By Karoun Demirjian

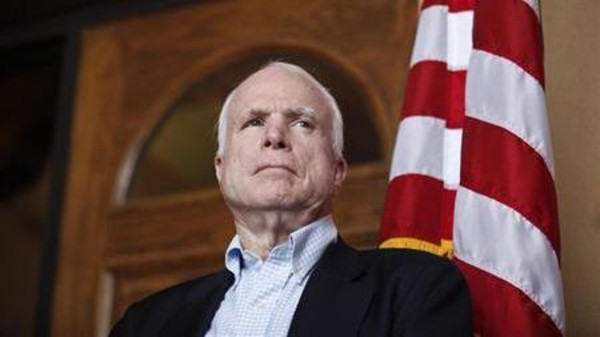

Sen. John McCain’s death heralds a sea change for congressional challenges to the Trump administration on national security, as the president’s two most vocal Republican critics pass their powerful committee gavels to two of President Trump’s biggest supporters.

McCain (R-Ariz.), who used his chairmanship of the Senate Armed Services Committee to question the president’s stance on issues such as Russia, torture and immigration, leaves control to Sen. James M. Inhofe (R-Okla.). Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker (R-Tenn.), who has been a one-man Greek chorus of epithets decrying Trump’s chaotic approach to diplomacy, will hand the reins to Sen. James E. Risch (R-Idaho) at the start of the new year.

The departure of either committee chairman would be noteworthy, as both have attracted considerable attention for criticizing the White House over foreign policies they deem flawed. But together, they portend a sweeping change in how Congress may use its oversight authority to check the president’s international agenda, according to current and former lawmakers, lobbyists and policy watchers — a changing of the guard with potentially enormous consequences for holding the president to account during crises.

“Corker and McCain, the way they have led those committees, have been exceptions to the rule. . . . Both have done a good job of really probing and questioning and disagreeing with their own Republican president when they needed to,” said former defense secretary Chuck Hagel, who also served in the Senate as a Republican alongside McCain, Corker, Inhofe and Risch. “That will shift — there’s no question about it.”

McCain and Corker have been celebrated for the tenacity they have brought to oversight of both Democratic and Republican administrations. As a former presidential candidate, Vietnam War hero and one of the most recognizable American statesmen on the world stage, McCain was one of the few lawmakers who could often command more authority on national security than the commander in chief — which he used to dare presidents to cross him.

Since Trump took office, that has happened most frequently on matters concerning Russia.

McCain and Corker have been as pointed in their criticism of Trump’s actions vis-a-vis Russian President Vladimir Putin as they were instrumental last year in getting Congress to pass sanctions that checked the president’s authority to scale back punitive measures against Moscow without lawmakers’ approval.

Both also led repeated legislative efforts to reaffirm the United States’ commitment to NATO in the face of presidential statements they thought were intentionally designed to undermine it.

“No prior president has ever abased himself more abjectly before a tyrant,” McCain said of Trump’s performance during a July summit in Helsinki, in which the U.S. president suggested he might take Putin’s denials of interference in the 2016 election over the findings of his own intelligence community.

“The Helsinki conference was a sad day for our country, and everyone knows it,” Corker said, calling Trump’s performance “deplorable.”

Such commentary earned them the jeers of the president and his allies but the cheers of the foreign policy establishment — and the previous administration.

“I don’t like to picture a Senate without Bob Corker and John McCain . . . sometimes we butted heads hard, but I never doubted for a second that they were serious,” former secretary of state John F. Kerry said in an email.

McCain and Corker both grilled Kerry fiercely over the Obama administration’s policies, including the deal with Iran to end crippling sanctions in exchange for curbs on its nuclear program.

Both lawmakers opposed the deal, though Corker, who led the legislative effort to guarantee that Congress could review the pact, later urged Trump not to withdraw from it.

“You need enough people like that on both sides to create a critical mass to get something done, otherwise you have a big flashing disincentive that empowers the worst actors to call the shots,” Kerry said.

Colleagues fear the Senate will lose that edge once Inhofe and Risch take over, concerned that they will be more acquiescent to the White House.

“We’ve transferred a lot of authority to the executive over the years . . . and I’m concerned that new leadership that is closer to the president doesn’t view as skeptically as it should executive power,” said Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.), who has also criticized Trump’s approach to foreign policy and is also retiring at the end of his term. “I think they’re less likely to question moves by the president . . . it’s going to be less independent.”

McCain’s death comes at a critical juncture, as the Trump administration slaps steep, controversial tariffs on adversary and allied nations and attempts, in fits and starts, to strike a historic denuclearization agreement with North Korea — one that has eluded previous administrations for decades.

Democrats and Republicans alike have railed against the tariffs and expressed skepticism about the likelihood of talks between Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un succeeding. They have challenged Trump’s team to articulate a clearer strategy to hold Pyongyang to account — not only for its nuclear arsenal, but the aggression and threats it carries out in cyberspace, via biological and chemical weapons, and against the human rights of its own people.

