It took almost a week for Lebanon’s caretaker cabinet to convene to discuss the news that the country’s central bank governor had become a wanted man.

Rather than agreeing on decisive action after French and German courts issued arrest warrants for Riad Salameh late last month, ministers bickered over technicalities and played down the severity of the situation, according to two people with knowledge of the discussions. Few sought Salameh’s resignation, while others defended him despite the allegations that he has committed financial crimes, the people said.

“It’s shocking,” said deputy prime minister Saade Chami, one of the few senior politicians to publicly call for Salameh to quit, who spoke to the FT in the days following the cabinet meeting. “It’s not acceptable in any country for the governor of the central bank to be accused of such serious crimes and remain in his position.”

The foot-dragging is emblematic of the chronic political dysfunction that has afflicted Lebanon for years and left it mired in an unprecedented economic collapse and leadership vacuum. The country still has no government a year after national elections, with only a caretaker administration in place, and has been without a president for seven months. Leaving a man accused of corruption, money laundering and embezzlement in charge of monetary policy has pushed Lebanon’s credibility to a new low, officials and analysts said.

“It’s better for him to resign or at least step aside until the end of his term,” said Chami. “The government cannot carry on with business as usual. Something must be done to maintain whatever remaining credibility we have in the eyes of the world.”

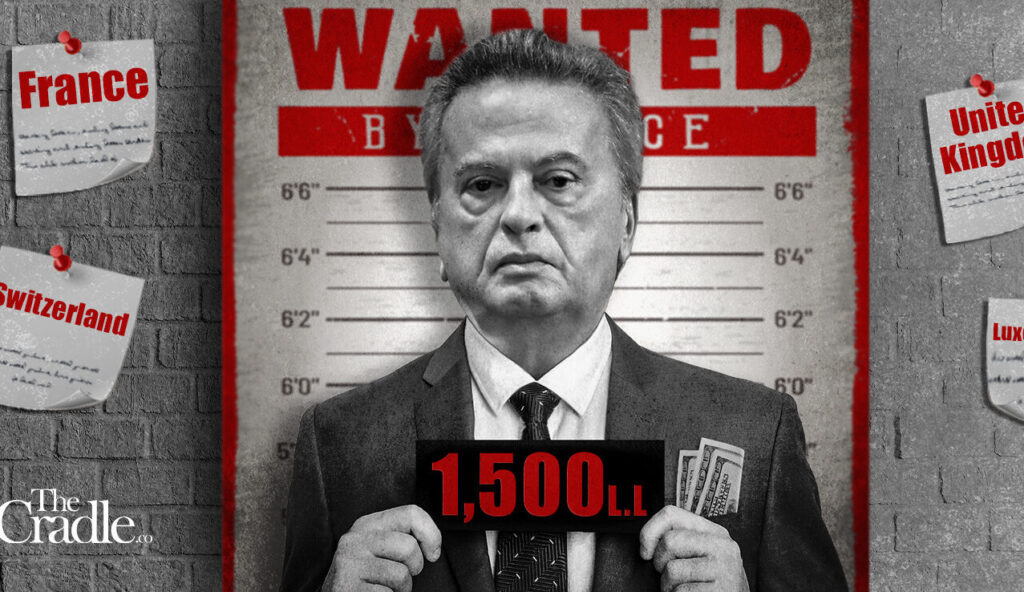

Salameh, whose picture now graces Interpol’s website, has denied any wrongdoing. The Banque du Liban governor has said he would only step down if he was convicted in court and has lambasted the “unfair” investigations against him at home and abroad.

French prosecutors and an investigating magistrate have been probing allegations that Salameh, along with his brother and an associate, illicitly enriched themselves and laundered hundreds of millions of dollars of public funds for personal gain. Salameh is also under investigation in Lebanon and at least four other European countries for alleged financial crimes.

His term is up at the end of July and, after three decades in the post, the 72-year-old has said he would not seek another. The BdL governor was once hailed as a financial mastermind who steadied Lebanon’s precarious finances through years of instability.

He has retained the support of many in Lebanon’s powerful political elite despite being widely blamed for the country’s devastating 2019 financial collapse, which has thrust three-quarters of the population into poverty.

Analysts and political insiders suggest this is because Salameh knows the secrets of Lebanon’s political class. The Lebanese pound has lost more than 98 per cent of its value against the dollar since 2019, while annual inflation climbed to 269 per cent in April.

Finance minister Youssef Khalil, who has publicly backed Salameh, and justice minister Henry Khoury have been deputed to assess the implications of the arrest warrants for state affairs. But with no further cabinet meetings scheduled and no political unanimity, Chami said the ministers’ work “won’t change a thing”.

Lebanon has a history of not extraditing its citizens and Salameh is not expected to be sent to France. Other options include forcing his resignation or letting him finish his term.

“I’m not seeing any sense of urgency,” said a senior politician in Beirut. “Instead of trying to sort out this mess, the various parties are bartering over . . . suggested replacements.”

There is no consensus on a successor, with political parties arguing about whether the caretaker government even has the power to appoint one, according to members of the administration.

One candidate, former labour minister Camille Abousleiman, has recently emerged as the favourite to replace Salameh. But negotiations have stalled amid the factionalism and horse-trading that have long dogged Lebanese politics.

Salameh’s succession is tied to the negotiations for the choice of president, which is nowhere near resolution, political insiders and analysts said

Under Lebanon’s confessional political system, the presidency is reserved for a Maronite Christian. Suleiman Franjieh, a friend of Syria’s leader Bashar al-Assad, is favoured by Hizbollah, the Iran-backed Shia political party and militant group that wields significant influence in Lebanon, and its ally Amal. Together, they hold an effective veto on cabinet appointments.

However, Franjieh lacks broad support among Lebanon’s Christians and despite intense lobbying from longtime Lebanese ally France, he has yet to clinch the nomination.

In a challenge to Franjieh’s nomination, Lebanon’s main Christian parties and a group of independent MPs on Sunday nominated Jihad Azour, an IMF official and former finance minister, as their candidate for president.

“France’s support for Franjieh is first and foremost about expediency,” with some in Paris believing his proximity to Assad could be useful, said Rym Momtaz, consultant research fellow at the IISS think-tank and an expert on French foreign policy. “It’s unwilling to challenge Hizbollah and Amal so, under the guise of avoiding a long institutional void at the presidency . . . it has accepted their terms.”

Sami Atallah, founding director of The Policy Initiative think-tank in Beirut, said the warrants against Salameh were a shock for Lebanon’s political leaders, “[in whose] imagination accountability doesn’t figure.”

But “instead of motivating them to clean up their act, they’re doubling down by keeping Salameh in place and launching attacks on journalists and the judiciary,” he said.

The political vacuum suited them as it left no path for reforms that could erode their power, he added, citing the lack of progress on economic and political measures demanded by the IMF to unlock investment and aid.

Lebanon’s citizens are bearing the brunt of the impasse. “These political leaders and this government have no shame,” said Marie, who did not want her surname published because she was embarrassed at how low she had fallen. “I used to be a teacher,” she said. “Now, I’m begging for my children’s breakfast . . . while [Lebanon’s leaders] sit in their golden palaces.”

FINANCIAL TIMES

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.