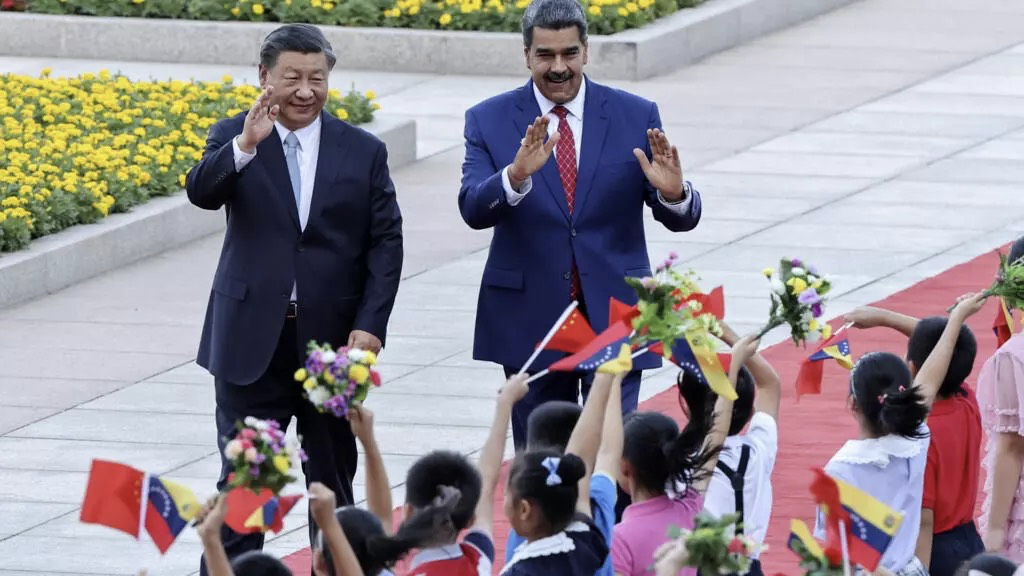

Chinese leader Xi Jinping with Venezuela’s then president Nicolas Maduro in Beijing in 2023. © Ding Lin, AP

The capture of Nicolas Maduro was, among other things, a way for Washington to reaffirm that Venezuela – and Latin America in general – fall under the US sphere of influence. The message may have been primarily directed at China, which will now find it more difficult to pursue its interests in the region.

The US decision to capture Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela decisively reaffirmed that Latin America lies within the US sphere of influence. “American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again,” US President Donald Trump told reporters shortly after the raid.

He underscored the point with a reference to the Monroe Doctrine, a 19th-century creed that put world powers of the time – notably European colonists – on notice to respect American hegemony in the region.

But the message may have been most pointedly directed at China, which for more than two decades has been developing close ties with Latin American countries – including billions invested in the Venezuelan oil sector.

Chinese war games in Latin America

The US raid came just days after China conducted two days of live-fire drills near Taiwan in a massive show of force. But a TV report broadcast in the week before Christmas hinted that China may also be weighing its military options in South America.

China’s CCTV state television aired a December 19 segment on wargames, simulated military engagements for training purposes. One scene depicted theoretical confrontations in Latin America, including simulated battles near Mexico, Cuba and the Caribbean Sea.

China currently has a minimal military presence in the region, which is far removed from Beijing’s traditional sphere of influence in Asia. But several observers wondered if these conflict scenarios signaled that its global ambitions are evolving.

Venezuela has historically served as China’s “gateway into Latin America”, says Amalendu Misra, a specialist in international relations and the Global South at Lancaster University. With Maduro’s ouster, Beijing has lost its key ally in the Latin American country where it has invested the most, which Misra says came as a “shockwave” to Beijing.

China has loaned more than $100 billion to Venezuela since the early 2000s. “That’s nearly 39% of all the loans Beijing allocated to the region,” Misra points out.

Former Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez lauded the deals he made with China back in 2006, describing them as a “Great Wall” against US hegemony in the region.

A mountain of unpaid debt

The close relations between Beijing and Caracas persisted even after Chavez’s death in 2013. One of the last people Maduro saw, just hours before being ousted by US forces, was none other than China’s special envoy to Venezuela, Qiu Xiaoqi, who was on a visit to reaffirm the strength of ties between the two countries.