But from their perch on their respective panels, Inhofe and Risch have chided those who voice doubts about the president’s ability to orchestrate a historic denuclearization deal — even when that person is the president’s own director of national intelligence.

“I’m a little more optimistic than your ‘hope springs eternal,’ Dan, and I want to think that this aggressive behavior of our president is going to have a positive effect on [Kim],” Inhofe said to Director of National Intelligence Daniel Coats this year during a Senate Armed Services Committee, after Coats expressed skepticism that the North Korean leader would ever give up his nuclear weapons.

More recently, Risch effectively admonished lawmakers who have expressed concern that Trump might overlook Kim’s human rights record to strike a deal, urging them to trust the president.

“Look, we’re all about human rights . . . but if you try to overload this and try to resolve all these things at once, I think you’re just setting things up for failure,” Risch said during a Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee hearing on North Korea in June. “We have a different situation with President Trump than we have in the past . . . Kim Jong Un recognizes that he’s dealing with a person who has a very strong personality, and he’s not going to tolerate the kinds of things that have happened in the past.”

In general, both Risch and Inhofe have approached the business of executive oversight with less zeal than either McCain or Corker. Risch, who chairs the Senate Foreign Relations panel’s subcommittee on the Near East, South Asia, Central Asia and counterterrorism — a portfolio that also gives him jurisdiction over Afghanistan and Pakistan — has not held a single subcommittee hearing since Trump took office.

By comparison, Inhofe is far more active. He took the reins of the Armed Services Committee as McCain remained in Arizona since December, undergoing treatment for brain cancer. Inhofe has worked with McCain’s staff through the summer to steer a record-setting $716 billion measure outlining defense priorities through Congress. But even that bill — named after McCain this year, though Trump did not mention his name at the signing — bears marks of the late senator that experts think Inhofe will be hard-pressed to replicate.

For years, McCain waged a battle against the Defense Department to reduce excessive spending on costly programs, such as the F-35 fighter jet and the Ford class aircraft carrier. He was credited with driving an investigation that exposed the George W. Bush administration’s Air Force tanker lease deal that seemingly shortchanged Boeing, a recent defense spending scandal. Lobbyists have also long eyed Inhofe as more deferential to the department and sympathetic to the contracting industry than McCain.

But McCain has also been one of the chief champions of increasing military spending, taking on Trump last year.

“What he did was remarkable: The president of his own party put forth a budget, and he put forth an alternate budget and strategy saying, ‘My own party is underfunding the Department of Defense,’ ” said Mackenzie Eaglen, a defense expert with the American Enterprise Institute. “[McCain] went farther than [Defense Secretary] Jim Mattis had gone. And he won . . . I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) eventually deferred to McCain over Trump, and the bill secured veto-proof majorities in Congress. It was the second time in a year that a McCain-backed bill had successfully forced Trump to sign a foreign or defense policy he had pushed against — the first being the legislation that gave Congress the power to block conciliatory moves on Russia sanctions.

Since McCain’s diagnosis, his faceoffs with Trump were largely restricted to official statements and through Twitter, where the senator made a point of reserving carefully worded vitriol for the matters that most defined him. On the matter of torture, he challenged lawmakers to vote against confirming now-CIA Director Gina Haspel, who was involved in the agency’s interrogation program. On the rule of law and matters concerning allegations of Russian interference, he reprimanded Trump for attacking special counsel Robert S. Mueller III and his probe. And in response to Trump’s statements flouting long-standing global alliances, he has gone around the president to address other nations on behalf of the American people.

“Americans stand with you, even if our president doesn’t,” he wrote on Twitter after Trump’s break with the Group of Seven.

McCain hasn’t been entirely alone in the GOP in his criticism. Flake and Sen. Rand Paul (Ky.) joined him in opposing Haspel, while several Senate Republicans similarly excoriated the president over his deference to Putin in Helsinki, admonished the president for attacking Mueller, and blasted him for disregarding the United States’ oldest allies.

But lawmakers openly wonder whether, in the era of Trump, there is anyone in Congress who can fill the void McCain and Corker will leave.

Sen. Christopher A. Coons (D-Del.) ticks off the names of five Republican senators who could step up — Sens. Marco Rubio (Fla.), Todd C. Young (Ind.), Cory Gardner (Colo.), Ben Sasse (Neb.) and Thom Tillis (N.C.).

“These are all folks who have shown some independence and taken some initiative. You don’t leap from being a first-term senator to being a John McCain, but there is an opening,” said Coons, a close friend of McCain’s.

“I think it is a tragedy Senator Corker served only two terms. I think he had a great deal more to give us,” Coons said. “And it’s an equal but greater tragedy that Senator McCain will not be with us for another decade. We need both heroes and fighters, and McCain and Corker are both.”

Karoun Demirjian is a congressional reporter covering national security, including defense, foreign policy, intelligence and matters concerning the judiciary. She was previously a correspondent based in The Post’s bureau in Moscow.

THE WASHINGTON POST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.