File :Evidence has been uncovered in Syria that implicates President Bashar al-Assad and members of his entourage, in war crimes and crimes against humanity, UN human rights chief Navi Pillay said on Dec 2, 2013

A month after Bashar al-Assad’s regime collapsed, Syria’s Alawite minority, which served as the regime’s backbone, fears a witch hunt. In their stronghold of Tartus, members of the community recount that they too suffered under the former dictator’s bloody tyranny.

On his face, a black eye. On his back, large bruises. Ali*, a young man in his early twenties, is terrified. The former Syrian soldier claims he was stopped a few days ago at a checkpoint near the village of Khirbet al-Ma’zah, close to the Mediterranean coastal city of Tartus.

“They told me, ‘You’re an Alawite pig!’ They treated me like an animal because I’m Alawite,” he said, speaking under the condition of anonymity for safety reasons.

In a secluded location away from prying eyes, Ali recounted being dragged off a bus by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, formerly linked to al Qaeda) militants while on his way to seek the promised amnesty for ex-regime soldiers who had not committed acts of bloodshed or torture. Taken to a checkpoint along with seven others, he described being tied up, detained and beaten with fists, feet and iron bars. He endured five hours of torment before being dumped on the roadside.

“I didn’t want to be in Bashar’s army, but I had no choice. We were poor and they would have arrested my family,” he said, insisting he had never committed violence. “I don’t leave home anymore, especially after sunset. The masked men terrify us. I’m sure they’ll punish the entire [Alawite] community.” He referred to HTS checkpoint guards, most of whom wear masks or scarves that cover everything but their eyes.

‘A climate of fear’

The city’s new Islamist rulers dismissed the claims. “There may be isolated incidents at checkpoints, but these are rare,” said Rahim Abu Mahmoud, an HTS official overseeing soldier reintegration in Tartus. “We make no distinctions between communities and our relations are good with everyone. Our issue is with those who have not regularised their status or hidden weapons. Others have nothing to be scared of. The issue is that a climate of fear has been fuelled by the spread of fake videos.”

Reports of insults, harassment, punitive raids, disappearances and murders have proliferated on social media since Assad’s fall. Videos allegedly showing HTS fighters humiliating, beating, or inciting violence against Alawites circulate without verification. While the UN works to corroborate such footage to prevent escalating sectarian violence, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights estimates that around 150 Alawites have been killed over the past month.

In Tartus, the Alawite stronghold, paranoia has taken hold. During the Assad dynasty’s 50-year rule, Alawites formed the regime’s backbone, with about 80% working for the state, many in intelligence, security, or the military. Their community make up about 10% of the general population and is often referred to as an offshoot of Shia Islam.

Now, many Alawites insist they too were victims of the regime. “In 2000, my father left the army because he couldn’t stand the corruption among senior officers,” said Hasan*, a 21-year-old engineer. “They even stole food meant for soldiers! His salary was only $25, but he had no choice.”

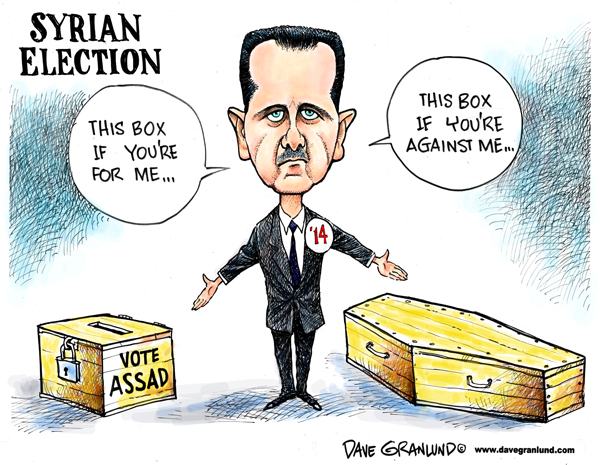

Assad and the ‘divide and conquer’ doctrine

Bashar al-Assad consistently portrayed himself as a protector of religious minorities, a rhetoric that intensified in 2011 with the rise of the Islamic State group and al-Nusra Front (founded by Ahmed al-Sharaa, better known by his nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, now Syria’s new strongman).

“We were all Syrians, but when the revolution began, everything changed,” Hasan said. “It started as a peaceful movement against Bashar. Then [Islamist rebels] began killing Alawites simply because they belonged to the same community as Assad,” he lamented, recalling relatives killed in Homs. “Assad did everything to amplify that divide. It was divide and conquer.”