The fate of their $100 billion Venezuelan investment must now be worrying Chinese leaders, although a large portion of the debt has already been repaid in raw materials. China’s dealings with Venezuela are modeled on the “Angola system” – that is, countries receive funding and are repaid in commodities but namely oil, says Mario Esteban, director of the Centre for East Asian Studies at the Autonomous University of Madrid.

While precise figures are not publicly available, the Belgian think tank Beyond Horizon estimates that Caracas still owed Beijing more than $12 billion as of December.

As the United States looks to capitalize on – and possibly even administer – Venezuela’s vast oil resources, it may find itself negotiating with China.

Beijing will need to have “a seat at the table” when decisions are being made about how and when to repay Venezuela’s creditors, says Günther Maihold, a Latin America specialist at the Free University of Berlin.

Trump has said that American oil companies will be able to continue selling Venezuelan oil – including to China – once they have rebuilt the country’s oil sector. But Beijing may not agree to this arrangement, says Carlotta Rinaudo, a China specialist at the International Team for the Study of Security Verona. “I wouldn’t be so sure, to be honest, that China would buy oil sold by US oil giants,” she says.

Beijing also had its sights set on other resources: Venezuela possesses the world’s largest untapped reserves of gold as well as oil. The China National Petroleum Corporation, for example, had already established several joint ventures with local companies to explore Venezuela’s subsoil.

Sino-Venezuelan cooperation on vast infrastructure projects has also led to some 400,000 Chinese to settle in Venezuela, working primarily in the restaurant sector.

From the Chinese perspective, Rinaudo says, a longtime partner is now essentially defunct. And after investing so much, “they cannot afford to lose all that money”.

Limited room for manoeuvre

The United States is unlikely to want to share Venezuelan resources with rival China, which Rinaudo says may create a new source of competition – and friction – between the two countries.

Beijing has reason to be wary. The US operation in Venezuela represents a newly aggressive version of the Monroe Doctrine adapted to the Trump era – namely, the desire to rid Latin America of all other foreign influences. Secretary of State Marco Rubio stated as much after Maduro’s ouster, saying the United States would not allow the oil industry in Venezuela to be controlled by “adversaries”, namely Russia, China or Iran.

“This is the Western Hemisphere. This is where we live. And we’re not going to allow the Western Hemisphere to be a base of operations for adversaries, competitors, and rivals of the United States, simple as that,” he said.

And Esteban is not convinced that China’s recent wargaming indicates any kind of real shift in global focus, saying it is unlikely that Beijing would be willing to commit troops to a theatre so far away. He says the CCTV report was primarily aimed at a domestic audience, to demonstrate that China thinks like a global military power.

But Venezuela might just be the first of China’s headaches in Latin America, with the United States already exerting pressure on Colombia and Cuba as well as Mexico.

This pressure could be one way “to discourage them from doing business with China”, notes Esteban.

While Colombia and Cuba are not economically important to Beijing, Mexico is a different story: Beijing has already invested heavily in Mexican supply chains as well as its transport infrastructure.

“All the ports are owned by the Chinese. Most of the roads are owned by the Chinese,” Misra says.

The automobile industry gets a lot of its supplies from China, especially for cars and trucks, which are then mainly exported to the United States, Maihold adds.

Realistically, China has limited options for protecting its interests in the region. By removing Maduro, Washington also managed to signal to other Latin American powers that China cannot protect them if they choose Beijing over Washington.

On the ground, Maduro’s capture was a failure of Chinese intelligence, Rinaudo says, noting that China “had no idea” of the US plans.

But it was also a failure of matériel, with Beijing’s air-defence system proving ineffective. “Its missile system didn’t work. All the radars that the Chinese had installed are in Venezuela – didn’t work,” Misra says.

If China were to respond to US actions aggressively, Esteban predicts that cyber-attacks would be the weapon of choice. But he says the most likely scenario is that Beijing will launch a vast diplomatic charm offensive in the region.

It would be easy to play on bitter memories of past US actions in Latin America by “emphasizing sovereignty, emphasizing the UN charter – emphasising these core principles” of international law, Esteban says.

“They know their history … and there is a very long history of US intervention.”

FRANCE24/ AFP