By:Jeremy Arbid

By:Jeremy Arbid

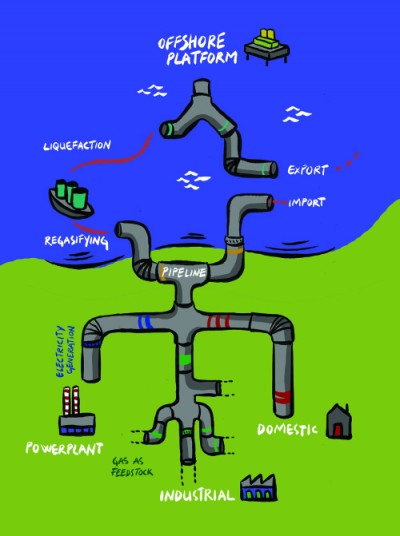

When Lebanon moves forward toward extracting its potential oil and gas resources in the country’s coastal waters, it will do so with the intention of powering industrial manufacturing and investing in infrastructure for small and medium sized enterprises (SME) integrating them with operating oil companies, creating an industry of support and ancillary service companies.

The Lebanese Petroleum Administration (LPA) has repeatedly indicated this intention in its vision for Lebanon’s oil and gas sector, saying the crown jewel is not the lucrative extraction of resources, but rather encouraging manufacturing, industrial localization and SME integration.

Difficulty to localize

Though revenue from the sale of potential petroleum resources could be significant, the lasting value might come in powering industrial manufacturing and encouraging the integration of SMEs into an oil and gas value chain. “It is a very large area of opportunity and — when we talk about SMEs — quite a large chunk of revenues depend on the services provided,” says Georges Chehade, a partner with Strategy& and the firm’s leader of the energy, chemicals and utilities practice for the Middle East. “There will be a lot of opportunities to localize,” he adds.

As the sector matures, developing a value chain will hold huge potential for employment generation and investment opportunities across industries, infusing wealth into the Lebanese economy that could last well into this century and perhaps beyond, explains Chehade. However, the initial phases — exploration and development of reservoirs — will only see limited integration of local companies in servicing the operating oil companies. Exploration during the first licensing round, which typically lasts three to five years, “is a difficult phase to localize and mainly will rely on the resources and bases that these [companies] will have somewhere else in the region,” says Chehade. Operating oil companies that might be awarded contracts for exploration most likely will rely on existing resources in the region. For example, “they might have rigs in the Mediterranean that they will bring in order to drill these [wells],” explains Chehade.

Though the exploration phase might hold only limited opportunities for local companies to integrate services and supply materials and products to the operating companies, it is at the development and production stages where SMEs could begin infusing their products and services within the sector. It is at these stages that two types of activities will become in demand — engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) services, and oilfield services (OFS).

Less-technical services, materials and products could be supplied by existing or newly established Lebanese companies

“These are two big buckets of services that will be required,” Chehade points out, articulating the importance of EPC and OFS companies. These companies will fulfill the main supply chain requirements of the operating oil companies, offering technical services such as the servicing of drilling rigs, pipe laying and the construction of refining infrastructure. Most likely, large OFS companies will enter the Lebanese market to meet demand; examples include Schlumberger, Baker Hughes and Halliburton, all of whom have shown interest by sponsoring Lebanese oil and gas conferences. These companies might use materials supplied by the Lebanese market. For instance, cement from Lebanese factories might cost less due to shipping expenses and the same could be the case with other materials or for the laying of pipelines which could be done using local firms. This point is particularly pivotal given the local content strategy articulated by the LPA.

Less-technical services, materials and products could be supplied by existing or newly established Lebanese companies. Chehade says this includes everything required to cater to the needs of offshore production including marine vessels or helicopters for transportation to drilling rigs, food catering or the construction of housing for workers to name but a few.

A part of the local content stipulations in model exploration contracts are employment requirements compelling companies to hire 80 percent of their workforce from the local labor market. Localizing employment, Chehade says, “will definitely encourage the development of an industry and increased localization of these steps of the value chain.” But in addition to labor force requirements, the local content policy will also give preference to Lebanese contractors to provide needed goods and services to companies throughout the petroleum industry, into ancillary industries. Specifically, there will be a preference for Lebanese services even if they’re up to 10 percent more expensive, and for goods up to 5 percent dearer. The latter preference will only apply to goods actually produced in Lebanon, according to the LPA.

Impact on the price of fuel

Confirming commercial quantities and the quality of findings through exploratory drilling will benefit Lebanon in at least two other significant ways. First, if and when viable quantities of natural gas are found, industries and factories can use the fuel to power manufacturing.

