BY SAM MCMANUS

Lebanon isn’t only the pictures we see in the news. The scene that comes to my mind is one from the spring of 2019. I’m standing at the viewpoint of Saydet el Nourieh shrine, in Hamat, high on a cliff, looking out across the landscape. The turquoise breakers of the eastern Mediterranean meet the coast at the city of Tripoli, after which the land rises through foothills dusted with snow to brooding mountain peaks wrapped in a heavy coat of white. The scene has some of the familiarity of Southern Europe. The traditional houses are made of a solid, creamy stone, topped with orange roof tiles. The woodlands comprise windswept green poplars and Grecian trees with branches like smoke tendrils. Yet all the road signs are in Arabic and the unmistakeable dust of the Middle East hangs in the air.

Lebanon is the perfect balance between two worlds, the apex of the meeting point between East and the West, which accounts for both its compelling history and cultural richness — and its turbulence. The first time I went to Lebanon I was supposed to stay for a week but ended up staying for a month.

I was researching whether — and how — to a launch a guided tour in the country. At the time, only a handful of British companies were offering itineraries in Lebanon but its revised and improved safety credentials in the eyes of the British Government Foreign & Commonwealth Office meant there’d soon be more of an appetite. So I took a tiny apartment in Beirut on the top floor of a five-story block with an open terrace, views of the sea and a malicious landlady, and began my research. My time in Lebanon was intoxicating. In November 2019, I’d be back again, leading YellowWood Adventures’ first group of clients around the country (and staying on again for a further three weeks, purportedly to observe the pro-democracy protests, but really just because it was nice to be there).

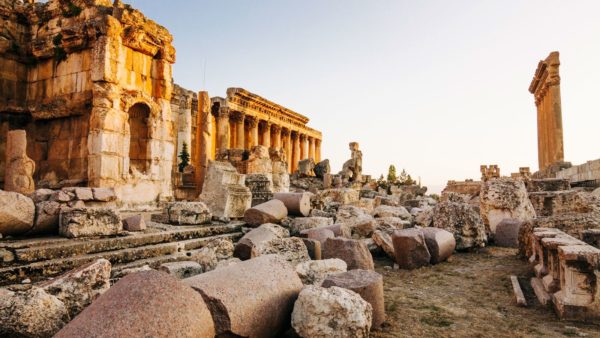

Lebanon is a tiny strip of a country bordered to the south by Israel, with two spines of mountains running perpendicular north to south: the Mount Lebanon range overlooking Beirut and the coast, and the Anti-Lebanon range further east forming a natural border to Syria. Lying between the two, the lush Beqaa Valley houses vineyards and grand chateaus, and feels like France. Here, I explored grand Roman ruins (some of the most significant outside of Italy) of the Temple of Bacchus and Temple of Jupiter in Baalbek. To the Greeks and Romans, this was the bustling ceremonial centre of Heliopolis, their ‘City of the Sun’, but the streets were quiet. Only the smells of manakish (hot breads served with cheese or zaatar) filled the morning air.

Elsewhere on my trip, my Lebanese friend Milead took me snowshoeing among the cedar forests that crown the head of the Qadisha Valley, which has sheltered Christian communities since the religion began. ‘Qadisha’ means ‘holy’ in Aramaic. And in Byblos, one of the oldest continuously inhabited towns on Earth, and originally home to the seafaring Phoenicians, we ate olives at the legendary Pepe’s Fishing Club restaurant, overlooking the port. The menu informed me, somewhat unnecessarily, that the now-deceased proprietor was ‘a renowned ladies’ man’.

I found Beirut to be both glamorous and high-maintenance. In the centre of the city, a beautiful mosque encircled by four minarets stands beside a church with a single tower supporting a crucifix constructed from bright, square lights. Some of the bulbs have blown and the effect always reminded me of the lurid, romantic aesthetic of Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film Romeo + Juliet. At nightfall, the lights from the city give a wondrous shimmering haze to the air, like a finely woven fabric.

Which brings me to the present day. On the 4 August 2020, the eyes of the world were on the Lebanese capital as a terrible blast — caused by 2,700 tonnes of inadequately stored ammonium nitrate — ripped through its port. The damage to the city is estimated at $10 to 15 billion , and around 300,000 people were made homeless. In total, at least 190 people lost their lives. It was a blow upon a bruise for Lebanon, already in steady economic decline caused by a corrupt political system built in the wake of the 1975-1990 Lebanese Civil War. In early 2019, protests against the government brought many local economies to a further standstill. Then came the coronavirus pandemic. Then the blast.

But Lebanon is again rebuilding itself.

Maya Terro, who runs YellowWood Adventures’ partner charity, FoodBlessed, is providing thousands of food parcels to those who need it most. In this melting-pot city, there’s a rich tapestry of beliefs and communities, but aid is meted out regardless of race, religion, nationality or sex. “We call our beneficiaries ‘guests’,” Maya says, explaining the intersection of dignity and compassion in their charity. “Now many of the middle class have now become poor, and the poor destitute.”

In the weeks following the blast, I also heard from our business partner, Johanna Nader, from Lebanese tourism company TLB Destinations. She’s temporarily put aside tourism and switched to mapping the areas of Beirut that most need help, so nowhere gets overlooked. But, she assures me, she’s keen to return to her job as soon as possible. “The only industry left in Lebanon is tourism,” she says. “The salaries of the janitor in a restaurant to the musician in a pub to the owner of an hotel rely solely on tourism, which helps to bring in foreign currency directly — our local currency has no value anymore.” She added: “The Lebanese also need tourism to fall in love all over again with their own country.”

I aim to play my part by returning to visit as soon as flights resume and the British government deems it safe, and hope more travellers will join me in 2021 on YellowWood Adventures’ tours.

Until then, when I think of Lebanon, I won’t remember only the shocking images of the recent blast or scenes from the protests. I’ll think of the sea and the mountains, and my friends.

“Lots of countries offer clean roads, streets, a bit of history, but Lebanon offers real soul. It’s the people all over the country that make this place quite unique,” my friend Rana Jabre, a piano teacher in Beirut, told me recently. She’s already restored 22 apartments in the city with windows and furniture, with only the help of a friend and carpenter, entirely funded from donations via Facebook. “You know, the cedar trees of Lebanon are mentioned 103 times in the Bible,” she said. “They represent resilience and strength because they still flourish in tough conditions. We Lebanese are like the cedar trees.”

The National Geographic

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.