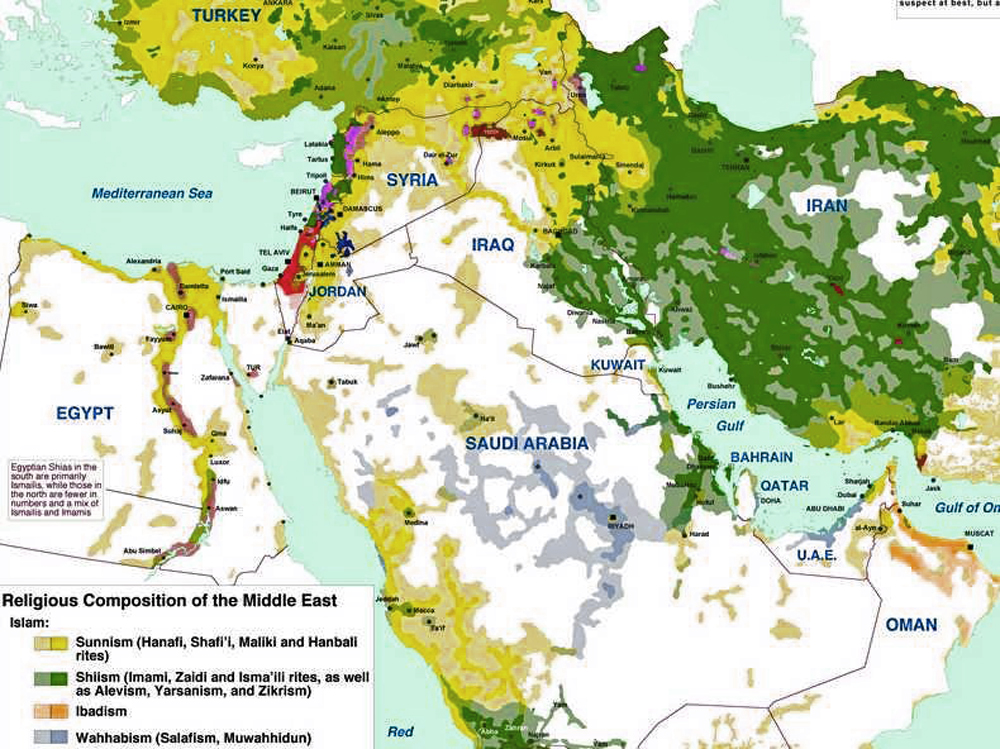

Saudi Arabia’s proxy war against Bashar al-Assad is popular among a mostly Sunni Muslim public enraged by the killings of their co-religionists in Syria. Among the kingdom’s Shiite minority, many worry that the anger will eventually be directed toward them.

Religious leaders regularly speak out against Assad, whose family follows a branch of Shiite Islam and is backed by the region’s main Shiite power and Saudi Arabia’s biggest rival, Iran. Abdulrahman al-Sudais, the imam of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, has called the Syrian president a force for “hatred, extremism and criminality.” Saudi Arabia is funding the Sunni-led rebels fighting to oust Assad.

While denunciations of Assad are widespread in the West too, in Saudi Arabia there are signs that the Syrian war is encouraging a more general criticism of Shiites. Three popular clerics posted a video on YouTube to coincide with Ashoura, the main Shiite festival, calling their celebration “inappropriate.” Mohammed al-Arefe, who has more than 7 million Twitter followers, said in the film that the festivities “would not please God.”

For the Saudi Shiites, who mostly live in the Eastern Province among the world’s largest oil fields, such messages add to a sense of oppression that has exploded into unrest in the past. Shiites instigated the most serious protests to break out in the kingdom since 2011, when the Arab Spring uprisings laid bare a growing religious divide across the Middle East.

‘Sectarian Terms’

“The Syrian conflict has increased our concerns, because it’s being talked about in sectarian terms,” said Mohammed al-Nemer, a local businessman and editor of a quarterly journal on Shiite culture. His brother, a Shiite cleric, was arrested in July last year and is still in detention.

