Lebanon is transfixed by reports that Prime Minister Saad Hariri gave $16 million to a South African model with whom he was romantically linked. The money transfers began in 2013, when Hariri was not in office, and no laws appear to have been broken. For some, it is a welcome diversion from a deepening economic crisis, for others, a reminder of the yawning gap between Lebanese, who are struggling with a serious currency crunch, and their leaders.

But neither the state of the economy nor the louche behavior of prominent politicians can long distract Lebanese from their greatest fear—of their country becoming a battleground in the geopolitical contest pitting Iran against the U.S. and Saudi Arabia.

In a country scarred by too many proxy battles, there’s a persistent nightmare of being dragged into an armed conflict in which most Lebanese have no stake. Short of that, there is a real risk of being regarded as little more than a Hezbollah front state—by both sides. That would mean being treated as a kind of colony by the Islamic Republic, and being ostracized and sanctioned by much of the Arab world and the West.

The first gambit in the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran was a concentrated salvo of new sanctions against Hezbollah that intensified throughout 2017 and 2018. Marshall Billingslea, the Treasury’s assistant secretary for terrorist financing, led the push to isolate Hezbollah and convince Lebanese bankers and state institutions to stop doing business with the pro-Iranian group. In August, the US sanctioned the Jammal Trust Bank in August for facilitating banking for Hezbollah; the Lebanese central bank has since allowed it to be liquidated.

As Billingslea and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo have acknowledged, many of the Lebanese they engaged have tried to cooperate. But Hezbollah has a wide range of options, in both the formal and informal sectors. The group also has substantial public support, especially among Shiites and Christians, which gives it an important role in parliament, and in any governing coalition.

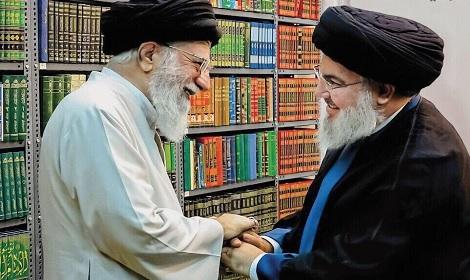

Most important, it has a powerful, well-armed militia. Having been blooded but also honed in numerous conflicts with Israel, its military capabilities have recently been greatly refined in the Syrian war, where it is heavily engaged on the side of the Assad regime. As a result, Hezbollah’s military has evolved into, arguably the world’s most potent non-state armed force.

This makes Hezbollah an important sanctions target for the U.S.: it is no longer merely a Lebanese militia and political party but a regional factor, a transnational revolutionary vanguard that trains, supplies and directs pro-Iranian groups throughout the Arab world, from Syria to Yemen. And there is the constant threat of another war between Israel and Hezbollah, with both sides issuing dire threats.

Hezbollah’s military power and belligerent rhetoric makes it almost impossible for the other Lebanese to restrain the group. Frustrated, some in Washington and the Gulf Arab capitals are inclined to throw their hands up and simply brand all of Lebanon as a de-facto terrorist entity. That would mean defunding or sanctioning virtually anything connected to the Lebanese state.

Tony Badran and Jonathan Schanzer of the influential Foundation for the Defense of Democracies think tank recently argued it was “acknowledge Lebanon as the Hezbollah state, and act accordingly.” The authors are openly expressing an agenda that is quietly gaining ground in the US, Israel and Gulf Arab countries in the context of the confrontation with Iran and its network of regional proxies.

But this approach would be deeply unfair. After all, the countries that are now conflating all of Lebanon with Hezbollah played important roles in enabling the militia’s rise. The 1989 Taif Agreement which ended the 15-year civil war was essentially an Iranian-Saudi accommodation brokered by the U.S. In effect, it disarmed all armed groups except Hezbollah. The 1996 Israeli–Lebanese Ceasefire Understanding, also brokered by Washington, left Hezbollah in a dominant national position. Hariri is right when he protests that it’s not his fault Hezbollah has become so powerful.

Besides, abandoning Lebanon now to Hezbollah domination would effectively cede control of the country to Iran. There’s a real risk Lebanon could return to the state of violent anarchy that characterized its civil wars, or lapse into a failed state. In any of those eventualities, it would represent a much greater threat to the region than Hezbollah does now.

It makes much more sense for the U.S. and other Arab states to redouble support for those parts of Lebanon—and in particular, civil society and political groups—that oppose Hezbollah and urgently need strengthening. Lebanon also deserves help in dealing with the 1 million Syrian refugees (compared to its native population of 4 million) it has absorbed, effectively on behalf of the rest of the world.

Lebanon is not a Hezbollah state, but treating it like one risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

BLOOMBERG

By

By

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.