On the tenth anniversary of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s rise to power, a prominent human rights group has accused him of doing too little to change his country’s long-running history of government oppression and abuse.

While Assad has used the US invasion of Iraq and the “chaos” surrounding his country in the Middle East to justify his tight control over the limited freedom of expression allowed in Syria, Human Rights Watch (HRW) says that “a review of Syria’s record shows a consistent policy of repressing dissent regardless of international or regional developments”.

Assad’s state security forces have jailed at least 92 human rights activists and 25 bloggers and journalists in the past 10 years, according to a report released by the organisation on Friday.

The report, which refers to Assad’s time in office as “a wasted decade,” details the 117 cases and their outcomes, which ranged from three months’ imprisonment to 12 years, but notes that the number of jailed writers and activists is probably far larger than what HRW was able to discover.

Frozen ‘Spring’

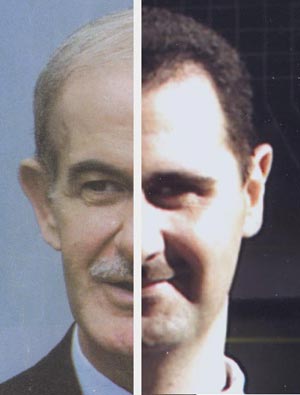

Assad succeeded his father Hafez as president in July 2000. The elder Assad, a high-ranking member of the Baath party, had come to power in 1971 and presided over a police state that used violence and forced disappearances to repress Islamists and other dissidents within the country.

Assad succeeded his father Hafez as president in July 2000. The elder Assad, a high-ranking member of the Baath party, had come to power in 1971 and presided over a police state that used violence and forced disappearances to repress Islamists and other dissidents within the country.

In his inaugural address, Assad gave hope to reform-minded Syrians and outside observers by speaking of a need for “democracy” and “transparency”.

“It was as if a nightmare was removed,” a human rights activist who spoke with HRW said in 2006.

In the year after Assad’s inauguration, civil society in Syria experienced a small and modest renaissance. The period came to be called the “Damascus Spring”; some 21 informal groups began to gather in private homes to discuss human rights and reform efforts, according to the report.

But that rebirth came to an end in August 2001 with the jailing of Ma’mun al-Homsi, a member of the Peoples Assembly who was known for criticising the government. Within a month, Syrian security forces had arrested 10 opposition leaders, including two members of parliament.

“Hopes for political change of course dawned early when [Assad] first took power,” Paul Salem, the director of the Carnegie Middle East Center, told Al Jazeera.

“But [they] quickly were dashed and have not been revived. There’s been no real progress in internal politics.”

Though Assad did away with an old ban on independent newspapers, he replaced it with a heavily restrictive Press Law in September 2001. The two private dailies currently operating in the country are both run by businessmen who are close to the government: One man is reportedly Assad’s cousin, while the other is the son of security chief General Bahjat Suleiman, according to HRW.

Expansive powers

Since the “Damascus Spring,” Assad has done little to follow through on the rhetoric of his inaugural address, emphasizing instead economic progress and stability over the improvement of civil society, the HRW report says.

Syrian security services have proven willing to utilise the broad powers of arrest provided to them under the country’s penal code, which criminalises acts such as “weakening the national sentiment” or “inciting sectarian, racial, or religious strife”. And unlike the police, agents of Syria’s General Intelligence Division, the Idarat al-Mukhabarat al-Ama, are immune from prosecution unless the director of the agency allows it.

Since none of the country’s non-governmental organisations are officially licensed or authorised to exist, it’s easy for security forces to exercise their expansive powers at will, the report says.

“Lack of registration is like a sword hanging over our necks,” one human rights lawyer told HRW in 2006.

A legacy continued

Although Assad and his wife, Asma, have both made encouraging statements about reform, and Assad has taken steps toward improving the treatment of detainees, Syria’s behaviour toward political prisoners and the Kurdish minority still follows the beat of the previous government, according to the report.

In November 2000, Assad closed one prison holding “numerous” political inmates and transferred 500 other political prisoners from Tadmor, in the country’s eastern desert, to Sednaya, which reportedly offers better conditions.

But security forces continue to “regularly hold detainees incommunicado,” HRW says. In August 2008, they detained 13 men from Deir al-Zor for alleged Islamist ties, and the government has yet to disclose exactly why most of them were arrested, whether they will be charged and where they are currently located. One arrested man’s body was returned to his family after he died, though his relatives were only allowed to see his face before he was buried.

Meanwhile, the government continues to avoid rectifying a 1962 census that stripped some 120,000 Kurds of their citizenship. The number of stateless Kurds has grown to around 300,000 in the intervening decades, making it difficult for nearly 18 per cent of the country’s largest non-Arab ethnic minority to get jobs, register weddings and obtain state services.

The state has banned the teaching of Kurdish in school and regularly disrupts Kurdish festivals, such as Nowruz, the New Year celebration, the report says.

Kurdish protests throughout northern Syria in March 2004 were met with state violence, leaving 36 dead, 160 wounded and more than 2,000 arrested and possibly subject to torture and ill treatment, according to HRW.

‘Wasted decade’

Ziad Hafez, the editor of Contemporary Arab Affairs, told Al Jazeera that while he did not condone Assad’s “stifling of freedom of expression,” he believes that the opposition moved too quickly in the early years of the new government.

After the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, reformers were emboldened and “took positions that were not really nationalistic,” Hafez said.

“You also have to understand that when the regime is feeling attacked and surrounded by foreign powers, to be what we’d call a fifth column is not exactly the best position to be opening up the political scene on the domestic side.”

In its report, HRW theorises that Assad may have been frightened by the fast pace at which independent groups began to express themselves openly during the “Damascus Spring,” and that this prompted a reversal.

Alternatively, the report notes, Assad could have been pressured into backtracking by an entrenched “old guard” that feared losing power.

By Evan Hill- Al Jazeera

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.