KFAR SHOUBA, Lebanon — Every summer, the Lebanese brace for war. Border skirmishes and rocket exchanges with Israel have become almost commonplace throughout the year. But since the 2006 July War, fears of a serious escalation intensify as the months grow hotter.

In Lebanon’s deep south, along its disputed border with Israel, this apprehension is especially sharp. Residents feel they are at the mercy of events beyond their control, including provocations by Hezbollah and clashes inside Israel, fearing they could soon lead to violence in their own backyard. They find stability in the instability, they say, comforting themselves with the belief that a full-blown war is too costly for either side.

War “doesn’t leave our minds,” said Ahmed Deeb, the mayor of al-Wazzani, a village of 400 that has seen its population dwindle over the decades after each cross-border conflict. “Because the decision isn’t in our hands.”

In early May, a tent appeared more than 100 feet south of the Blue Line, the contentious border monitored by the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon, or UNIFIL. U.N. forces observed individuals repeatedly crossing from Lebanon into the contested area; closed circuit TV cameras were installed next to the tent on May 30. By June 17, a second tent was spotted, and UNIFIL asked the Lebanese army to remove them.

One was taken down, the other stayed. Hezbollah, the Iran-backed militant group and political party, claimed responsibility for the tents. In a speech marking the 17th anniversary of the July War, leader Hassan Nasrallah said they were erected in response to a move by Israel last year to cordon off parts of the village of Ghajar.

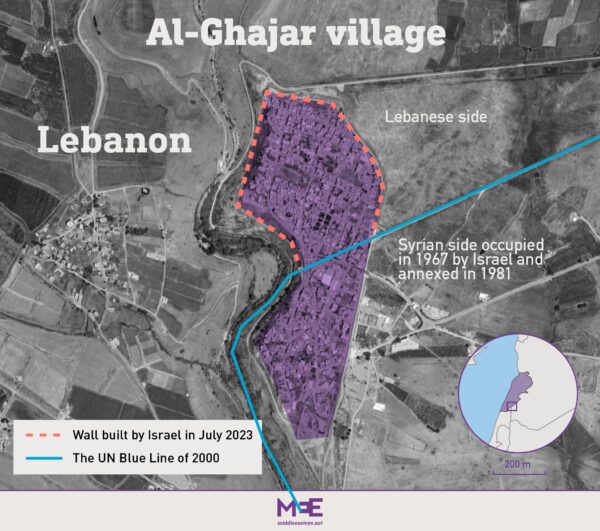

Ghajar is a microcosm of the region’s intractable border issues. The southern half of the village lies in the Golan Heights, the disputed territory annexed by Israel from Syria in 1967. When southern Lebanon was under Israeli occupation, the village expanded north into Lebanese land. After the Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000, the Blue Line bisected the village, placing the northern part in Lebanese territory.

Israeli forces then retook the northern part of the village during the 34-day war between Israel and Hezbollah in 2006. They were meant to withdraw under the terms of the U.N. Security Council resolution that ended the conflict but never did.

Northern Ghajar is now a swath of Lebanese land, populated by Syrians carrying Israeli passports.

Despite calls by UNIFIL, the Lebanese government and Hezbollah for Israel to leave, its forces have only solidified their presence over the past year, reinforcing a wall hugging Ghajar’s northern perimeter.

In his televised speech, Nasrallah said Israel was trying to turn the area into a tourist spot and accused the United Nations of a double standard. “The Israeli occupation erected a barbed fence around the Lebanese Ghajar village … and the international community was silent on all Israeli transgressions but moved fast after [Hezbollah] erected a tent at the border,” he said.

Since then, there have been a succession of tense incidents. On June 8, an Israeli bulldozer drove north across the withdrawal line to dig trenches in the village of Kfar Shouba, located near the disputed territory called Shebaa Farms.

A Lebanese villager, Ismail Nasser, stood in the digger’s way and refused to budge. A video showed the 58-year-old standing nonchalantly with his hands in his pockets, his head turned sideways to look at the machine pushing dirt on him. As the earth submerges his legs, he picks up a rock and lobs it at the looming bulldozer.

The video, evoking images of rock-throwing Palestinians, went viral across the Arab world.

“I felt as if there were 500 people grasping onto my legs and not letting go, as if it wasn’t even my own will,” said Nasser, a retired army officer. “It was as if you super-glued my feet to the ground.”

Nasser said that before the video was taken, the bulldozer had retreated and changed routes half a dozen times to bypass him. He believed that killing a Lebanese citizen on Lebanese land, albeit disputed, would warrant a response. The thought emboldened him.

“We suffer constantly, daily,” he said in an interview in his house last week. His mother lost her eye to a mine explosion in 1975. His father and brother were both imprisoned by the Israelis. Ten goats died during a bombardment in 2004; one of his shepherds was killed in 2008.

Nasser blames all sides for the disarray in the south: Israel, Hezbollah and the notoriously ineffectual Lebanese government. But he thinks a real war is “impossible.”

“America doesn’t have time to support Israel [in such a war], and Russia doesn’t have time to support Lebanon,” he said. “And Arab countries also don’t want to have to rebuild Lebanon. So we are in a state of stable lack of calm. We are stable, but anxious.”

Local anxiety deepened July 6, when rockets were launched from southern Lebanon by suspected Palestinian militants following Israel’s largest military operation in the West Bank in decades. Israeli responded with retaliatory strikes. There were no deaths on either side.

Then, on July 12, the anniversary of the July War, several members of Hezbollah were injured when the Israeli military used a “nonlethal weapon” to push back suspects it said were attempting to damage a security fence.

Israel has since increased its military presence on the border, even as it is rocked by protests at home over a contentious plan to weaken the Supreme Court. Israeli army officials have repeatedly warned Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, his security cabinet and their American counterparts that Hezbollah is preparing to take advantage of its internal crisis and launch an offensive, according to local news reports.

With thousands of Israeli reservists threatening to boycott their training to protest the judicial push, Israel Defense Forces chief of staff Herzi Halevi issued a rare statement last week, warning that a weakened Israeli military would imperil the country’s existence.

In October, Israel and Lebanon agreed to a U.S.-brokered deal demarcating their maritime borders, hailed by diplomats as a historic breakthrough. Many hoped the resolution of land borders would follow.

The Lebanese and Israelis hold a UNIFIL-chaired meeting every five to six weeks to discuss military issues, including violations along the Blue Line. The meetings require a delicate dance: No media is allowed; the food is provided by the Italian UNIFIL contingent, including Italian bottled water, to avoid friction over which local cuisine should be served; the generals do not shake hands.

UNIFIL spokesman Andrea Tenenti described the scene: “Just two sides sitting in a very small room, on very uncomfortable chairs on purpose to just keep the focus very military.”

Tenenti emphasized the need for separate meetings that specifically focus on demarcating the Blue Line. The Lebanese have 13 points of dispute along the border; the Israelis have an unannounced number. A sticking point, said Tenenti, is agreeing on a geographical point to begin the negotiations.

“Both sides are in a way keen to solve the contentious issues. But everyone wants to solve it in their own way,” Tenenti said.

The continued meetings and 17 years of relative stability are, to Tenenti, a sign that neither side has “an appetite for a conflict.” But he conceded it is always a fragile calm.

“There’s been a lot of increasing tensions,” he said, “but nothing has changed.”

Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.