Chileans voted for a successor to President Michelle Bachelet on Sunday, with billionaire conservative Sebastian Pinera the favorite to win, though a crowded field of leftist challengers are likely to force a December runoff

“Pinera’s the best candidate. Plus, he already governed. We know who he is,” said Fresia Jara, a 73-year-old retiree as she left a polling station in the capital Santiago.

Former TV anchorman, Senator Alejandro Guillier, is the flagbearer for Bachelet’s fractured center-left Nueva Mayoria coalition. He leads the race for second place, with around 21 percent of likely voter support compared to about 42 percent for Pinera, according to a CEP poll last month.

The election is the latest in South America to pit left-leaning politicians against the conservatives increasingly taking their places.

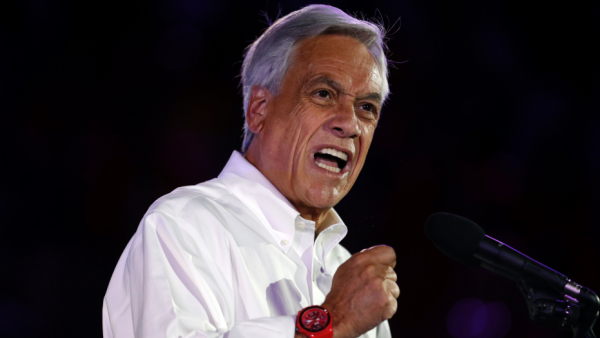

Pinera has pitched himself as a vote for a brighter future.

“Today we’re going to make a decision that will impact our lives for many decades,” Pinera told journalists after voting at a school in Santiago on Sunday. “I know we’re going to pick the right path, the one that takes us to better times.”

This year’s vote is a turning point for Chile’s coalition of center-left parties, previously known as the Concertacion. The pact, which for decades has dominated Chilean politics, fissured under Bachelet, riven by disagreements over policies such as loosening Chile’s strict abortion laws and strengthening unions.

Bachelet, who is barred from running in this election by term limits, will step down with approval ratings near 30 percent and the legacy of her social and economic policies uncertain.

Many Chileans view the election as a referendum on her second term, which focused on reducing inequality by expanding access to free education and overhauling the tax code.

Pinera, the market favorite, campaigned on a platform of scaling back and “perfecting” her tax and labor laws, seen by many in the business community as having crimped investment at a time when slumping copper prices were already driving down economic growth in the world’s No. 1 copper producer.

Guillier, who is ideologically aligned with Bachelet, has promised to deepen her reforms and has tapped support from Chileans who view Pinera as a setback for gains made for students, women and workers.

“I voted for Guillier because I think we have to continue to provide free education. It’s a social right,” said unemployed voter Mario Giannetti, 53.

Pinera garnered international attention and domestic praise for his handling of the dramatic rescue of 33 trapped miners during his prior term in 2010, and is seen as a safe pair of hands by investors.

But his administration was marred by massive student protests seeking an education overhaul. His responses were often seen as out of touch and grassroots groups still oppose him.

Both Pinera and Guillier would keep in place the longstanding free-market economic model in one of Latin America’s most developed countries.

SUBDUED ATMOSPHERE

On the eve of the vote, the atmosphere in Chilean capital Santiago was subdued. New restrictions on campaigning have left the city uncluttered with political posters and the sense that a Pinera victory was inevitable had quieted the usual political debates in cafes and bars.

In addition, Chileans have grown disenchanted with politics following campaign financing and other cash-for-influence scandals that have entangled politicians on both the left and right.

Voter turnout will serve as a bellwether for the runoff.

A strong showing of voters could help the left marshal enough votes to defeat Pinera in the second round, while apathy and continued quarrelling among left-leaning parties would pave the way for a Pinera victory.

Bachelet’s administration offered free rides to voting centers on public transportation, part of a get-out-the-vote campaign criticized by Pinera’s campaign as a political maneuver aimed at bolstering Guillier.

“It’s important for people to turn out, to exercise their right as a citizen and vote for whoever they think represents what they want for Chile,” Bachelet told journalists Sunday.

Turnout in elections following Chile’s transition from compulsory to voluntary voting in 2012 has dipped as low as 42 percent, near the bottom of developed countries, according to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

“I‘m not going to vote because in the end it doesn’t change anything,” said Santiago resident Catalina Avedano, 38, as she waited in line at a public health center this week.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.