Many Hezbollah fighters believe their Iranian supervisor in Syria views them as easily replaceable Arab cannon fodder, and the resultant tension is generating disillusionment about Tehran’s claims of pan-Shiite unity.

The deteriorating relations between Hezbollah and Syrian regime fighters are no longer secret. Lebanese social media platforms affiliated with Shiite supporters of Hezbollah are replete with mockery of the Syrian army’s incompetence, corruption, clumsiness, cowardice, and lack of resources. Bashar al-Assad’s forces are often blamed for causing Hezbollah losses or hampering operations against the rebels. While this trend has seemingly inflated egos among the group’s core supporters back home, it also suggests that political and military alliances are more complicated on the ground in Syria.

Relations between Hezbollah fighters and their commanders in Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) are similarly complicated, but much more problematic to discuss publicly. Hezbollah remains Iran’s most skilled militia, but anecdotal accounts indicate that it may no longer enjoy its privileged status with Tehran, at least in terms of how its forces are treated on the battlefield. The war in Syria has uncovered Iran’s true expansionist intentions, along with a Persian arrogance toward Arab Shiites that Hezbollah fighters are not used to.

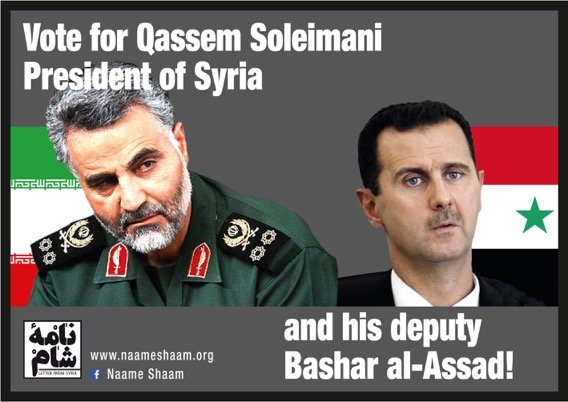

To get a better sense of how the group’s members perceive these dynamics, this article draws on author interviews with a large number of Hezbollah fighters and commanders. Although there is no way to tell how representative their views are, the high level of agreement they express on certain issues is telling. In particular, they tend to blame IRGC-Qods Force commander Qasem Soleimani for the deteriorating relations.

THE SOLEIMANI EFFECT

After Soleimani was dispatched to Syria in the early days of the war, the Hezbollah-Iran dynamic changed quickly. The group’s commanders had already been working under the IRGC’s supervision for years, but Soleimani reportedly began micromanaging their military operations to an unprecedented degree. This shift, coupled with Soleimani’s strict command over the consolidated Iraqi, Afghani, and Pakistani Shiite militias fighting in Syria, highlighted the complex relations between Persian and Arab Shiites. Frequent appeals to sectarian identity had brought all Shiite militias under the IRGC flag during the course of the war, but this unity has since been challenged by deep-rooted Persian-Arab tensions. Those who have fought under Soleimani tend to remark on this tension; as one Hezbollah fighter told the author in December, “It was clear to many of us that [Soleimani’s] priority was to protect the Iranians, and that [Hezbollah fighters] and all non-Iranian Shiites could be sacrificed.”

Similarly, a number of other fighters have complained of being abandoned by their Iranian and Iraqi Shiite allies on the battlefield. Such incidents apparently led to many losses among Hezbollah’s ranks, and some fighters subsequently refused to fight under Iranian commanders. Likewise, many interviewees complained about the “stingy” and “arrogant” manner in which Iranians treat Arab fighters. As one fighter put it, “Sometimes I feel I’m fighting alongside strangers who do not care if I am dead…We should ask ourselves why we couldn’t accomplish anything in Syria, although we have advanced weapons, while the old Hezbollah generation achieved so much with more traditional weapons. We are fighting in the wrong land.”

Soleimani seems to have little tolerance for such criticism. According to one commander, “When complaints increased and the Hezbollah leadership stalled Soleimani’s requests to send more fighters to Aleppo, he cut salaries for three months, or until Hezbollah did what he asked.” Yet while most of the interviewees dislike him and his apparent disdain toward Arabs, they do respect and fear him, with the understanding that the relationship is now a boss-employee situation rather than a partnership. As a result, many veteran fighters have come to believe that the notion of a “unified Shiite identity” is a fiction, and they are returning home as disillusioned Lebanese Arabs rather than victorious pan-Shiite warriors.

