Proposed amendment will see Lebanese women finally able to pass citizenship to their children – but not if they marry a Palestinian or Syrian

A Lebanese official is proposing legislation that would finally give women in the country the right to pass down citizenship to their children – but with an exception that activists say defeats the purpose of the reform.

On 21 March – Mother’s Day in Lebanon and a little more than a month before the country’s first parliamentary election in nine years – Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil announced he would submit an amendment to the country’s nationality law that would give Lebanese women married to foreign men the right to transfer their nationality to their children.

The initiative “applies the principle of equality between all Lebanese women and men”, Bassil said.

But there is one significant exception in the minister’s proposal: the right would not extend to Lebanese women married to citizens of “neighbouring countries”, meaning Syrians or Palestinians. Bassil said he would also seek to remove the right of Lebanese men to confer citizenship to their Syrian or Palestinian wives and the children of those marriages.

Lebanon is one of 26 countries in the world that do not give women equal rights to men when it comes to passing on their nationality to their children, according to a 2017 report by the United Nations refugee agency.

Regional reforms

Most of those countries are in the Middle East and North Africa, but in recent years some countries in the region have reformed their nationality laws, including Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen.

Lebanese men can confer their citizenship to their wives and children. Lebanese women, on the other hand, can only pass down their citizenship is if the child is born out of wedlock, something that is heavily stigmatised in Lebanese society.

Those raised in Lebanon without citizenship face a range of problems in accessing education, healthcare and work.

For nearly two decades, activists have been campaigning to change the law, which dates to a French Mandate-era law, created in 1925, but so far without success.

Amal Bourji is Lebanese and her husband has Syrian nationality – although his mother was also Lebanese and he was raised in Lebanon. Their two young daughters therefore do not have Lebanese nationality.

The family struggles to make ends meet – as a Syrian, Bourji’s husband can only work informally without a regular hourly salary or insurance. He works 12 or 15 hour days as a delivery man so the couple can pay the $450 rent on their house and other expenses, including $2,000 a year for school for their elder daughter.

“The decision is unacceptable,” Bourji said of Bassil’s proposal. “They need to give the right to everyone.”

‘Preventing settlement’

Bassil said when presenting the bill that the proposed exception was aimed at preventing “settlement” by the Syrians and Palestinians and noted that his proposal would allow granting of citizenship for those groups on a case-by-case basis.

“The Lebanese state is committed to the right of return for Palestinian refugees and displaced Syrians, so we have to take into account the consequences of granting citizenship,” he said.

Lebanon is home to about 174,000 Palestinian refugees, according to a census released last year. They are not eligible for citizenship although most of them at this point were born and raised in the country.

The civil war in Syria brought another mass of refugees across the border, and there are now more than one million Syrians living in the country, which has a total population of about six million, according to the World Bank.

The presence of both groups has raised concerns, especially among Christians and Shia Muslims, as most of the Palestinians and Syrians are Sunni. Bassil is a Maronite Christian.

The groups that have been campaigning for reforms to the nationality law are now campaigning against Bassil’s proposal, calling it discriminatory.

The Lebanese Council of Women and My Nationality is a Right for Me and My Family Campaign issued a joint statement calling Bassil’s proposal a “deceitful bill that deprives Lebanese women and their families from their legitimate rights”.

Human Rights Watch has called the proposed reform “discriminatory and fatally flawed”.

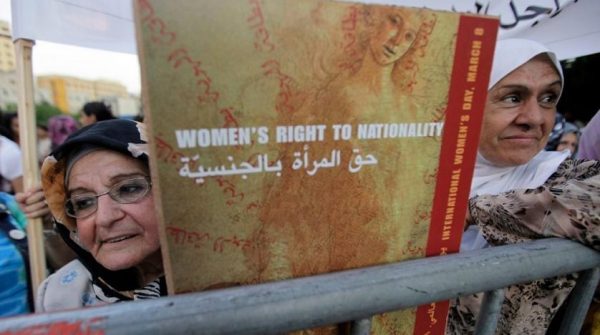

Families affected by the nationality law staged a protest on Easter Sunday, organised by the group Jinsiyati Karamati or My Nationality, My Dignity campaign.

The several hundred people assembled in downtown Beirut chanted “We want nationality for the Lebanese mothers, enough racism” and “I am Lebanese – I want nationality without exception”.

A stranger in one’s own country

Even some of those who would potentially benefit from the law have qualms with the exception.

Inas Assaf is married to a Zimbabwean man whom she met while he was working for the United Nations in Lebanon on a landmine-clearing project.

Their six-year-old son, Adam, has lived his whole life in Lebanon. He travelled with Assaf to Zimbabwe for the first time in October, on a mission to renew his passport, which was about to expire.

Upon their return to Beirut, Assaf was infuriated when the passport control agents insisted that she pay a visa fee for her son as if he were a foreigner.

“Suddenly, just like that, my son is a stranger in his country,” she said.

Due to backlogs in the system, Adam’s new passport still has not been issued, meaning that she has been unable to renew his Lebanese residency – which he is eligible for, despite the lack of a Lebanese passport – and as a result cannot access services such as health insurance.

Although it might help her family, Assaf said she is not happy with Bassil’s proposal.

“I think it’s unfair, still,” she said. “OK, my son is Zimbabwean, but still I can put myself on the other side.”

The proposal has also met with opposition in the government, but it remains unclear if it will be enough to stop its passage.

Prime Minister Saad al Hariri, the most prominent Sunni politician in the country, told a Women Leaders Council of Lebanon meeting on Saturday: “It is very critical and basic that Lebanese women be able to give their nationality to their children… and we must get away from sectarian concerns and the sectarianism that we have in order to establish this right.”

A government source with knowledge of the matter said Hariri specifically objected to the exemption of women married to Palestinians and Syrians and that “it would be unconstitutional anyway to differentiate between a Lebanese citizen and another based on who she is married to”.

Two years ago, Bassil successfully pushed legislation to grant citizenship to descendants of Lebanese emigrants who were born and raised abroad.

Lina Abou Habib, chair of the organisation Collective for Research and Training on Development-Action, one of the leaders in the movement for reform, said although she finds Bassil’s current proposal “outrageous”, he might have the political clout to pass this one, too.

“He has pushed for such laws before,” Abou Habib said. “It wouldn’t be preposterous to think that he may push to get this law passed as well.”

MEE

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.