When the regime fell, the euphoria was short-lived, Hasan said. “I always hated him, but I was scared. The population supported Bashar until three or four years ago,” he added, referring to pro-Assad demonstrations in Sunni and Christian areas like Aleppo and Homs. “We were all scared because everything was dangerous. Just saying the word ‘dollar’ could land you in prison.”

That fear has not disappeared under HTS rule. Despite unity messages from Syria’s new leader, Hasan, like many of his co-religionists, fears a “fitna”, a term for sectarian strife.

“Only 10% of Alawites were corrupt, but they ruined life for the other 90%,” he said. “They harassed us too. If you had a foreign bank transfer, they’d freeze your account to take the money. Three years ago, I started using cryptocurrencies to work with American or European clients.”

‘Hitler hated Jews, Assad hated everyone’

Ammar*, a young doctor, remains deeply anxious. “I don’t feel like a citizen,” he said. “I don’t have the right to be happy. We’re labelled as heretics (Alawism being a distant offshoot of Shiism). We’ve all been branded as pro-Assad. Many massacres he committed were portrayed as Alawites killing Sunnis. Now, they want to kill us.”

Ammar deliberately failed his medical exams for three years to avoid military service. In Syria, graduates had to serve at least two years, often far longer. “You go in not knowing when you’ll come out. Some stayed for ten years,” he said. “We missed out on our youth. I feel like an old man trapped in a young body.”

Ammar is convinced that those he once considered brothers will seek vengeance for the dictator’s crimes. “If I stay here, I’ll never be able to support my family or start one. It’s not only an economic threat but an existential one,” he said. “Last week, I had to leave the governorate. I made sure my phone could livestream if anything happened to me. If I’m killed, I don’t want to be labelled pro-Assad. Call me an Alawite thug, but don’t call me pro-Assad. I’m not.”

Ammar does not mince his words. Speaking calmly, he draws grim historical parallels to describe the “sadistic” Syrian tyrant. “Hitler hated Jews. Assad hated everyone. Stalin acted in the Soviet Union’s interest, but Assad didn’t care about Syria. He built a farm where we all worked to enrich him. He ensured that when he left, only hatred would remain.”

The young doctor refuses to be a scapegoat. “Many regime war criminals were Sunnis: Ali Mamlouk, the intelligence chief; Asma, Bashar’s wife; Moustapha Tlass, the former defence minister … Bashar al-Assad behaved like a monster not because he was Alawite but because he was a monster.”

In the seaside town of Tartus, people are beginning to speak out. Razan*, a civil servant, already feels she has paid a heavy price. “My husband died because of Bashar al-Assad. He was serving in the army and was killed by extremist groups in Latakia in 2016. At his funeral, my son tore down the portrait of Bashar that was hanging up,” she said tearfully, adding that her daughter never knew her father. “I’ve never had the slightest compensation.”

Razan quickly regains composure before voicing her fear of retribution. “When HTS entered Tartus, I destroyed my husband’s photo. I was terrified they’d find it. He’s a martyr and they have their martyrs. I’m willing to forgive them for spilling his blood if they guarantee the safety of my two sons, who fled abroad to avoid conscription.”

‘I’m Syrian above all’

While resentment towards the Alawites had always existed under the Assads, 13 years of war transformed it into hatred. For Hassan G. Ahmad, who insists on using his real name, this shift has been a double burden. “The hatred of this regime was not directed at any particular community. It was inflicted on anyone who opposed it, regardless of their religious or political affiliation,” the 26-year-old said. “We must not forget that some Alawites participated in military operations against the Syrian regime. The Alawite opposition had chosen the political struggle, like Dr Abdel Aziz from Assad’s home town. He has been detained for more than 12 years and we still don’t know his fate.”

The activist, who endured repeated imprisonment and torture between 2023 and 2024, added, “The Alawites arrested for political reasons were tortured far more than the others. They were considered traitors.” As he talked, he mimed with a smile the tortures inflicted on him. “I still have nightmares about it, but I find solace in dark humour.”

The Alawites have been “in the grip of an anxiety crisis since December 8 (the date marking the fall of Assad’s regime),” he continued, rejecting the term “minority”. “We need a government that includes all parts of society. Right now, it’s monochromatic. I’m not Muslim, Alawite, atheist, Sunni, or anything else. I’m Syrian, above all.”

FRANCE24