THE NEW HEZBOLLAH FIGHTER?

Although Hezbollah’s leadership has sought to link the Syria war to grander goals — namely, the longstanding posture of “resistance” toward Israel, and the more recent call to defeat takfiri (heretical) Sunni Islamist groups such as the Islamic State — many fighters are unconvinced. They are cynical about this rhetoric because most of their battles have been aimed at propping up the Assad regime, not fighting the Islamic State. Many fighters also believe that they are paying all the costs while Iranians are reaping the benefits. As a result, significant numbers of veterans have been leaving Hezbollah, making room for a new and rather different crop of younger fighters.

According to some members who have taken leave from the war or quit entirely, the newcomers are not joining the fight for reasons of ideology or self-realization. They are there to collect a salary or secure their future — they are not particularly concerned about Hezbollah’s broader mission, and they tend to follow Iranian orders without complaining.

At the same time, however, the newcomers are apparently less loyal than their predecessors, and less well trained. According to Lebanese media reports, new fighters do not get more than a month or two of training before being thrown into battle. Previously, Hezbollah spent decades screening and preparing its fighters. The group’s leaders picked the creme-de-la-creme of young Shiites to join their ranks because they wanted loyal and trustworthy men. Today, Hezbollah’s army in Syria is full of unreliable young fighters who have no real moral compass.

REPERCUSSIONS IN LEBANON

The changes within Hezbollah’s fighting force are reflecting gravely on the Shiite community back home. Given the war’s general unpopularity and severe economic effects, Lebanese Shiites have become more isolated. They are also struggling to deal with returning fighters who often have a deleterious effect on their hometowns, whether by behaving aggressively, attempting to dictate local lifestyles, or generally instilling chaos. Government statistics are showing historically high rates of drug use, small crime, and unemployment, especially in the southern Beirut suburb of Dahiya, a Hezbollah stronghold. Even more disturbing is the absence of serious measures to counter these social problems. Lebanese authorities are not allowed to do anything in Dahiya without Hezbollah’s cooperation, but the group has seemingly done little to address the problems itself. In short, while many Shiites still view Hezbollah as their only protector and provider, they have not felt well protected or provided for in quite some time.

Hezbollah cannot keep absorbing these blows to its image for long, but Iran and Soleimani do not seem bothered by the situation, regarding it as Hezbollah’s problem. Whenever the group’s fighters leave Syria, they are immediately replaced by Iraqi Shiites who do not have the same domestic concerns about preserving the “resistance” against Israel. The fact that Tehran and Hezbollah sometimes differ in priorities and methods is hardly breaking news; among other past instances, Iranian leaders were less than thrilled about Hezbollah’s decision to launch a war with Israel in 2006. Likewise, Hezbollah fighters are not the only proxies that have chafed at Iranian arrogance; for example, captured Iraqi militants interrogated by U.S. authorities reportedly criticized their condescending Iranian trainers and advisors. Yet Iran’s Iraqi allies continue to soldier on in Syria even as Hezbollah veterans increasingly quit the field, so the current tensions should not be downplayed.

Several factors may help explain this trend — Hezbollah’s drastic rhetorical shift from “resisting Israel” to “fighting Sunnis,” the ever-worsening shortage of social services in Lebanon, the failure to achieve the promised “divine victory,” and the “bossy” attitude of the group’s supposed Iranian partners. Whatever the case, Hezbollah has lost some of its “sacredness” in Lebanon — for many Shiites, pursuing an alternative identity, narrative, or way of life is no longer viewed as futile.

One thing that could revive Shiite public support for Hezbollah at home is a confrontation with Israel. Although open war is not in the cards at the moment, post-Aleppo military operations in Syria have brought Hezbollah forces back to Lebanon’s borders, creating an opportunity for renewed anti-Israel rhetoric and provocations.

Alternatively, if Washington turns up the heat on Hezbollah amid increasing U.S.-Iranian tensions, the group may try to cast itself as a victim in order to regain public support. America’s interests would therefore be better served if its future actions against Hezbollah include a plan for exploiting the fissures and contradictions within the Shiite community (e.g., by creating economic and employment alternatives for potential recruits). Otherwise, Hezbollah will no doubt use any confrontation to bring the Shiites back to their sectarian base.

Hanin Ghaddar, a veteran Lebanese journalist and researcher, is the Friedmann Visiting Fellow at The Washington Institute.

The Washington Institute.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.