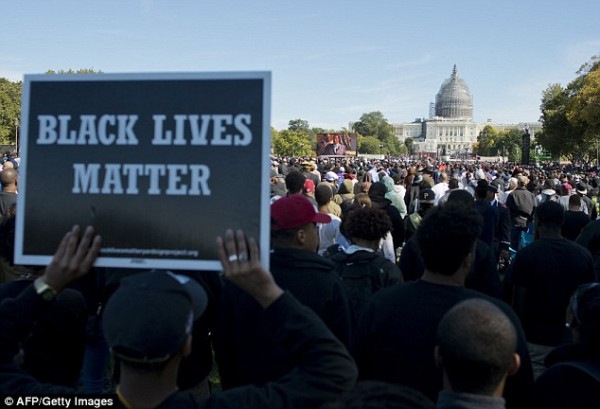

Thousands of black men, women and children gathered on the Mall on Saturday to demand justice at a time of growing anger and fraying tensions in African American communities across the nation over the killings of young black men by police.

By noon Saturday, the crowds had swelled just beyond the stage at the west front of the Capitol, with onlookers watching on several jumbo screens set up on the lawn. Some people sat on lawn chairs and others on blankets to listen to the speakers, including Louis Farrakhan, the leader of the Nation of Islam, which sponsored the “Justice or Else” rally.

The event marked the 20th anniversary of the Million Man March in 1995, when hundreds of thousands of black men rallied on the Mall in a powerful display of protest. Although Saturday’s crowd was far smaller, the spirit of the first movement was echoed by those who addressed the audience.

But the speakers also pointedly tied the struggle of the black community to modern-day incidents. Tamika Mallory, a national organizer of the rally, recited a list of young black men who have been killed by police in recent years, including Tamir Rice of Cleveland, Michael Brown of Ferguson, Mo., and Eric Garner of Staten Island.

“Twenty years ago, the death of Tamir Rice would have fallen on deaf ears and been left for the police to write a false report, not broadcast for the world to know,” Mallory told the crowd. “Michael Brown’s body would have only traumatized the community, rather than wake up the people.

“America, we can’t breathe,” Mallory said, echoing the phrase that Garner uttered while being held in a chokehold by police in July 2014 and that has been appropriated by the civil rights movement.

The peaceful rally was a reminder that seven years after the election of the nation’s first black president, enormous frustration remains among segments of the African American community about progress on civil rights.

President Obama, who has spoken out about gun violence and the mistrust between police and the black community, was attending Democratic fundraisers in California on Saturday. His administration has sought to balance a call for reforms among the tactics of local law enforcement agencies with support for police departments to help integrate them more fully into their communities.

The only images of him and first lady Michelle Obama at the rally were on tote bags being sold by vendors.

The mothers of Sandra Bland — a black woman found dead in her jail cell in Waller County, Tex., in July after an altercation with a police officer — and Trayvon Martin — a black teenager fatally shot by a community watch volunteer in 2012 — appeared together onstage with relatives of other shooting victims. Bland’s death was ruled a suicide by local authorities, and Martin’s killer was acquitted of second-degree murder charges; however, the circumstances around both deaths have angered black leaders.

“This is about human rights,” said Sybrina Fulton, Martin’s mother. “We will not continue to stand by anymore.”

Farrakhan, who had also organized the 1995 rally, spoke for more than two hours — as he did 20 years ago. He delivered a rambling address that challenged the participants to work at self-improvement and pledge their faith in God. But he also criticized the federal government for failing to protect and provide for the public, especially the underclass.

“There’s no government on this earth, not one, that can give the people what the people desire of freedom, justice and equality,” he said. “You are yearning for something the government can’t give you.”

Though his organization is not connected to newer movements such as Black Lives Matter that have sprung up in response to the recent violence, Farrakhan made the link by suggesting this period represents a new flashpoint in the civil rights struggle.

“This is not a moment. This is a movement,” Farrakhan said. “When the brothers and sisters arose in Ferguson, you didn’t have any money; you had a principle, a principle you were willing to suffer for that you felt was bigger than yourself and your life and your withstanding of pain.”

Signs of the community’s frustration were displayed on T-shirts reading “Black Lives Matter” and on posters reading “Straight Outta Patience.” One man wore a “Hands up, don’t shoot” T-shirt, marking the rallying cry in Ferguson after residents and police clashed violently in the streets in the wake of Brown’s shooting death in August 2014.

There were more young adults on Saturday than there were 20 years ago at the Million Man March and, proportionally, more women. Onstage, there were few national black leaders and politicians, such as Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton, who were not in attendance.

Some spoke about other calls for justice — for Native Americans and for congressional representation for D.C. residents.

Dennis Muhammad, 45, of Charleston, S.C., arrived on a bus with 55 members of his community early Saturday. Muhammad came to stand with the others “for the cause of justice for all of our people, especially those of our people that have been victims of overzealous police work or brutality.”

He mentioned Walter Scott, a South Carolina man killed in a police shooting in North Charleston in April whose family recently received a $6.5 million settlement from the city.

Norris Henderson came to Washington with a group of former offenders from New Orleans.

“Twenty years ago, I watched this on TV from a jail cell,” Henderson said. “The last thing that they said at the march was ‘Don’t forget the brothers on the inside.’ ”

Also in the crowd was Shon Terrell, 46, who works for the Justice Department in Atlanta. He pointed toward the Washington Monument to show his friends how far back the crowd stretched 20 years ago.

“You could feel the energy,” Terrell recalled. “Twenty years later, I had to come. I was compelled again. It’s part of me.”

WASHINGTON POST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.