In an August interview with Middle East Strategic Perspectives, a local consulting firm, Minister of Energy and Water Arthur Nazarian discussed how the reduction of heavy fuel oil imports — and relying on natural gas if Lebanon discovers the resource in coastal waters — could benefit industries through a lower “energy bill which has been so far one of the major impediments to competitiveness on the international markets for Lebanese products.” (See this month’s special report on Lebanese industry)

Presently, Lebanon has little heavy industry because there is limited availability of fuels to power manufacturing and electricity supply in the country is intermittent, requiring small factories to purchase generators. The high cost of energy and low reliability of access to electricity in Lebanon reduces the country’s manufacturing competitiveness compared to many of its neighbors in the Middle East where energy flow is reliable and, in some cases, the cost of fuel is subsidized. At a conference in September, The Daily Star reported, Industry Minister Hussein Hajj Hassan stated that “Lebanese industrialists have in the past years been alone in the face of competition from neighboring countries where the industrial sector is supported in terms of subsidized electricity, export and proper and affordable infrastructure.”

If Lebanon begins producing natural gas, the LPA tells Executive, “Lebanese industry, which suffers from high energy bills that are impeding its productivity and growth, will be provided with secure, clean natural gas.”

The forecasting of domestic demand, encompassing the needs for residential use, electricity generation and industrial manufacturing are calculations the LPA has begun to compile. Electricity generation will require 0.2 trillion cubic feet of gas annually, the LPA has said during conference presentations, though figures for residential and industrial demand are not presently available.

Subsidizing fuel demand for industrial use in manufacturing is a tricky issue. Egypt, for example, aggressively subsidized fuel and under-forecasted demand growth for industrial use, a lesson the LPA has noted and will look to avoid (see the special report overview).

Developing a petrochemical industry

“Lebanese industry, which suffers from high energy bills that are impeding its productivity and growth, will be provided with secure, clean natural gas”

Confirming quantity and quality of natural gas will also give a clearer picture for developing a downstream petrochemical industry. Lebanon will know more in three to five years, Chehade points out, adding, “It’s premature to think now about what could happen in downstream because we don’t know what sort of gas is down there and the type of gas will determine the application, especially in the petrochemical streams.”

The versatility of natural gas is exceptional. The fuel is a common feedstock to produce multipurpose chemical products like synthetic ammonia and urea, which are most widely used as fertilizer for agriculture. Ammonia and urea are also ingredients used to manufacture industrial explosives; catalytic converters to reduce the exhaust from combustion engines; it’s an ingredient in many household products like hair conditioners, tooth whiteners and dish soap; it’s sometimes used as a cloud seeding agent to modify precipitation and has been used as an additive to enhance cigarette flavor. It also has many medical uses in dermatological products to rehydrate the skin and as a diuretic. It can also be used as a raw material to produce decorative laminates, textiles, paper, foundry sand molds, wrinkle resistant fabrics and adhesives. Simply put, natural gas is a very important feedstock for the chemical industry.

Adding value

Because Lebanon is still in such an early stage of the exploration process, the pieces of an oil and gas value chain have not fallen into place yet. Mapping out how a web of companies will be interconnected and the way revenues, goods and services will flow both to the oil and gas industry and into secondary industries is an extensive task that the LPA plans to, perhaps with consultation, undertake. SMEs will perform integral roles and, as companies reach higher levels of sophistication in the services and goods supplied, it will be important to plug SMEs into regional and global value chains.

But integrating SMEs into regional and global value chains is no simple feat. A 2010 report published by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) found that “while some governments have industrial policies and may promote certain economic sectors, they have been less supportive of SMEs … nevertheless, there is growing awareness of the contribution of SMEs to income, employment and exports.” The report broadly recommended governments support SME innovation and integration into evermore sophisticated value chains to enable SMEs to meet international quality standards through highly specialized training programs for workers and financial measures and instruments to support SME innovation and technology.

The benefits to Lebanon in doing so are self-explanatory — more manufacturing, more jobs, more products for export — while the benefits to big, international companies are huge. A 2007 International Finance Corporation report in collaboration with Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government noted that “in developing countries, business linkages with local small–medium enterprises — including procurement, distribution and sales — offer the transnational corporations an avenue to reduce input costs while increasing specialization and flexibility.” Similarly, in its 2006 World Investment Report, UNCTAD identified 77,000 transnational corporations that in 2005 had counted 770,000 local partners which “generated an estimated $4.5 trillion in value-added, employed some 62 million workers, and exported goods and services valued at more than $4 trillion.”

These reports indicate the importance of integrating local suppliers of goods and services into regional and global value chains, the effects of which produce ever more sophisticated products and services with big impacts on local and regional economies and international trade.

What potentially lies beneath Lebanese waters could translate into big gains for Lebanese industries and future entrepreneurs. If the country does find oil and gas resources — offshore prospectivity is high — then industry and SMEs powered by these fuels will flourish.

Executive magazine

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.