Israel’s government is concerned that the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague will issue arrest warrants against senior Israeli officials in relation to the war in Gaza. Those under suspicion could include Binyamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, members of his cabinet and generals in the Israel Defense Forces. The ICC has not said it is considering such a move. Yet Mr Netanyahu felt the threat serious enough to state on April 30th that any warrant “would be an outrage of historic proportions”. The ICC’s chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, warned that threats to “retaliate” against the court could undermine its impartiality. On what grounds would the ICC issue such warrants, and what would be the consequences?

Several accusations of war crimes have been made against Israel during the war. The International Court of Justice, for instance, which is not connected to the ICC, has conducted inconclusive hearings on whether Israel is carrying out a genocide in Gaza. Unlike that court, the ICC deals with individuals rather than countries.

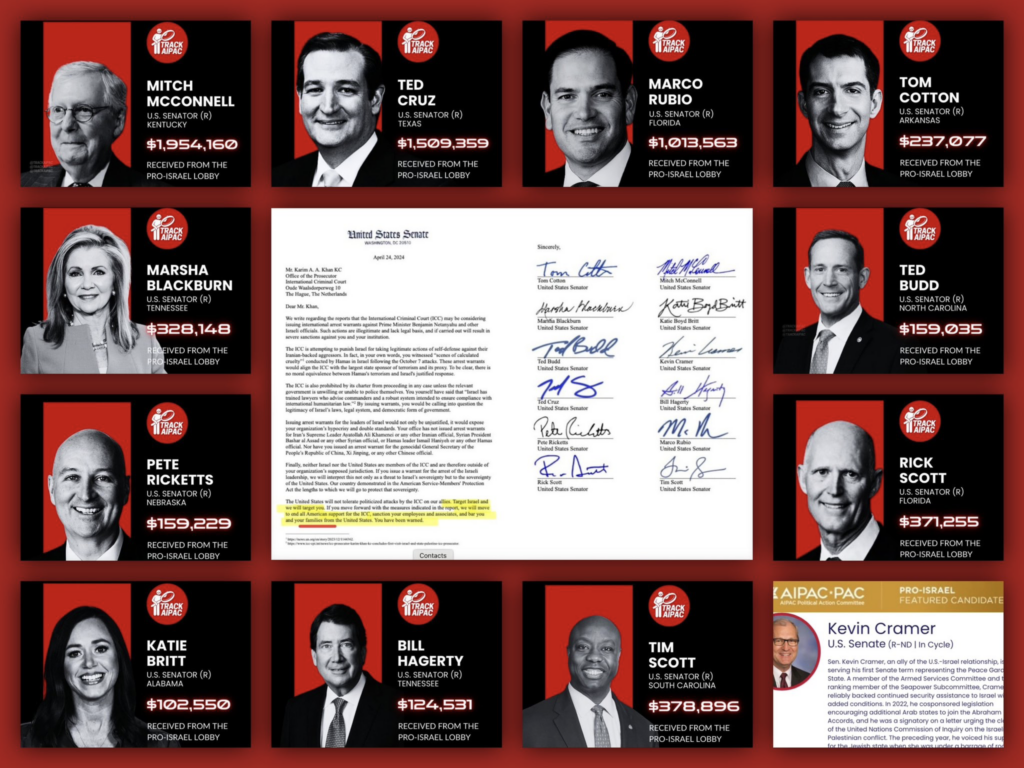

Read the letter from 12 Republican senators threatening ICC chief prosecutor @KarimKhanQC with "severe" consequences for him, his family & staff if he goes ahead with an arrest warrant for Netanyahu. "You have been warned."

— Mehdi Hasan (@mehdirhasan) May 6, 2024

Oh and subscribe to Zeteo too:https://t.co/pVvXi4IB6C pic.twitter.com/aXfKH03T16

The list of those it has charged in its two-decade history is a 54-name-long litany of infamy. It includes Muammar Qaddafi, the Libyan tyrant for whom an arrest warrant was issued on charges of crimes against humanity five months before his death in November 2011; Omar al-Bashir, a former dictator of Sudan, indicted in 2009, but still “at large”, as the ICC website puts it; and Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, for whom the ICC issued an arrest warrant in March 2023, for the illegal deportation of children from Ukraine.

The US senators that threatened ICC

It is not a list that Mr Netanyahu would want to join, even—or perhaps especially—if the ICC also indicts senior Hamas leaders, as seems likely. The perception of moral equivalence with Israel’s foes would be hard for him to stomach.

As for the alleged crimes, Israeli legal officials suspect the ICC is investigating the obstruction of humanitarian supplies into Gaza, which international aid organizations claim has brought parts of the enclave to famine. The ICC could be considering an indictment on intentional starvation, a war crime. It might be partly based on the statements of some Israeli ministers, which suggested that Israel should impose a siege on Gaza and block all supplies to it in the wake of the October 7th attack.

Israel is not a signatory to the Rome Statute, which gives the ICC its powers. The country would be unlikely to hand over its officials to stand trial. Still, the arrest warrants would “make Israel an international pariah”, says one Israeli official. It would also make it very difficult for the individuals named to engage with their foreign counterparts. They would be liable for arrest when traveling abroad to the 124 countries that recognize the ICC’s jurisdiction. Even America, which is not a signatory, would be reluctant to host them.

Simply the threat of indictment can be powerful. Israeli officials privately link recent attempts to increase aid deliveries to Gaza to the fear of ICC warrants. That is also one reason Israel delayed for weeks the next phase of its ground attacks against the remaining Hamas stronghold in the city of Rafah. Still, on May 7th Israeli forces said they had taken control of the Rafah border crossing, a crucial route for aid into Gaza, as they continue the offensive.

Some of Israel’s supporters argue that an international court’s intervention is unwarranted because the country has its own independent judiciary to hold the government to account. A petition from five human-rights organizations is currently being heard in Israel’s high court, demanding that the government do more to allow supplies into Gaza. On May 3rd petitioners argued that the government was not fulfilling the aid commitments that it made in a previous hearing. If the government cannot abide by what it says in an Israeli court, its leaders may find themselves soon having to answer an international one.

The Economist

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.