Photo: Thousands of people have fled areas of fighting between the opposition and the government forces

The speed with which the status quo in Syria – however unresolved and unsatisfactory – has been turned on its head in recent days has been extraordinary.

Syrian government officials and supporters were still asserting the army would hold the line at Hama, even as insurgent fighters were entering the city.

Shortly afterward, the Syrian military acknowledged that it had pulled out of Hama, ceding control of the city for the first time to rebel factions.

After capturing two major cities within a week, the next target for the insurgents led by the Islamist group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), is Homs.

Tens of thousands of people are fleeing the city in anticipation of what looks likely to be the next major battle.

The stakes have risen precipitously for President Bashar al-Assad and his key backers, Russia and Iran.

Homs is strategically considerably more significant than either Aleppo or Hama. It straddles a crossroads that leads west to the heartland of support for the Assad dynasty and south towards the capital, Damascus.

Whatever the previous strategy of HTS may have been, as it spent years building its power base in the north-western province of Idlib, the momentum of the past week now seems to be leading inexorably toward a direct challenge to the continuing rule of Assad.

In an interview with CNN, HTS leader Abu Mohammed al-Jawlani confirmed the rebels do indeed aim to overthrow the Assad regime

So, attention is now focusing on whether the Syrian leader has the capacity to see off this renewed attempt to topple him from power.

The Syrian army – which is largely made up of conscripts – might have lost the war years ago if outside forces had not come to Assad’s aid.

Soldiers are underpaid, under-equipped, and often have poor morale, with desertion having long been an issue.

As his military failed to hold Aleppo and then Hama, Assad issued an order raising soldiers’ salaries by 50% – but that in itself is unlikely to turn the tide.

Russian planes backed up Syrian forces in Hama, but clearly not strongly enough to make an impact.

The lack of all out Russian military support has fuelled speculation that Moscow may be less able to play the game-changing role that it performed in Syria in 2015. That would be down to almost three years of war in Ukraine, draining its reserves of manpower and military hardware.

But Russia still has compelling reasons to stay the course with Assad. President Putin’s decisive, full-scale military intervention, which kept the Syrian leader in power when he was close to defeat, exposed the failure of Western allies -former US president Barak Obama in particular – to honor the promises of support to the rebels.

Former US President Barack Obama ran out of red ink as he continued to threaten the Syrian dictator over crossing his red lines. His hesitation in taking any decision in support of the rebels is considered one of the main reasons Assad is still in power.

The naval base that Russia has maintained for decades in the Syrian port of Tartus gives Moscow its only military hub in the Mediterranean. If the insurgents can take Homs, that could potentially open up a route toward the Syrian coast that could put the base at risk.

It still seems unlikely that Russia would not feel a political and strategic imperative to refocus its firepower on the rebels to keep Assad in power, even if only in control of a diminished rump of Syria drastically shrunk from the 60% he currently controls.

The other big question mark is over Iran and the militias it has backed – including Hezbollah- and the military expertise it has provided, which have been the other key element in keeping Assad in power.

Hezbollah leader Naim Qassem – who took over after Israel’s assassination of Hassan Nasrallah – has declared that the group will stand by the Syrian government, against what he has described as jihadist aggression orchestrated by the US and Israel.

But with its leadership decimated and its fighters still regrouping after Israel’s ground and air offensive against the group in Lebanon in recent months, Hezbollah may be nowhere near the strength it had when it battled on the frontline against Syrian rebel factions.

However, it clearly is still committed to playing its part, with security sources in Lebanon and Syria saying that elite forces from Hezbollah have crossed over into Syria and taken up positions in Homs.

As for Tehran, it currently seems to be edging away from both direct and proxy confrontations in the region, in contrast to its far more aggressive strategy in the past few years.

That may limit its appetite for the kind of full-scale military support for Assad that it has provided in the past.

There has been speculation that Iranian-backed militias in Iraq may enter the fray – but both the Iraqi government and one of the most powerful Shia leaders, Moqtada al-Sadr, have warned against this.

Assad’s chances of political survival will depend not only on the capabilities of his armed forces and his key allies but also on the relations between the various groups that oppose him.

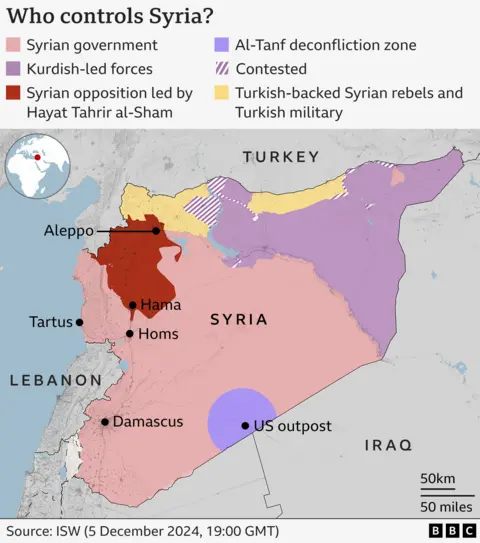

Beyond HTS and the factions from Idlib, there are the Kurdish-led forces in the north-east, the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army in the north, and a host of other groups that still have some purchase in various regions of the country.

Among them is the Islamic State (IS) group, which could take advantage of the latest conflict to try to make gains beyond the remote desert regions where it still has a toehold.

The failure of rebel factions to unite was one of the key factors in Assad’s political survival. He and his supporters will be hoping that events play out in the same way again.

For now, support for the Syrian president as the least worst alternative still seems to be held among several minority groups – including of course the Assads’ own minority Alawite sect.

They fear what they view as a jihadist force taking over their towns and cities. HTS may have renounced its previous affiliation with al-Qaeda, but many still see it as an extremist organization.

In the end, what Assad’s fate seems most likely to hinge on is what the main outside players in Syria decide.

Russia, Iran, and Turkey have come to agreements before over conflict zones in Syria, most notably in Idlib four years ago – but the rapid surprise escalation in Syria may have blindsided them all.

They may all soon have to reassess and come to a decision on what suits their interests – a Syria with Assad or without.