Pro Hezbollah media in Lebanon credited a phone call made by Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah to Iraqi Shiite cleric and politician Muqtada Al-Sadr for halting Iraq’s slide back into war, but Iraqi officials and insiders insist it was only grand ayatollah Sistani’s stance behind the scenes that that halted the meltdown

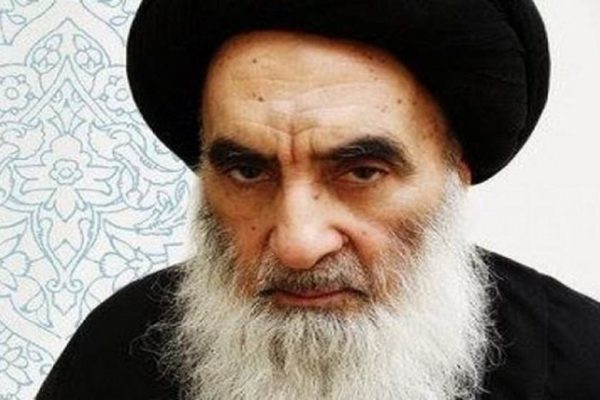

BAGHDAD- When a pronouncement by a religious scholar in Iran drove Iraq to the brink of civil war last week, there was only one man who could stop it: A 92-year-old Iraqi Shiite cleric who proved once again he is the most powerful man in his country.

Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Sistani said nothing in public about the unrest that erupted on Iraq’s streets. But government officials and Shiite insiders say it was only Al-Sistani’s stance behind the scenes that halted a meltdown.

The story of Iraq’s bloodiest week in nearly three years shows the limits of traditional politics in a country where the power to start and stop wars rests with clerics — many with ambiguous ties to Iran, the Shiite theocracy next door.

The Iraqis who took to the streets blamed Tehran for whipping up the violence, which began after a cleric based in Iran denounced Iraq’s most popular politician, Moqtada Al-Sadr, and instructed his own followers — including Al-Sadr himself — to seek guidance from Iran’s Supreme Leader.

Al-Sadr’s followers tried to storm government buildings. By nightfall they were driving through Baghdad in pickup trucks brandishing machine guns and bazookas.

Armed men believed to be members of pro-Iranian militia opened fire on Sadrist demonstrators who threw stones. At least 30 people were killed.

And then, within 24 hours, it was over as suddenly as it started. Al-Sadr returned to the airwaves and called for calm. His armed supporters and unarmed followers began leaving the streets, the army lifted an overnight curfew and a fragile calm descended upon the capital.

To understand both how the unrest broke out and how it was quelled, Reuters spoke with nearly 20 officials from the Iraqi government, Al-Sadr’s movement and rival Shiite factions seen as pro-Iranian. Most spoke on condition of anonymity.

Those interviews all pointed to a decisive intervention behind the scenes by Al-Sistani, who has never held formal political office in Iraq but presides as the most influential scholar in its Shiite religious center, Najaf.

Officials said Al-Sistani’s office ensured Al-Sadr understood that unless Al-Sadr called off the violence by his followers, Al-Sistani would denounce the unrest.

“Al-Sistani sent a message to Al-Sadr, that if he did not stop the violence then Al-Sistani would be forced to release a statement calling for a stopping of fighting — this would have made Al-Sadr look weak, and as if he’d caused bloodshed in Iraq,” said an Iraqi government official.

Three Shiite figures based in Najaf and close to Al-Sistani would not confirm that Al-Sistani’s office sent an explicit message to Al-Sadr. But they said it would have been clear to Al-Sadr that Al-Sistani would soon speak out unless Al-Sadr called off the unrest.

An Iran-aligned official in the region said that if it were not for Al-Sistani’s office, “Moqtada Al-Sadr would not have held his press conference” that halted the fighting.

Al-Sistani’s intervention may have averted wider bloodshed for now. But it does not solve the problem of maintaining calm in a country where so much power resides outside the political system in the Shiite clergy, including among clerics with intimate ties to Iran.

Al-Sistani, who has intervened decisively at crucial moments in Iraq’s history since the US invasion that toppled Saddam Hussein, has no obvious successor. Despite his age, little is known publicly about the state of his health.

Those interviews all pointed to a decisive intervention behind the scenes by Al-Sistani, who has never held formal political office in Iraq but presides as the most influential scholar in its Shiite religious center, Najaf.

Officials said Al-Sistani’s office ensured Al-Sadr understood that unless Al-Sadr called off the violence by his followers, Al-Sistani would denounce the unrest.

“Al-Sistani sent a message to Al-Sadr, that if he did not stop the violence then Al-Sistani would be forced to release a statement calling for a stopping of fighting — this would have made Al-Sadr look weak, and as if he’d caused bloodshed in Iraq,” said an Iraqi government official.

Three Shiite figures based in Najaf and close to Al-Sistani would not confirm that Al-Sistani’s office sent an explicit message to Al-Sadr. But they said it would have been clear to Al-Sadr that Al-Sistani would soon speak out unless Al-Sadr called off the unrest.

An Iran-aligned official in the region said that if it were not for Al-Sistani’s office, “Moqtada Al-Sadr would not have held his press conference” that halted the fighting.

Al-Sistani’s intervention may have averted wider bloodshed for now. But it does not solve the problem of maintaining calm in a country where so much power resides outside the political system in the Shiite clergy, including among clerics with intimate ties to Iran.

Al-Sistani, who has intervened decisively at crucial moments in Iraq’s history since the US invasion that toppled Saddam Hussein, has no obvious successor. Despite his age, little is known publicly about the state of his health.

Meanwhile, many of the most influential Shiite figures — including Al-Sadr himself at various points in his career — have studied, lived and worked in Iran, a theocracy which makes no attempt to separate clerical influence from state power.

Last week’s violence began after Ayatollah Kadhim Al-Haeri, a top ranking Iraqi-born Shiite cleric who has lived in Iran for decades, announced he was retiring from public life and shutting down his office due to advanced age. Such a move is practically unknown in the 1,300-year history of Shiite Islam, where top clerics are typically revered until death.

Al-Haeri had been anointed as Al-Sadr’s movement’s spiritual adviser by Al-Sadr’s father, himself a revered cleric who was assassinated by Saddam’s regime in 1999.

In announcing his own resignation, Haeri denounced Al-Sadr for causing rifts among Shiites, and called on his own followers to seek future guidance on religious matters from Ayatollah Ali Khamenei — the cleric who also happens to rule the Iranian state.

Arab News/ Reuters

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.