Over lunch at a roadside restaurant in Qatif in Eastern Province, surrounded by oil pipelines, al-Nemer says he’s worried that the Syrian conflict may lead to a backlash similar to the one that followed the Iranian revolution in 1979. He said that was the worst time he can recall for Saudi Shiites.

Tawfiq AlSaif, an activist from Qatif, also remembers that era, when he says he was forced to flee the country. AlSaif said in a phone interview the Syrian war has “added fuel to an already burning fire” caused by Sunni-Shiite violence in other countries in the region including Iraq, Bahrain and Yemen.

Saudi troops in March 2011 helped crush a revolt by Shiites in neighboring Bahrain, where many Saudi Shiites have cultural and family ties. Crude prices rose more than 10 percent that month amid concern that protests would spread to Saudi Arabia.

‘Getting Worse’

Unrest inside the kingdom has sometimes turned violent, too. In Awwamiya in Eastern Province, a traffic circle is dotted with pictures of young men killed during skirmishes with security forces.

Saudi Shiites say they’re denied government jobs, discriminated against because of their religion, and unfairly treated as a potential enemy within. The State Department said in its latest human rights report on Saudi Arabia, a longtime U.S. ally, that Shiites “suffer social, legal, economic, and political discrimination.”

Saudi authorities typically blame Iran for stirring up trouble among the Shiites. They’re often viewed as a threat during times of regional unrest, said Paul Sullivan, a Middle East specialist at Georgetown University in Washington.

“The Saudis are quite concerned, as they should be, about the possible spillover of increased violence and dissent in response to events in Syria and Bahrain,” he said. “Tensions between the Sunnis and Shiites are not subsiding, and seem to be getting worse.”

Free Food

Jafar al-Shayeb, a Shiite member of Qatif’s Municipal Council, says Saudi authorities always view Shiites “from the security perspective, which is very short-term. It is always creating tension.”

Al-Shayeb cites the crackdown by police and security forces on Shiite protests since 2011, which meant that the protest movement “wasn’t able to deliver its message” and lost public support.

There are still checkpoints on roads into Qatif and Awwamiya, though the presence is less visible than two years ago. Prince Saud Bin Nayef, who took over as the province’s governor in January, has taken steps to ease tensions.

On the streets during this month’s celebration of Ashoura, celebrants were provided with free food and drinks at stalls shrouded in black. “The situation in Qatif is quiet and okay,” Interior Ministry spokesman Major General Mansour al-Turki said by text message in response to questions.

‘Red Lines’

Shiites are also sharing the benefits of King Abdullah’s spending plan, worth more than $500 billion, to lower the 12 percent unemployment rate nationwide and ward off unrest. It has created jobs, and given many Shiites the chance to study abroad.

AlSaif said employment opportunities for Shiites are “far better than before.” He also said he detects some easing of restrictions on criticizing government policies. “I keep going beyond the so-called red lines,” he said in a Nov. 6 phone interview. “I haven’t received anything that can be translated as a message to stop.”

Differences between the Sunni and Shiite communities are sometimes discussed amicably. At a dinner this month on a date farm in the al-Hasa oasis, young men from both sects discussed the changes under the new governor as they smoked water-pipes stuffed with apple-flavored tobacco. There was friendly disagreement over their success, with Shiites stressing the limits of change.

More Acceptable

They also discussed Syria. One of the men, who like all of them declined to be identified, said the war has made it more acceptable to express hostility toward Shiites.

Al-Shayeb, the Shiite councilor, said there’s plenty of mixing between the communities, though he said that more radical Sunni groups elsewhere in the country are less tolerant of Shiites. He also welcomes measures such as the scholarships for overseas study, and says there’s no discrimination against Shiites in such programs.

Yet, says al-Shayeb, there’s still no “serious and genuinely positive” move by the central government to address Shiite demands for equal civil rights. That leaves the communities “open to any regional changes, in Bahrain, in Syria, in Iraq and Iran.”

By Glen Carey

Originally published on Bloomberg website

Top photo: Tawfiq AlSaif, a Saudi Shiite activist from Qatif, said in a phone interview the Syrian war has “added fuel to an already burning fire” caused by Sunni-Shiite violence in other countries in the region including Iraq, Bahrain and Yemen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.